In the world of archives, most discoveries arrive quietly.

A box is opened. Tissue paper is lifted. A photograph is held up to the light. The past shows itself the way it always does: ordinary, faded, and seemingly settled.

Dr. Sarah Chen had spent nearly a decade doing this kind of work. Her research focused on the slow, painful evolution of child welfare reform in America, the era when laws were inconsistent, authority was rarely questioned, and the suffering of children could be hidden behind polite language and respectable appearances.

She had read thousands of pages that made most people look away. Court transcripts. Institutional reports. Letters from reformers arguing for change. Diaries from people who witnessed harm and didn’t know how to stop it. Over time, she had learned a difficult balance: to study the evidence with discipline, without losing the human reality behind every line.

But one photograph in the Massachusetts Historical Society unsettled her in a way that documents never had.

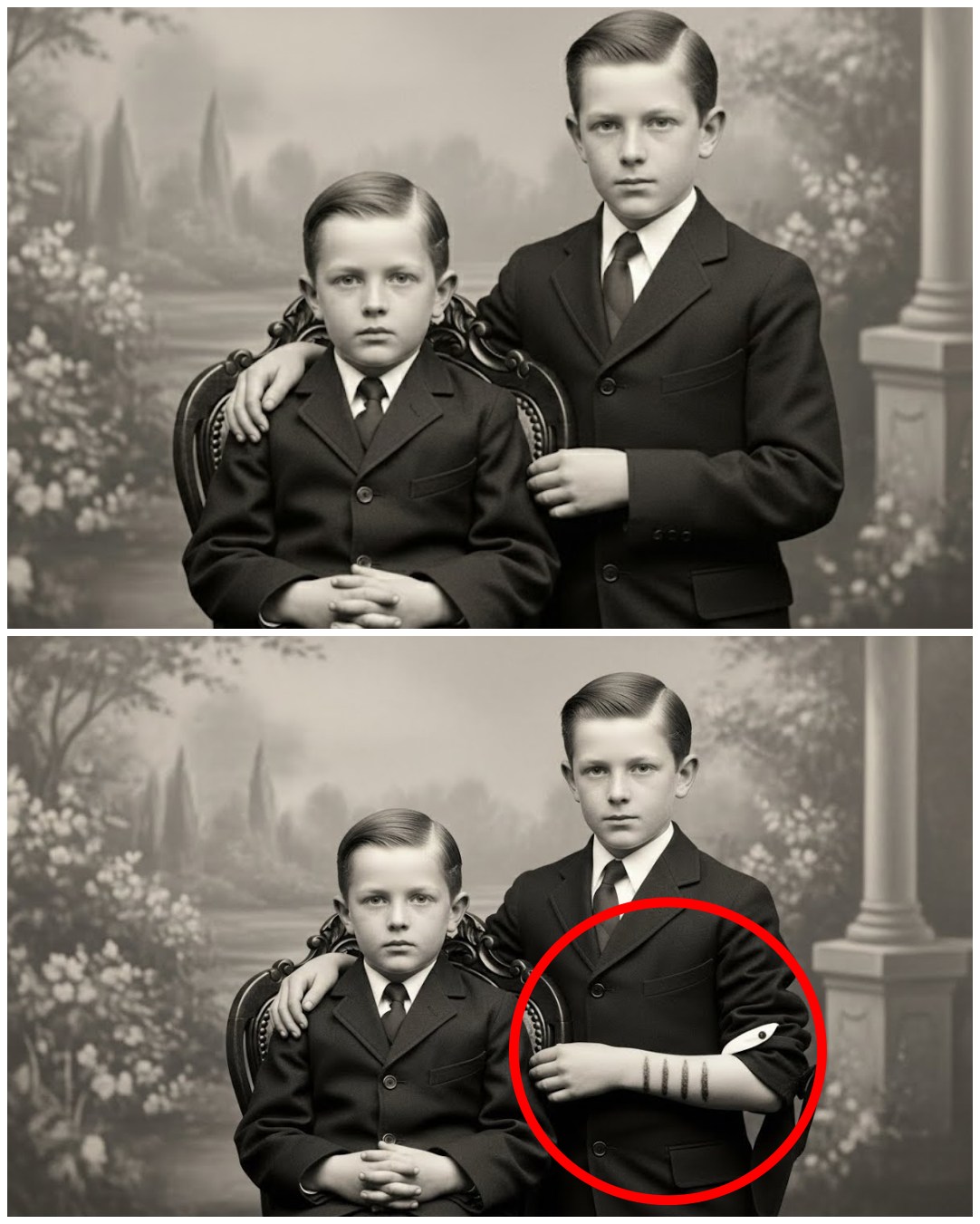

It was a studio portrait dated March 1889, taken in Worcester, Massachusetts, by a photographer named J.H. Morrison. The boys were labeled simply: Thomas and William, “the Hartley boys.”

