The “Last Enslaved Woman of Georgia” Claim, and What a Careful Telling Can Actually Prove

Savannah, Georgia, in the mid-1930s was a city carrying two timelines at once. On the surface, it was struggling through the Great Depression like much of the country, with families stretching paychecks and neighborhoods relying on mutual help to get by. Underneath, Savannah also carried an older history in its streets, its architecture, and its long memory of labor systems that had shaped the South for generations.

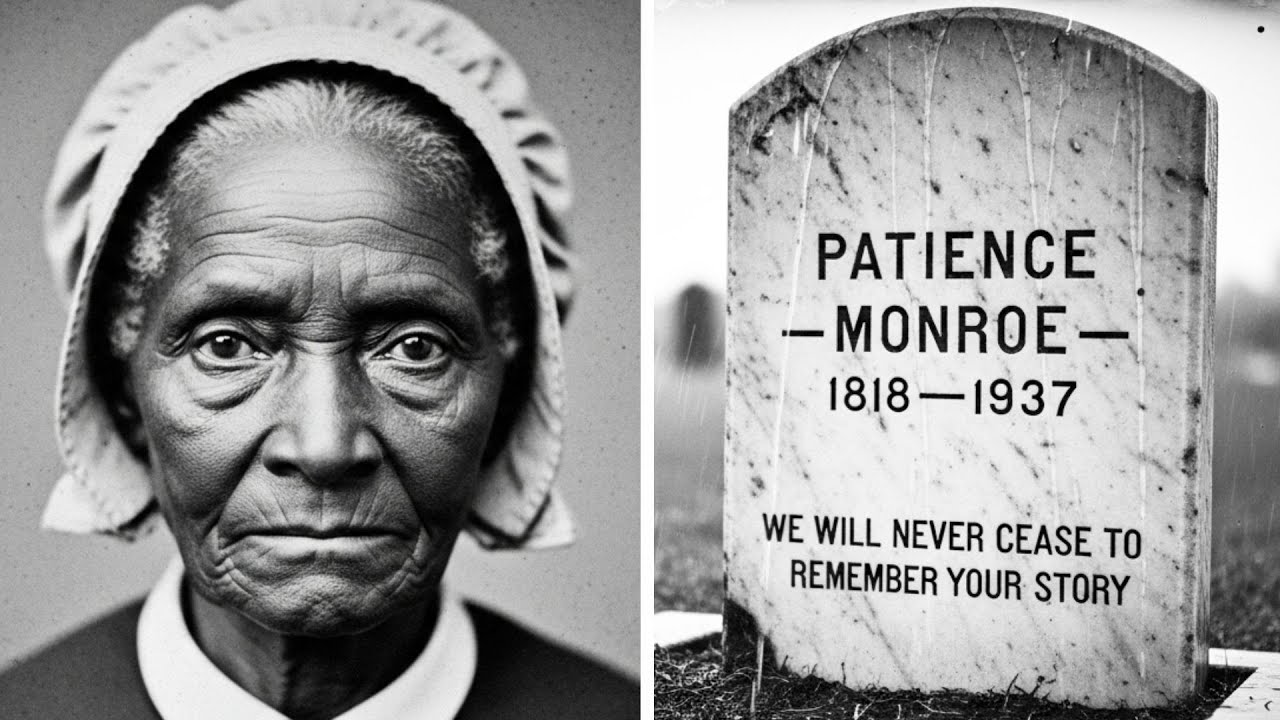

In that setting, a story began to circulate about an elderly woman living quietly on the edge of the city—someone neighbors simply called Miss Patience. People said she was older than anyone could reasonably be. They said she remembered a world that most Americans knew only through textbooks and family whispers. And they said that when she spoke, she sounded less like a single storyteller and more like a living archive.

As with many viral historical narratives, the most responsible approach isn’t to treat the account as a supernatural thriller. It’s to ask: what can be verified, what is likely, what is uncertain, and how do we talk about painful history without turning it into spectacle?

A woman known as “Miss Patience”

In the version that spread through local rumor, Miss Patience lived in a small cabin in a working-class neighborhood where people looked out for one another. Her home was modest, weathered, and practical—more shelter than statement. She was described as a quiet figure who kept to herself but remained recognizable to generations of residents who grew up seeing her in the same place year after year.

