In many pre-modern societies, punishment was not always designed to end a life or even to cause immediate physical injury. Instead, justice often relied on exposure, endurance, and the moral judgment of the surrounding community. One of the most revealing examples of this approach was the cangue, a wooden restraint once used widely across East Asia as a form of public punishment.

The cangue, known in Chinese as jia and appearing in related forms in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan, functioned as a legal instrument that blended law, shame, and social pressure. It was not officially intended to kill. Yet in countless cases, it placed the wearer in conditions where survival depended entirely on others. In this way, the cangue reveals how punishment could become lethal without ever being labeled as execution.

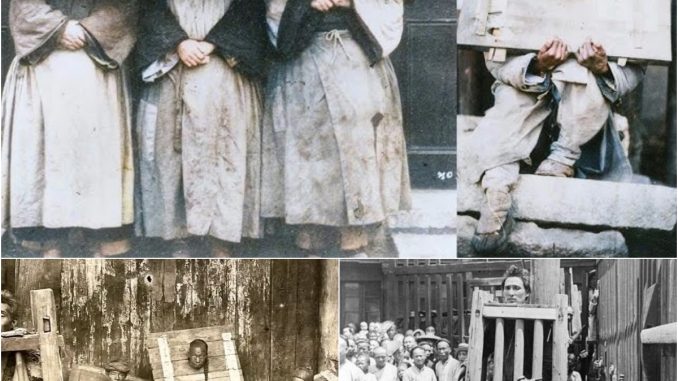

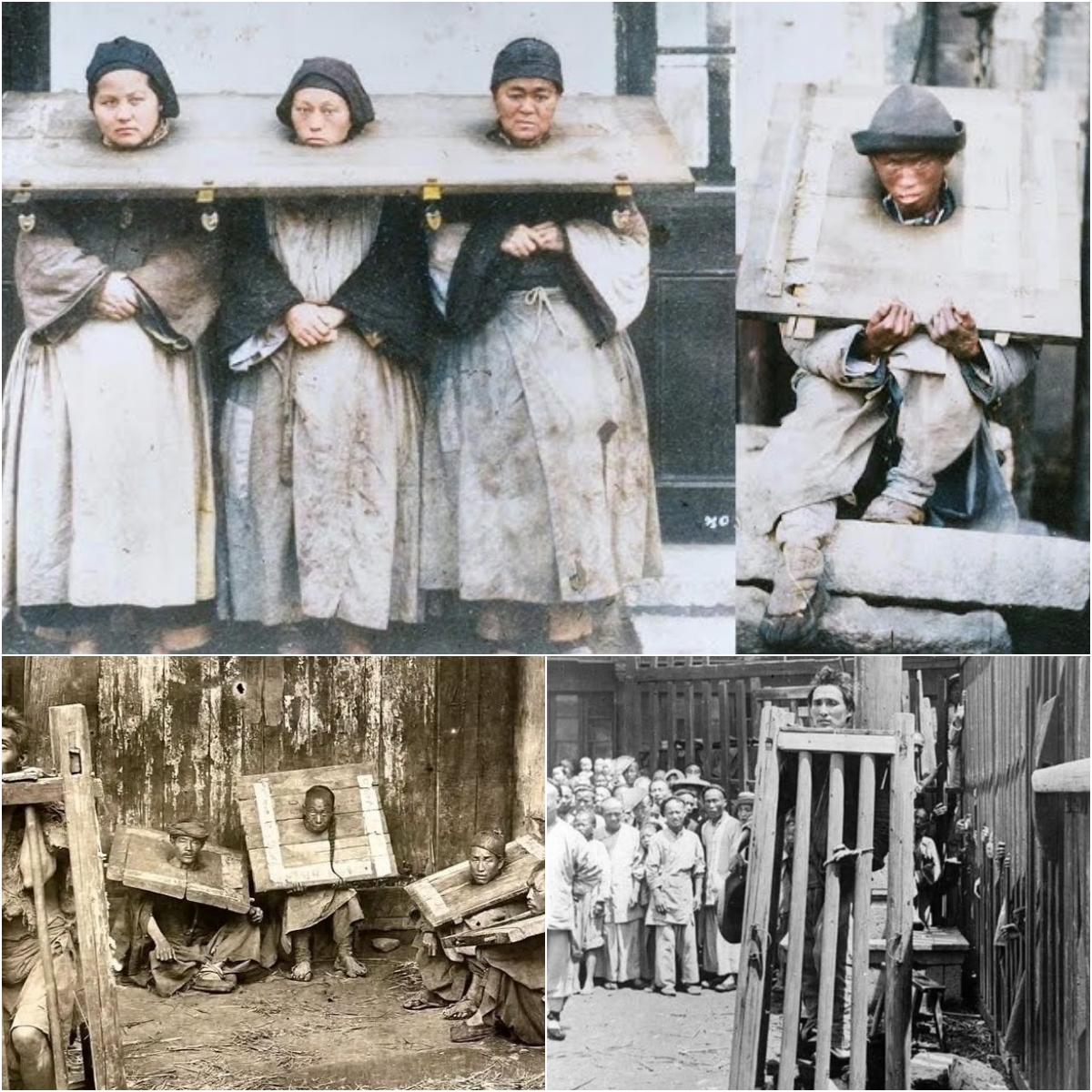

At its core, the cangue was a large wooden board fitted around the neck. Typically made from thick planks, it consisted of two halves locked together, with a circular opening that held the neck firmly in place. The board extended outward over the shoulders, sometimes reaching nearly a meter in width. Heavier versions could weigh dozens of kilograms, making prolonged standing or walking extremely difficult. Some designs also included holes for the wrists, restricting the arms and preventing the wearer from performing basic tasks.