At first glance, it looked like a typical middle-class portrait from the late nineteenth century.

A painted garden backdrop. A carved chair chosen to keep a seated subject steady during a long exposure. A small side table with artificial flowers meant to soften the scene and suggest gentility. Everything about it spoke the language of respectability.

The younger boy sat in the chair, hands folded carefully in his lap. He wore a dark suit that looked newly pressed, hair neatly parted, posture stiff with the effort of staying perfectly still. His expression carried that familiar mixture of seriousness and uncertainty children often wore when they were told, “Don’t move.”

The older boy stood beside him, slightly behind the chair, one hand placed on his brother’s shoulder. It was a standard pose, the kind studios recommended: older sibling as guardian, younger sibling as the one being protected. Yet something about the older boy’s eyes caught Sarah’s attention immediately.

He looked tired.

Not the tiredness of a long day playing outside, but a heavier fatigue that didn’t belong on a child’s face. His gaze met the camera directly, but without the soft confidence of a boy who felt safe. There was tension in his posture, too—an alertness that seemed less like nervousness in front of a camera and more like a practiced readiness for the next moment to go wrong.

Sarah wrote her initial notes and moved on. She had dozens of items to review that afternoon.

And still, the older boy’s expression followed her.

The next day she returned to the image, telling herself she was being overly sensitive. Historians can project meaning onto anything if they stare long enough. Yet the feeling remained. The portrait didn’t read like a family celebrating itself. It read like a family performing itself.

