German Soldiers Dismissed the Apache Scout — By Morning, a Whole Patrol Was Missing

October 1944. The Hürtgen Forest.

The first time the German patrol heard about him, they didn’t take it seriously.

An Apache scout, they were told. Light on gear. Quiet. Unusual methods. No heavy kit. No dramatic reputation in their eyes—just a rumor drifting through the wet woods.

And then, by dawn, twelve men from a hardened unit had slipped out of reach—no confirmed firefight, no clear engagement, no clean explanation that fit the usual rules of patrol work.

This is a story about terrain, patience, and the kind of knowledge that isn’t learned in manuals. It’s about what happens when one side believes the forest is just “ground to cross,” and the other side treats it like a living map.

The fog that morning lay low and stubborn, wrapping trunks and branches in a gray veil. Sergeant William Cartwright stood outside the command tent, watching Captain Robert Harrison speak to the new arrivals. Two Native American soldiers waited at the edge of the group.

One looked slightly uncomfortable in the uniform—as if he wore it because duty required it, not because it shaped his identity. The other carried himself differently, as if he belonged to the woods first and the Army second.

Cartwright had spent two years watching men change under pressure. He’d watched farm boys become harder than steel. He’d watched confident men unravel after nights without sleep. He’d watched “quiet” soldiers turn out to be the ones who held the line when everything went wrong.

But these two moved with a kind of calm Cartwright didn’t recognize.

They didn’t walk like men scanning for threats.

They walked like men reading the air.

Captain Harrison introduced the taller one as Joseph Nicha—Apache.

At first, the name meant nothing to Cartwright. Later, he would hear fragments—stories about Joseph’s family, about older generations who survived because they learned to interpret land the way others interpreted written language. The second man was Thomas Big—Navajo—descended from people who endured forced removals and carried culture forward even when everything around them tried to erase it.

Harrison called them scouts. Cartwright, privately, called them an experiment.

The Germans were dug in five miles east. Well-positioned. Experienced. The kind of troops who’d already seen more than enough fighting. Mortars. Machine-gun positions. People who knew how to hold ground and punish anyone who moved carelessly.

And command had answered with two scouts who, to Cartwright’s eye, looked under-equipped.

He lit a cigarette and stared into the trees. This forest was already chewing through units like it had teeth. Mud, cold, confusion, sudden bursts of danger that came from nowhere and vanished just as fast.

This—he thought—was going to be another bad day.

That afternoon, the radio crackled with intelligence: movement confirmed. A German patrol, twelve men, led by Lieutenant Marcus Hoffman.

Hoffman’s name traveled fast on both sides. Not because he made speeches or sought attention, but because he stayed alive when others didn’t. He was known as precise, disciplined, difficult to surprise. The kind of officer who treated every step like a calculation and every risk like a cost.

His patrol wasn’t strolling through the woods. They were probing American positions. Testing. Listening. Looking for signs of weakness before the larger push that would later shake the Ardennes.

Captain Harrison called Joseph and Thomas into the tent. Cartwright followed, curiosity pushing through his skepticism.

A map lay open on the table. Harrison pointed to a section marked as Sector 7—dense woodland with limited lines of sight, minimal paths, and terrain that punished mistakes.

“Can you follow them?” Harrison asked.

Joseph didn’t lean over the map. He didn’t trace routes with his finger. He looked past the canvas wall, as if the map was only a simplified shadow of something real.

“We don’t need to follow them,” he said. “We need them to follow us.”

Cartwright gave a short, sharp laugh—more reflex than insult. “So the plan is to get them to chase you?”

Thomas spoke for the first time, quiet but steady. “They won’t think they’re chasing. They’ll believe they’re leading. They’ll believe their skill found the trail. That belief will carry them where we want.”

Cartwright’s jaw tightened. He’d heard plenty of confident plans. He’d watched too many of them fail.

