What Rome Did to Captured Queens Was a Different Kind of War

You can hear it before you see it.

A deep, metallic rhythm—chains shifting, ornaments clinking, the steady drumbeat of a city turning victory into theater. Rome doesn’t just defeat an enemy on the battlefield. Rome defeats them again in the streets, in front of an audience large enough to turn humiliation into legend.

It’s the third century CE, and the capital is packed so tightly that you can’t step away even if you want to. People press against stone walls and columns, craning their necks for a glimpse of the procession. Vendors shout. Children sit on shoulders. The city has paused its ordinary life for a single purpose: to watch Rome prove, publicly, that no ruler on earth is beyond its reach.

And then she appears.

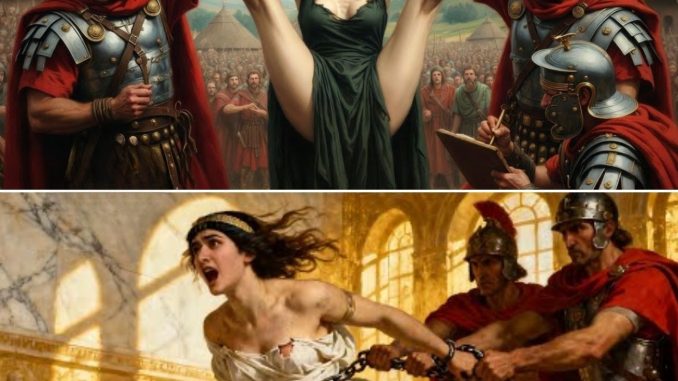

Zenobia of Palmyra—once called the “Queen of the East”—moves forward under the weight of display. Roman writers describe her as richly adorned in the parade, burdened with jewelry and chains meant to be seen. The point isn’t practicality. The point is symbolism: Rome is showing the crowd that even a queen who once commanded armies can be turned into a moving trophy.

The crowd roars—not because they know her personally, but because Rome has taught them what she represents: defiance crushed.

Zenobia’s face, in the accounts that survive, is not the face of someone pleading. It is the face of someone calculating. Because she understands the most frightening part of a Roman triumph:

Not the parade itself.

The uncertainty at the end.

The Roman Triumph Was Not a Celebration. It Was a Message.

Movies often portray a triumph like a grand festival: music, banners, smiles. But the triumph was also psychological warfare, staged with the precision of a ritual.

It began outside the city and wound through Rome’s heart, ending at the Capitoline Hill. Along the route, the victor displayed captured wealth—art, coins, sacred objects, and treasures meant to announce, “Everything that belonged to you now belongs to us.”

After the spoils came images and symbols of conquest: painted scenes of fallen cities, defeated armies, surrendered strongholds. Then came exotic animals from faraway lands, proof that Rome’s reach extended beyond the familiar world.

And finally came the prisoners.

Not all prisoners were equal in the eyes of a Roman crowd. Common soldiers might be marched together, heads down, moving toward slavery or forced labor. But the real silence—the heavy pause—arrived with the rulers.

A defeated king. A captured prince. Or, most unforgettable of all, a queen.

Rome understood something cruelly practical: a ruler brought low is more powerful as propaganda than as a corpse.

But keeping a captured queen alive created a different problem. A living queen might become a symbol. A rallying point. A story that outlived Rome’s victory.

So the ending of a triumph mattered more than the beginning. And the person walking in chains didn’t know which ending they would receive until the last steps were taken.

Two Doors at the End of the Road

For some captives, Rome chose exile or controlled living—comfortable enough to look like mercy, restrictive enough to prevent influence. For others, Rome chose disappearance: execution, imprisonment, or a fate that ended their public story immediately.

This decision was political. It depended on the emperor, the mood of the city, and the danger Rome believed the captive still posed.

Zenobia knew this. As she walked, she wasn’t simply enduring shame. She was reading faces. Measuring reactions. Trying to guess which version of Rome she would meet at the end.

Because Zenobia was famous.

And famous captives forced Rome into a difficult calculation: kill them and risk creating a martyr, or keep them alive and prove that even greatness can be domesticated.

Roman accounts suggest Zenobia survived and lived in guarded comfort outside Rome, becoming part of the imperial story rather than a spark for future rebellions. If that is true—and many historians consider it plausible—then Zenobia’s “mercy” came with a hidden price: she would never again live as a sovereign.

A gilded cage is still a cage.

Before Zenobia, Another Queen Learned Rome’s Method

Two centuries earlier, far from the marble streets of Rome, another queen discovered that Rome’s cruelty did not always arrive with ceremony.

Her name was Boudica, queen of the Iceni in Britain.

Her husband had tried to navigate Roman rule through compromise. He sought stability—an arrangement that might allow his family and people to survive alongside empire. When he died, the agreement did not protect them. Roman officials moved quickly, asserting control and punishing resistance.

The ancient historian Tacitus describes how Boudica and her family were publicly humiliated as a warning to the wider region. The details, even in careful retellings, make one thing painfully clear: Rome wanted to demonstrate that local royalty meant nothing once Rome decided to take everything.