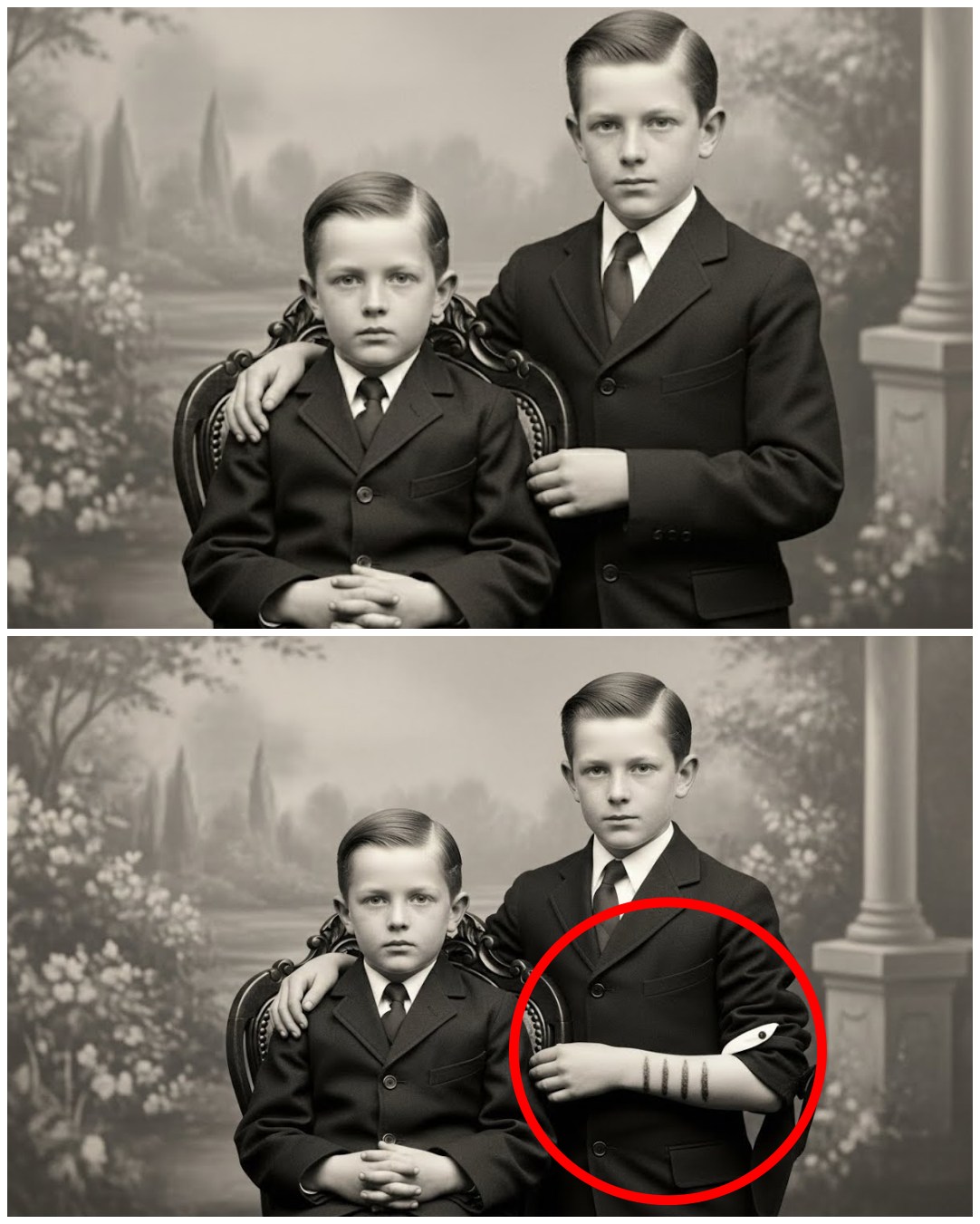

On her third look, she brought a magnifying glass.

She examined the suit fabric, the stitching, the way the older boy’s sleeve sat near his wrist. The sleeve seemed slightly pulled back, as if the photographer had adjusted his arm into position and the cloth had shifted a little during the process.

That small shift was enough.

Just above the older boy’s wrist, partially exposed by the lifted sleeve, were four parallel bands across the skin—faint, but too regular to be random. They ran horizontally, evenly spaced, like marks that had faded over time but had once been sharply defined.

Sarah’s chest tightened.

She had seen this pattern before in historical evidence, described in reports and testimony. The shape was not consistent with everyday bumps or play injuries. It suggested repeated, deliberate force applied in a consistent way—harm that left a lasting record on the body.

The most unsettling part wasn’t only that the marks existed.

It was that the boys had been dressed in their best clothes, taken to a studio, positioned under a painted garden backdrop, and photographed as though their lives were entirely normal.

A public image of comfort, with a private truth peeking through because a sleeve had slipped by an inch.

Sarah sat back and stared at the portrait until the room felt too quiet.

In her work, she often confronted the gap between how families appeared and what children lived through. But this was different. A photograph made to communicate stability had preserved evidence that stability was, at best, incomplete.

She began searching for the Hartleys.

The name was common enough to scatter across records, but Worcester was manageable. Sarah pulled census documents, property listings, church directories, and death records. After several days of sorting, she found a household that matched the photograph.

In the 1880 census, Ezekiel Hartley was listed as the head of household, a manufacturer living on Elm Street with his wife Martha and two sons: Thomas and William.

The ages lined up. Thomas would have been about twelve in 1889. William would have been around ten—close enough to Sarah’s visual estimate, especially given how portraits sometimes made children look slightly older or younger than they were.

Then Sarah noticed a detail that changed the shape of the story.

Martha was identified as Ezekiel’s second wife.

That meant Thomas had likely been born to a first marriage. A search confirmed it: Ezekiel’s first wife, Caroline, had died in 1878, when Thomas was still very young. Ezekiel remarried quickly. William, the younger boy, was born after that marriage—Martha’s biological child.

Sarah did not want to jump to conclusions. History is full of stepfamilies that were loving and stable. Yet she couldn’t ignore the uncomfortable pattern that appeared again and again in child welfare records of that era: blended households where one child became a target while another was protected.

She kept digging, hoping for clarity either way.

What she found on the surface was respectability.

Property records suggested the Hartleys were comfortable. Church logs placed them among active members of their congregation. Ezekiel’s business appeared legitimate and steady. Their names appeared where names appear when people want to be seen as decent: donor lists, committees, civic mentions.

Nothing indicated crisis.

Nothing indicated intervention.

And then, in 1891, Ezekiel Hartley died, leaving Martha as the only parent in the home.

Sarah traced the boys forward in records. William’s life remained visible: schooling, later business involvement, marriage notices in local circles, a steady presence. Thomas, however, faded.

He appeared in school enrollment through the early 1890s.

Then he disappeared.

When Sarah reached this point, she moved beyond public records and into institutional archives. In that era, when a teenager had nowhere to go, there were places he could end up—homes for boys, apprenticeships arranged through charities, reform institutions that claimed to correct “wayward youth.”

It was in those records that Thomas reappeared.