Harrison, however, nodded slowly. “Do it,” he said. Then he looked directly at Cartwright. “You’re going with them.”

Cartwright’s cigarette hung between his fingers. “Sir?”

“You’ll observe,” Harrison said. “You’ll learn. And you’ll report exactly what happens. That’s an order.”

They stepped off at dusk: Joseph, Thomas, Cartwright, and Private Roscoe Whitmore—a kid from Tennessee with restless energy and a mouth that couldn’t stop filling silence.

As they checked gear, Roscoe kept asking questions.

How do you navigate without a map? How do you move in darkness? Why no boots?

Joseph didn’t answer. He inspected his gear with careful focus, as if every strap and pocket had a reason.

Thomas glanced at Roscoe once and said, almost gently, “You don’t defeat darkness by fighting it. You learn to move inside it.”

That was enough to shut Roscoe up.

The forest swallowed them quickly. No lights. No chatter. No wasted motion. Cartwright had done night patrols before—had learned the basics, thought he knew how to move quietly.

Then he watched Joseph and Thomas and understood how loud a “quiet soldier” could be.

They stepped where branches didn’t snap. They avoided leaf piles that would betray a footfall. They moved as if the ground was giving instructions under their soles. Their pace wasn’t fast, but it was certain. It wasn’t forced. It was practiced.

After roughly an hour, Joseph stopped.

He lowered himself into a crouch and touched the ground with fingertips—lightly, like someone checking the surface of water.

Cartwright saw nothing but dirt and damp leaves.

Joseph stood. “They passed here about three hours ago. Twelve. One is favoring his left leg.”

Cartwright stared at him. “From what?”

Joseph pointed out details Cartwright would never have noticed: a slight depth difference in impressions, the angle of a disturbed patch of soil, a faint smear on a stone that looked like nothing until Joseph framed it.

“Weight shift,” Joseph said. “And here—trace sign of irritation. Not a lot. But enough.”

Thomas examined a trunk and nearby brush. “They’re confident,” he said. “Moving in straight intention. Minimal attention to their sides.”

Joseph’s eyes remained fixed forward. “Then they’re going to learn.”

Several miles east, Hoffman’s patrol rested in disciplined formation. Hoffman cleaned his rifle, methodical. His men watched the treeline. Even their pauses looked planned.

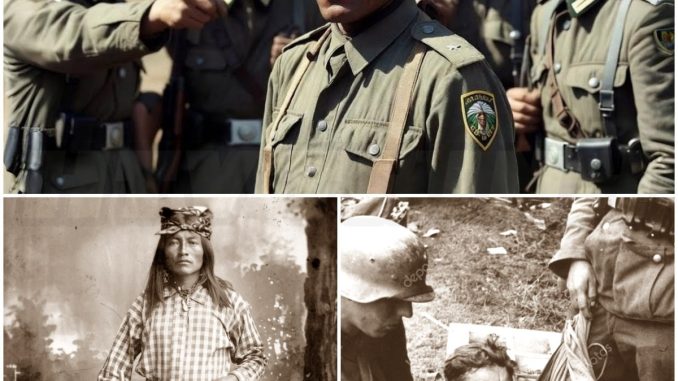

Corporal Heinrich Müller, however, couldn’t keep his voice down. He’d heard the talk about American Native scouts and treated it like a joke.

“They send trackers,” he said, exhaling smoke. “They think we’ll be afraid of old methods.”

The men laughed. Even young Wendelin Gottschalk—barely nineteen, newly assigned—let himself smile, relieved at the loosened tension.

Hoffman didn’t join the laughter. He’d fought in places where the enemy didn’t behave like textbook soldiers. He’d learned that confidence could be useful, but dismissal could be fatal.

Still, he let Müller talk, because morale had its own logic.

But the forest had begun to feel too quiet.

Joseph and Thomas moved ahead of the German patrol, leaving Cartwright and Roscoe tucked into dense cover. Through binoculars, Cartwright watched Joseph do something that looked almost foolish at first.