Neighbors claimed she spoke in an older cadence, with the influence of Sea Islands speech patterns, and that she rarely talked about the past unless she trusted the listener. That detail matters, because it fits the way many survivors and witnesses of historic trauma actually speak: cautiously, selectively, and often only after long periods of relationship and safety.

The extraordinary part of the story, of course, was her age. Accounts often claimed she had lived beyond 110, sometimes as high as 119, and that she had been born into slavery in Georgia. If true, that would place her among the last living Americans with direct memory of bondage in the United States.

The question of age, and why it’s hard to confirm

Extreme longevity claims are difficult to verify even today, and in the 19th century they were often impossible to document precisely for Black Americans, especially those born under slavery. Birth records could be missing, inconsistent, or recorded in ways that reduced a person to property rather than an individual with a legally recognized identity.

That doesn’t mean longevity claims are automatically false. It means the evidence tends to be fragmentary: census entries, church records, death certificates, family testimony, and newspaper mentions that may conflict with one another. A careful telling must acknowledge that uncertainty.

In the most grounded version of this story, a physician is called to see Miss Patience after a fall or illness. The doctor is surprised by how frail she appears and yet how alert she remains. The doctor notices signs of a life that has been physically demanding, and begins writing notes out of professional curiosity and concern.

This is where a responsible narrative shifts gears: not toward sensationalism, but toward documentation. What does the doctor observe? What can be explained by age, chronic hardship, or limited access to healthcare? What is outside normal expectation? And most importantly, what is interpretation and what is evidence?

Memory as testimony, not entertainment

The heart of the story is not a “mystery” designed for clicks. It is the idea that an elder, late in life, decided to speak—carefully—about what she had seen and lived through, and about what she feared would be erased if she died without leaving a record.

In many communities, older residents carried history through oral storytelling because formal archives excluded them. For enslaved people and their descendants, that exclusion was not an accident; it was part of a system that preserved transactions and erased inner lives.

So when Miss Patience describes the past, the point should not be to linger on cruelty. The point is to show what daily existence felt like under coercive systems, how families tried to protect one another, and how culture—songs, language, faith, and community—helped people remain human under conditions designed to deny their humanity.

A trauma-informed telling can acknowledge hardships without graphic detail. It can describe the constant exhaustion, the fear of separation from family, the uncertainty of tomorrow, and the way people learned to find dignity in small choices when bigger choices were denied.

And it should also emphasize resilience: the ways people taught children quietly, the ways communities cared for one another, the ways spirituals and stories carried identity forward when written records did not.

“I remember more than my own life”

Viral versions of this narrative often introduce a supernatural element: that Miss Patience didn’t just remember her own experiences, but seemed to carry memories that belonged to others, sometimes speaking in shifting voices or dialects.

Handled poorly, this becomes exploitative—turning collective trauma into a horror device. Handled responsibly, it can be framed as something far more human: the way elders can embody a community’s memory. People who live long lives in tight-knit neighborhoods often become keepers of stories—not because they possess other people, but because they’ve listened, remembered, and carried those accounts with care.

There’s also a psychological truth here that doesn’t require supernatural claims: trauma can be intergenerational. Families pass down stories, silences, fears, and protective instincts. Communities pass down warnings and wisdom. Over time, those inheritances can feel like memories, because they shape identity so deeply.

If Miss Patience spoke as if she had “absorbed” other stories, the simplest explanation may be the most plausible: she spent decades hearing people confide what they couldn’t safely say elsewhere. She remembered details others forgot. She became, in effect, a living repository.

That is extraordinary on its own.

What historians and journalists would try to verify

If a historian were presented with a claim like “the last enslaved woman of Georgia,” they would not begin with the most dramatic scenes. They would begin with records and cross-checking.

They would look for:

-

Census references that align across decades

-

Church membership rolls or baptisms

-

Any consistent mention of birthplace and approximate year

-

Death certificate details and who reported them

-

Local newspaper items, even brief ones

-

Oral history that can be compared across unrelated sources

A journalist, similarly, would focus on careful language: “she was believed to be,” “records suggest,” “neighbors recalled,” “documentation is limited,” and “some details remain unconfirmed.”

That approach protects the subject’s dignity and protects the reader from being misled.