But the story did not end in submission.

What Rome underestimated—again and again—was how humiliation could become fuel.

Boudica became a rallying force for tribes who had been enduring Roman demands, Roman taxation, and Roman arrogance. Her uprising was one of the most serious threats Rome faced in early Britain. Cities were attacked and burned, Roman authority shook, and panic spread through the province.

In the end, Rome’s discipline and organization overcame a coalition driven by fury and grief. Ancient sources describe Boudica choosing death rather than capture—an act that reads, in context, like a refusal to be paraded, displayed, or turned into Rome’s lesson.

Whether one sees her as a tragic figure, a political leader, or a symbol of resistance, her story reveals Rome’s constant pattern: punishment was never just about the target. It was aimed at everyone watching.

Another Queen Survived—And That Was the Cruelty

Even more unsettling than execution is a different Roman strategy: keeping a captured queen alive long enough to erase her meaning.

That is where the story of Thusnelda enters.

Thusnelda was connected to Arminius, the Germanic leader associated with Rome’s devastating defeat in the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE, when three Roman legions were destroyed. Roman writers describe the shock that rippled through the empire; later traditions even claim the emperor was haunted by the loss.

Rome could not easily undo that humiliation. So when Rome could not seize the rebel leader, it targeted what it could seize: family, lineage, symbols.

Thusnelda was captured and later displayed in a Roman triumph led by Germanicus. Ancient sources describe her presence as part of Rome’s effort to reclaim pride: “Look,” the procession implied, “we can still take something from the man who embarrassed us.”

And she had a child—an heir—whose fate is one of the bleakest examples of Rome’s long memory.

Because the most effective revenge is not always immediate.

Sometimes it is generational.

Thusnelda’s story is often remembered not for a dramatic ending, but for a slow stripping away of identity. Once taken into Rome’s control, her public role ended. Her personal story became something Rome could manage: private, quiet, controlled. Her son, according to later accounts, did not grow into a leader of his people. He was absorbed into Rome’s system, turned into a tool of Roman spectacle.

Rome did not merely want to win a war. Rome wanted to prevent the next one.

Why Captured Queens Terrified Rome

A captured king could be replaced. A captured general could be forgotten. But a queen—especially one with a story larger than the battlefield—could become myth.

Queens carried symbolism that Rome struggled to control:

- They represented dynasties and bloodlines, not just armies

- They embodied legitimacy in the eyes of their people

- They could inspire loyalty even in defeat

- They could turn into martyrs if killed

- They could become living warnings if kept alive

So Rome experimented with outcomes.

Sometimes it executed. Sometimes it exiled. Sometimes it displayed a queen publicly and then quietly removed her from history.

And sometimes it did something more effective than killing: it absorbed the bloodline into Rome itself, so that within a few generations the identity of the conquered dissolved into the identity of the conqueror.

If Zenobia truly lived in a villa near Rome, married into Roman society, and watched her children grow up in Roman customs, then Rome achieved something deeper than victory. It achieved assimilation—turning a rival empire into a footnote inside Roman aristocracy.

That kind of ending is difficult to dramatize. It doesn’t look like punishment.

But it is.

The Empire’s Quiet Skill: Turning People Into Symbols

Rome was brilliant at staging power. But its greatest skill was not in the parade.

It was in the story afterward.

A triumph was the opening chapter of Rome’s narrative: “We are inevitable.” What came next was the closing chapter: “And we will decide what remains of you.”

If a queen died, Rome could claim finality.

If a queen lived under Roman control, Rome could claim superiority.

If her children grew up Roman, Rome could claim permanence.

That is why the phrase “worse than death” resonates in stories about captured queens. Not because every queen endured the same fate, and not because every ending was equally brutal—but because Rome’s goal was often the same:

To make sure the conquered could not return to themselves.

What This Story Is Really About

It’s tempting to read these accounts as ancient spectacle—distant, dramatic, unreal. But the logic behind them is painfully familiar. Powerful states have always understood that domination isn’t only military. It’s psychological. It’s cultural. It’s about controlling what people believe is possible.

Rome wanted the world to learn a lesson:

You can build an empire.

You can crown yourself.

You can resist.

But if Rome decides you are a threat, Rome will not only defeat you.

Rome will redefine you.

Zenobia walking through the streets, uncertain of her fate, becomes more than a historical image. She becomes the symbol of every ruler who discovers that power can be taken—and then repackaged by someone else.

And Boudica’s refusal to be captured becomes more than tragedy. It becomes a warning about what happens when humiliation is used as governance.

Thusnelda’s disappearance into Rome’s system becomes more than personal loss. It becomes a blueprint for how empires erase resistance without leaving obvious scars for history to photograph.

The Last Steps

Imagine Zenobia again, nearing the end of the route. The cheers are behind her now. The city’s noise turns into a dull roar. The guards’ faces are unreadable. She cannot see the emperor. She cannot see the decision.

She can only keep walking.

Because in Rome, the parade wasn’t the punishment.

The punishment was understanding—too late—that your fate had become Rome’s story to edit.

And Rome, more than almost any empire in history, knew exactly how to edit a life.