Joseph broke a branch at eye level—deliberate, obvious. Then he disturbed soil in a clean line. Then he left small items—things a trained soldier would interpret as careless loss.

And then Joseph did the one thing Cartwright hadn’t expected.

He vanished.

Not “melted back” the way a cautious soldier retreats. Not “hid behind a tree.” He was visible in a faint wash of moonlight… and then he simply wasn’t.

Cartwright blinked, tightened his focus, scanned. Nothing.

Roscoe whispered, barely able to control his voice. “Where did he go? I was staring straight at him.”

Cartwright didn’t have an answer.

Thomas repeated the same work—another obvious sign, another clear invitation—and he too disappeared into the landscape.

Cartwright felt a slow chill crawl up his spine. If he hadn’t watched them create that trail, he would have believed no one had been there at all.

At dawn, Hoffman’s patrol found the signs exactly as intended. Müller was energized, almost pleased.

“There,” he said. “Careless. We’ll catch them.”

Hoffman studied the trail carefully. It was too clean. Too readable. Too perfectly placed.

He raised his hand. The patrol stopped. Weapons lifted slightly. Eyes swept the trees.

“This is meant to be found,” Hoffman said. “A trail this obvious is an invitation.”

Müller scoffed. “An invitation from scouts like that? Sir, they’re probably running and dropping things without thinking. We can use it.”

Hoffman wanted to turn back. His instincts pressed hard against the order to continue. But he also had a mission: probe forward positions, gather intelligence, report.

So he moved them forward—but slower. More cautious. Flanks watched. Formation tighter.

They followed the trail for hours. The deeper they went, the more the woods seemed to swallow sound. No birds calling. No small movements in brush. Only boots, breath, and the feeling of being watched.

Then the trail split.

North into a narrow ravine. West toward higher ground.

Hoffman stopped at the decision point, reading it as a test.

Müller knelt by the northern line. “This looks fresher,” he said. “Deeper prints. They went this way.”

Hoffman made a choice that felt correct in theory. “We split. Six and six. We cover both. Regroup at the ridge in four hours. If contact—signal.”

Müller took the northern route. Hoffman took the west.

Cartwright watched from concealment as the Germans separated, each group swallowed by trees. Joseph appeared beside him so suddenly Cartwright almost flinched.

“Müller’s group first,” Joseph said quietly.

Cartwright swallowed. “What do you need from us?”

“Stay hidden,” Joseph replied. “Watch. Learn. If something fails, you return and report. But it won’t fail.”

Müller’s men moved into the ravine in disciplined spacing. The walls rose close, vegetation thick, visibility poor.

It was the kind of place that looked safe until you realized there was no easy escape.

The tracks continued down the center—until they didn’t.

They ended as if the person who made them had stepped into the air and disappeared.

Müller stared. “That makes no sense.”

One of his veterans checked the ground, frowning. “No turn. No climb. No reversal.”

The ravine seemed narrower now. Darker. Sound felt dampened, as if the air itself was absorbing it.

Müller opened his mouth to order a retreat—

And one man was simply gone.

No clear struggle. No obvious noise. One moment a soldier stood there; the next, space.

Müller’s voice cracked. “Contact! Rear—”

But there was nothing to aim at. No visible enemy. No target.

Another man vanished.

This time Müller saw only a flicker of movement—too fast to name—then nothing. Panic spread, and rifles fired into branches and shadows, rounds ripping leaves and bark without finding anyone.

And then the forest returned to silence.

Terrible silence.

Now only three remained: Müller, Wendelin, and Kohl.

Wendelin’s hands shook around his rifle. “Where did they go?”

Müller backed toward the entrance. “Move. Now.”

They ran—no longer soldiers in formation, just people trying to escape a place that didn’t behave like a normal place. But the path looked wrong. The ravine seemed rearranged. Brush blocked routes they’d used minutes earlier.