Why these stories matter even when details are uncertain

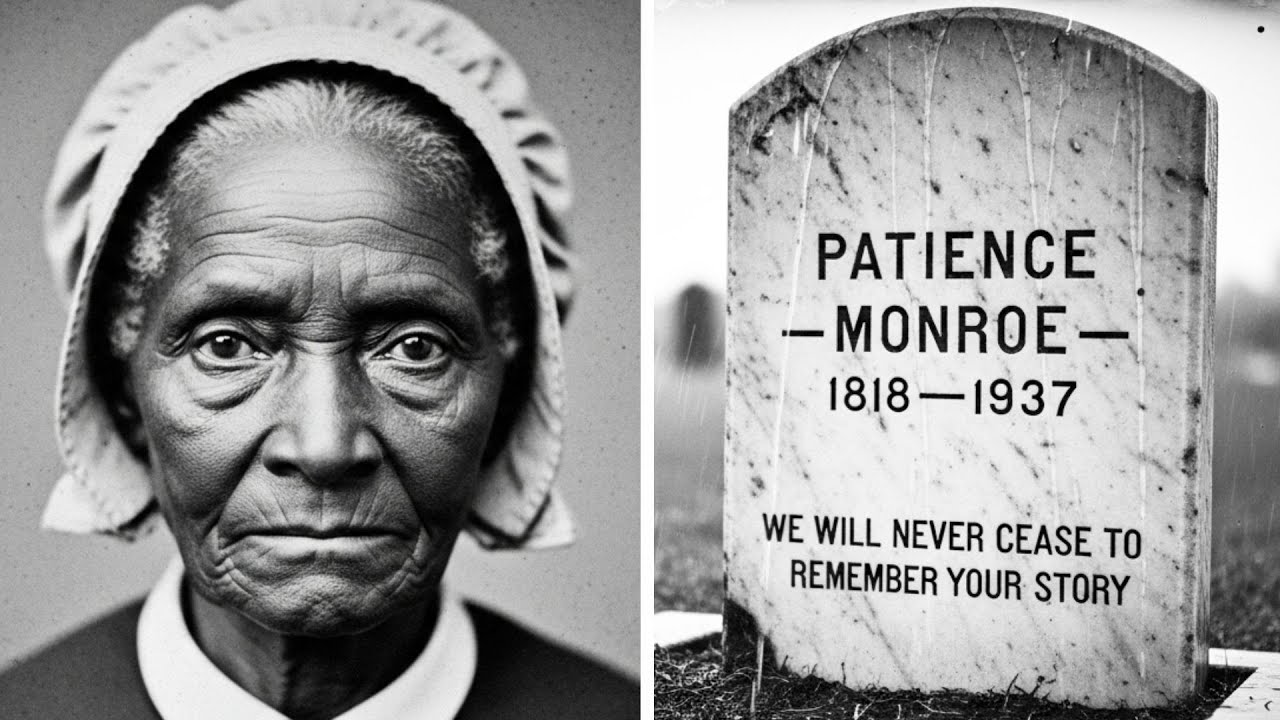

Whether Miss Patience was 109, 115, or 119, the deeper significance is what her life represents: a bridge between eras that many would prefer to keep separated. Her presence forces a truth that is easy to avoid when history is reduced to dates and abstractions: real people lived it, carried it, and tried to survive it.

And her desire to be heard—if that desire is the heart of the story—speaks to another reality. When history is sanitized, it becomes easier to deny. When it is told with care and accuracy, it becomes harder to ignore.

The value of testimony is not in creating shock. It is in creating understanding.

A dignified, AdSense-safe rewrite can highlight:

-

How aging witnesses are treated by communities

-

How memory becomes historical evidence when archives are incomplete

-

Why the lack of records for enslaved people is itself a historical fact

-

What “bearing witness” means, ethically, in journalism and research

-

How communities preserve truth when institutions do not

A closing scene rooted in respect

The most responsible ending is not a supernatural crescendo. It is a quiet recognition: an elder’s voice fades, and with it a kind of living connection to the past becomes rarer.

If Miss Patience asked someone to promise her story would not be forgotten, that request should be treated as the point of the narrative. Not her “curse.” Not her “gift.” Her insistence that people tell the truth, with care, when she could no longer speak for herself.

That promise—if honored through writing, teaching, archiving, and public memory—becomes a form of justice that does not require dramatization. It requires accuracy, humility, and refusal to turn pain into entertainment.

In the end, the most stunning part of a story like this isn’t that one person lived an unusually long time. It’s that an entire era can vanish if no one chooses to remember it honestly.