The physical function of the device was simple: it limited movement. But the deeper purpose was symbolic. The cangue transformed the human body into a public display. Unlike imprisonment, which removed individuals from view, this punishment placed them directly in the center of daily life. Markets, crossroads, temple entrances, and government buildings became stages where justice was performed before the eyes of the community.

Sentencing typically followed a formal legal process. Once judgment was delivered, officials escorted the condemned person to a public location and locked the cangue in place. Often, the offense and duration of punishment were written directly onto the wood in large characters. This ensured that every passerby knew why the individual stood there and what behavior had been condemned.

The crimes that led to this punishment varied widely. Theft, fraud, violations of moral codes, disobedience, and minor administrative offenses could all result in a cangue sentence. The punishment was meant to be corrective rather than terminal. The idea was that public exposure would restore social order by deterring others and compelling the offender to reflect on their actions.

However, the reality of life inside the cangue was far more complex.

Once restrained, the wearer faced immediate challenges. Eating required assistance, as the board prevented lifting food to the mouth. Resting was difficult, since lying down flat was nearly impossible. Exposure to sun, rain, wind, or cold became constant. Over time, physical strain accumulated. Neck pain, exhaustion, dehydration, and weakness were common consequences.

What truly determined the outcome, however, was the response of the surrounding community.

In societies influenced by Confucian values, law did not operate in isolation. Morality and social relationships played a central role. The cangue deliberately placed responsibility beyond the court. Neighbors, strangers, family members, and passersby all became participants. They could offer water, food, or shelter from the elements. Or they could withhold assistance entirely.

If the offense was considered forgivable or minor, the wearer might receive help and survive the sentence. If the crime carried strong stigma, assistance might disappear. In those cases, prolonged neglect could lead to severe physical decline. Death, when it occurred, was not declared by law but emerged as a consequence of social rejection.

This structure allowed punishment to operate without direct state responsibility for fatal outcomes. The law restrained the body, but society decided mercy.

The psychological dimension of the cangue was as powerful as its physical effects. The wearer endured constant observation. Every glance reinforced their status as an offender. Every whisper or act of avoidance confirmed exclusion. Over days or weeks, this experience could erode identity and dignity, even in cases where physical survival was possible.

Public humiliation was not an accidental side effect. It was the core mechanism.

Historical records suggest that this method was particularly effective in tightly knit communities where reputation mattered deeply. Shame was understood as a force capable of shaping behavior more efficiently than violence. By exposing wrongdoing rather than hiding it, authorities reinforced shared moral norms.

Variations of the cangue appeared across East Asia, reflecting local adaptations of a shared legal philosophy. In Vietnam, similar wooden restraints emphasized public visibility but were often lighter. In Korea, related devices served primarily as symbolic punishment rather than prolonged immobilization. In Japan, visual records from the early modern period show comparable instruments used to reinforce social order, though legal practice differed.

Despite regional differences, the underlying logic remained consistent. Punishment did not isolate the offender from society; it bound them to it in the most uncomfortable way possible.

By the nineteenth century, this system began to face criticism. As Asian states encountered new legal ideas through reform movements and foreign influence, public humiliation increasingly came to be seen as incompatible with emerging notions of human dignity. The emphasis shifted toward codified punishment, incarceration, and standardized legal rights.

In China, the cangue was formally abolished in the early twentieth century during a period of sweeping legal reform. Similar practices faded elsewhere as modern legal systems replaced community-based enforcement with centralized authority.

Today, the cangue survives only in museums, historical illustrations, and archival texts. Yet its legacy remains important. It demonstrates how punishment can operate without overt violence, relying instead on social pressure and dependence. It also shows how easily justice can slide into dehumanization when survival is placed in the hands of public judgment.

Studying the cangue is not about sensationalizing suffering. It is about understanding how earlier societies balanced law, morality, and power. It forces modern readers to confront uncomfortable questions: when punishment depends on shame, who decides when enough is enough? When survival relies on mercy, what happens to those deemed unworthy of compassion?

The disappearance of the cangue reflects a broader transformation in legal thinking. Modern justice systems increasingly reject humiliation as a tool, favoring proportionality, accountability, and rehabilitation. These principles did not emerge automatically. They developed in response to centuries of practices that blurred the line between correction and cruelty.

Remembering the cangue helps ensure that justice does not return to forms that erase dignity in the name of order. History offers no comfort, but it offers clarity. By examining how punishment once worked, societies can better understand why humane legal reform matters—and why the quiet tools of humiliation can be just as destructive as overt force.