Wendelin whispered, stunned. “This can’t be real.”

Müller had no answer. He had fought for years and seen countless strange moments in war. But this felt like something beyond ordinary tactics—like fighting the environment itself.

Joseph moved with quiet inevitability, using restraint and control rather than noise. Thomas worked from angles no one expected, shaping attention and direction like a craftsman. Men were separated, disoriented, subdued, concealed.

Now Müller’s group was exhausted—burning energy, making choices with fear instead of discipline.

Kohl tripped hard and went down. A sharp sound, then a cry. His ankle twisted badly.

Müller turned back, torn between training and survival. He grabbed Kohl’s arm. “Up. We don’t leave you.”

Kohl’s face was pale. “I can’t.”

Then Müller heard it—movement in brush that wasn’t wind. Not loud. Not obvious. Just… close.

He let go.

Kohl’s eyes widened in disbelief. “No—please.”

Müller backed away. “I’m sorry.”

He ran. Wendelin followed.

Behind them, Kohl called out again—and then the sound stopped abruptly.

By midday, Hoffman returned to the rendezvous point. Müller was not there. The radios hissed with static. Hoffman waited. One hour. Two.

He sent two men to trace Müller’s route.

They came back pale and shaken. One veteran couldn’t keep his hands steady while trying to light a cigarette.

“They’re gone,” he said.

Hoffman grabbed him by the collar. “Explain.”

The man swallowed hard. “We found the ravine. Signs of confusion. Equipment left behind. Helmets, packs… But no clear trail out. No obvious direction. It’s like they walked into the trees and didn’t come back.”

Hoffman released him, mind racing. Six men didn’t vanish without reason. But nothing in the scene offered a clean answer.

He looked at the five remaining men and made the decision he wished he’d made earlier.

“We’re pulling back. Mission is over. We leave now.”

They moved quickly, tight formation. No stragglers. No gaps. Hoffman was determined to make any ambush costly.

But the forest stretched in ways that felt impossible. Landmarks repeated. A split-trunk tree appeared again as if it had followed them.

One soldier whispered, voice thin. “Sir… we’ve been here before.”

Hoffman checked his compass. The needle drifted, refused to settle.

He forced calm. “We find water. Streams lead to valleys. Valleys lead to roads.”

They searched.

No stream.

No water.

Only trees and quiet.

Night fell suddenly, heavy and absolute. Hoffman ordered a defensive position—no fire, no light. Just men in a rough circle, rifles outward, waiting.

Hoffman stayed awake.

And still, by dawn, two men were gone.

Their weapons remained. Their gear remained. The men did not.

Wendelin stared at the empty spaces, face blank with shock. “How?”

Hoffman had no tactical explanation that fit. He was no longer thinking like an officer managing a patrol. He was thinking like someone trapped inside a problem that refused to obey rules.

Three left: Hoffman, Wendelin, Keller.

Hoffman made a choice he never expected to make in this forest.

“We surrender.”

Wendelin blinked. “Sir?”

“We can’t fight what we can’t locate,” Hoffman said. “We can’t escape what we can’t navigate. Surrender is the only chance.”

He raised his hands and called out in English. “We surrender. We will not resist.”

Silence.

Then, close enough that Hoffman felt the presence before he understood it, a voice spoke calmly.

“Lower your weapons. Place them down. Step back ten paces.”

Hoffman obeyed. Wendelin and Keller followed.

Joseph emerged from the trees. Thomas from another angle. Cartwright and Roscoe appeared behind them.

Four men.

Hoffman stared, drained. Twelve men reduced without a traditional firefight.

Joseph spoke evenly. “Your men are alive. Secured. Hidden. They will be transferred as prisoners.”

Hoffman didn’t speak. He simply watched Joseph as if he were trying to understand a language he’d never learned.