In September 1893, a sixteen-year-old named Thomas Hartley was admitted to the Worcester Boys’ Home. A local minister had brought him in after finding him sleeping rough in an industrial area. The intake notes described him as intelligent, quiet, reluctant to discuss his family. The minister noted that the boy showed evidence of long-term harsh punishment.

The Boys’ Home contacted Martha Hartley.

Her response was brief, cold, and final: Thomas was “incorrigible,” and she would not take responsibility for him.

The institution did not send him back.

In the months that followed, staff notes described Thomas as cooperative but distant, a boy who followed rules yet avoided closeness. Medical examinations documented old scarring on multiple areas of his body, consistent with long-term harm rather than one isolated incident. The physician recommended that Thomas not return to his former household.

At eighteen, Thomas aged out of the Boys’ Home. The final entry stated that he was placed in an apprenticeship with a printing firm in Boston. Far enough away to start over. Far enough away to become hard to trace.

Sarah followed him there.

Boston directories listed him first as a printer’s assistant, then as a typesetter. He married a woman named Agnes Sullivan. They had children. His life began to look like a quiet rebuilding.

Then, in 1909, Thomas made a decision that told Sarah everything about what he wanted to carry—and what he refused to carry.

Court records showed a legal name change.

Thomas Hartley became Thomas Sullivan, taking his wife’s surname and severing his formal link to Worcester.

His petition was short but direct. He wrote that he wished to leave behind a childhood associated with cruelty and suffering and to build a life unburdened by the past.

The judge approved it without demanding details.

Thomas Sullivan lived into old age. His obituary mentioned his career, his family, his community. It did not mention Worcester. It did not mention the Hartleys. It did not mention the brother in the 1889 portrait.

He had erased his first sixteen years from the public record.

But the photograph had survived.

The question that haunted Sarah then was simple: who saved it?

It seemed unlikely that someone responsible for harm would preserve a portrait that risked revealing it. Yet the image existed in an archive, carefully labeled and protected, waiting for someone to look closely enough.

Sarah searched for descendants of Thomas Sullivan and found a granddaughter, Margaret Sullivan O’Brien, living outside Boston. Sarah wrote cautiously, explaining her discovery and asking whether the family knew anything about Thomas’s early life.

Margaret replied with a surprising honesty.

Yes, she wrote, her grandfather had told her some of it. Not every detail, but enough to explain why he changed his name and why Worcester was never spoken of. He had described a home where he was treated differently, where harsh punishment was frequent, where he learned early that silence was safer than protest.

But he had also spoken of William.

Grandfather said William wasn’t cruel, Margaret wrote. He was just a child, too. Sometimes he tried to help in small ways. Sometimes he looked scared. Sometimes he didn’t understand. Grandfather never blamed him.

The hardest part of leaving, Margaret wrote, was knowing William would think he’d been abandoned.

And then she added something that made Sarah pause.

Margaret said her grandfather had kept a studio portrait all his life: two boys, dated 1889, labeled Thomas and William.

When Sarah received the scan, she compared it to the archive photograph.

They were the same.

Two copies of a single portrait, preserved separately for decades, both carrying the same tiny, devastating detail: the marks beneath the older boy’s shifted sleeve.

If Thomas had kept the photograph, he kept it for William—the brother he couldn’t bring with him.

What Sarah learned later added another layer.

After William Hartley died in 1947, papers donated to a local historical society included an unsent letter addressed to Thomas at an old Boston address. It was dated 1902, years after Thomas had left Worcester.

In it, William wrote that he was sorry. He wrote that he understood more now than he did as a child. He wrote that he knew Thomas had endured a kind of suffering William had been spared. He wrote that he did not expect forgiveness. He only wanted Thomas to know he had not forgotten him.

And he mentioned the portrait.

He wrote that he kept it, too.

But the letter was never sent. By the time William wrote it, Thomas was already disappearing into a different identity.

Two brothers. Two copies of the same photograph. Two lives shaped by the same household in different ways. Both carrying, in silence, what they couldn’t say out loud.

When Sarah finally published her research, she didn’t present it as a mystery meant to entertain. She presented it as a case study in what the nineteenth century often did to children: demanded obedience, prioritized appearances, and treated family authority as nearly untouchable.

The portrait became an example she used when teaching students how history hides in plain sight.

Not through sensational secrets.

Through small things.

A sleeve that slips.

A mark that shouldn’t be there.

A child’s eyes that look too old.

And the unsettling truth that sometimes the past wasn’t hidden at all.

It was simply politely ignored, until someone in the future chose to look closely enough to see it.