Joseph continued, not boastful, just certain. “You came here believing training and equipment were enough. This place rewards understanding. It punishes arrogance.”

Cartwright stepped in to secure the prisoners. Roscoe worked quickly, quieter than Cartwright had ever seen him.

As they moved out, Wendelin looked back at Joseph, exhausted and shaken. “How did you do it?”

Joseph met his eyes. Something passed there—recognition, perhaps, that both were soldiers caught in a war larger than themselves.

“You were taught to push against land,” Joseph said. “We were taught to move with it.”

Back at the American camp, Captain Harrison listened as Cartwright reported: twelve Germans accounted for, most captured, minimal risk to American troops, no confirmed exchange of fire.

Harrison’s expression tightened with the weight of it. “The Army will want a full debrief,” he said. “This changes how we operate here.”

Cartwright, hands steadier now, looked at Joseph. “I misjudged you.”

Joseph shook his head. “You believed what your training taught. Now you’ve seen another way.”

Word traveled quickly. Units requested Native scouts. Officers who had doubted suddenly asked questions. Methods once dismissed became valuable. Over the months that followed, Joseph and Thomas taught others how to read terrain, how to move without announcing themselves, how to treat the forest as information rather than an obstacle.

German reports noticed the shift too—warnings about scouts who seemed to appear and vanish, who found patrols in terrain that should have protected them. But warnings were not the same as solutions.

You can’t out-muscle what you can’t locate.

You can’t outpace what keeps you disoriented.

And you can’t quickly replace knowledge refined over generations.

Joseph and Thomas served through the end of the war. They returned home in 1945 without public attention—no grand parades, no loud headlines. Their work lived mostly in unit reports and the quiet memory of those who had seen it.

Cartwright stayed in touch with Joseph. Letters went back and forth for years. In 1952, Cartwright finally asked the question that never left him: How did you make an entire patrol seem to vanish?

Joseph’s reply arrived weeks later, handwriting careful.

We didn’t make them vanish. We didn’t turn the forest into a weapon. We let it be what it already was. The land confuses those who don’t understand it. It exhausts those who fight it. It helps those who listen. People think terrain is neutral. It isn’t. It remembers. If you learn how to move as part of it, it will hide you and reveal others. That’s not mysticism. That’s practice.

Decades later, historians gave recognition to code talkers after years of silence. Scouts received less public credit—often small mentions, brief notes. But veterans remembered. Roscoe told the story every holiday, gesturing wildly, describing men who could disappear into trees. His grandchildren thought he exaggerated. They didn’t realize he was holding back, trying to make it sound believable.

Cartwright wrote about it in a memoir published in 1967. Readers assumed the language was metaphor—a poetic way to describe forest warfare. Only those who had been there understood he meant it plainly: a patrol had been neutralized by methods that looked impossible from the outside.

Even Wendelin—who survived—spoke about it years later. He talked about the helplessness of being watched without seeing who watched. About the way fear grows when the environment itself feels against you. About the moment he realized the jokes had been foolish.

Over time, pieces of Joseph and Thomas’s approach filtered into training—specialized units, survival schools, fieldcraft programs. Some techniques can be taught. But the deeper lesson—the relationship to land, the patient attention, the sense of moving with an environment rather than against it—was harder to pass on through manuals.

In one last letter before Joseph’s death in 1978, he wrote about the future. He wrote that the world moved faster and forgot easily. He wrote that technology is useful, but it doesn’t replace judgment. He wrote that sometimes the quickest step forward begins by respecting older truths.

He did not claim to be extraordinary.

He simply claimed to have listened.

And in the Hürtgen Forest, in the cold fog of October 1944, that was enough to change the outcome—before the other side even understood what was happening.

If you want more stories like this—moments where the overlooked details decide everything—subscribe, like, and comment with the next historical event you want explored.

History isn’t only the famous generals and the big maps.

Sometimes it’s four men in a silent forest, proving that the oldest skills still matter.