The Last Bid on Broughton Street

The auction house on Broughton Street was rarely quiet. Even when voices lowered and boots stopped scraping, the room still carried a restless energy—like it remembered every transaction that had happened there and refused to forget. Men treated the place like a marketplace and a theater at the same time. They came with practiced faces, coins tucked away, and a casual confidence that said the outcome would always bend to their will.

But on an August afternoon in 1859, something shifted.

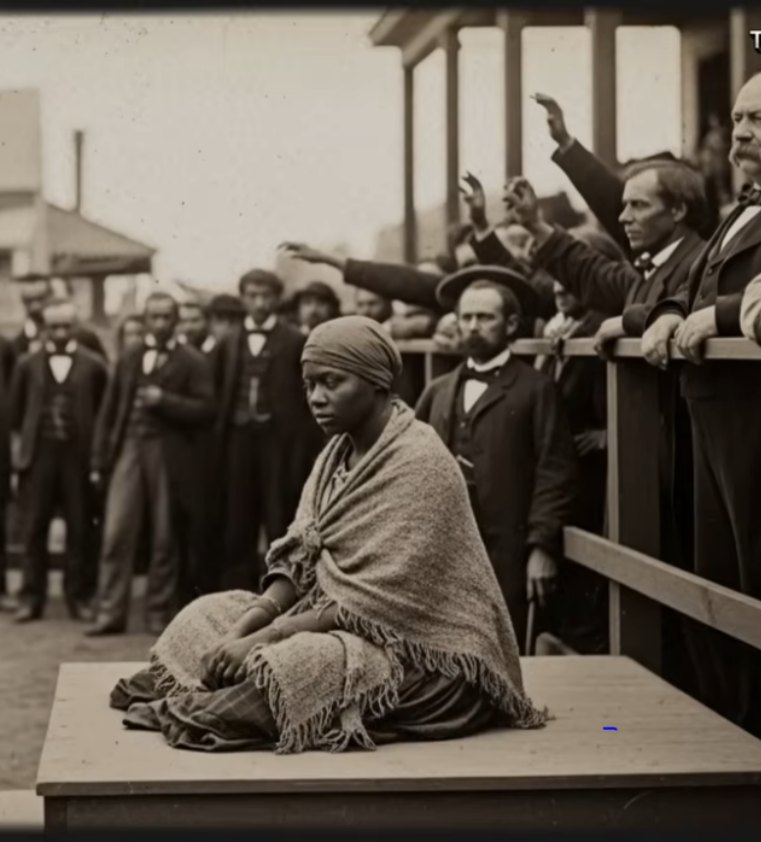

Not because a fight broke out, or because a famous buyer arrived. The change came when Lot Forty-Three was brought to the platform, and for a brief moment, even the most hardened men seemed to lose their appetite for noise.

The woman was introduced with a name the auctioneer spoke too quickly, as if saying it clearly would make it heavier. “Celia,” he muttered, then added a list of skills in the same tone a man might use for tools: cook, helper, knowledgeable with herbs. A few heads lifted at the last part. A few eyes dropped.

In that room, people understood certain things without having to say them.

Celia’s posture was steady. Her face held no performance—no begging, no pleading, no anger that could be used against her. It was a kind of calm that unsettled men who believed fear was the only language power could produce.

The bidding was thin and reluctant. Hands hovered, then fell. One by one, men looked away as if the air had turned sharp.

Only one buyer leaned in.

Thomas Cornelius Pewitt had recently risen in wealth and wanted the world to notice. He came with the swagger of someone who believed money could purchase not just labor but control, not just property but peace of mind. When the auctioneer called for an opening, Thomas raised his hand without hesitation.

The hammer fell quickly.

Twelve dollars, people later whispered—an amount so small it sounded like a joke told by the devil. Thomas took it as proof of his cleverness. A bargain, he thought. A neat addition to his growing estate.

He did not notice the way the room exhaled when he won, as if it had been waiting for someone else to take the burden.

A Plantation That Looked Like a Portrait

Waverly Plantation appeared the way plantations were meant to appear to outsiders: white columns, wide porch, land stretching into the distance like the promise of permanence. It had the self-importance of a family portrait—clean edges, careful framing, no mention of what it cost to keep the picture intact.

Thomas was proud of it.

He walked the grounds like a man auditioning for history. He spoke to visitors about yield and improvement, about discipline and order. He believed power was simple: ownership, enforcement, and the ability to sleep without questioning how the day was paid for.

The overseer, Hutchkins, ran the work with tight rules and a colder temperament. He sorted people by usefulness and weakness, as though human beings were grain to be stored or discarded.

When he reached Celia, he hesitated.

Not out of kindness. Out of the kind of unease a man feels when he realizes he doesn’t understand what he’s looking at.

Thomas placed her in the old infirmary cabin. He told himself it was practical—close enough to monitor, far enough to keep contained. He believed he was making decisions.

He did not yet understand that he had brought something to Waverly that could not be managed by distance.

The Warning Nobody Wanted to Give

That evening, a neighbor arrived with a bottle in his hand and caution in his voice.

Josiah Crenshaw had the manner of a man who knew how to soften bad news without changing its meaning. He didn’t waste time on pleasantries. He asked Thomas if the new woman had a past.

Thomas laughed like a man hearing superstition.

Crenshaw didn’t laugh back.

He told Thomas about another property, an estate whose name people avoided in conversation, like saying it aloud might invite something inside. Rumors had followed a chain of losses there—illness, accidents, misfortune that seemed to arrive in clusters. People talked about patterns the way they talk about storms: not accusing the sky of intention, but refusing to stand outside when the air turns strange.

Crenshaw didn’t call Celia dangerous. He called the situation unwise.

“The kind of trouble that doesn’t announce itself,” he said, “but keeps showing up.”

Thomas dismissed him with a smile that didn’t reach his eyes. Pride made him careless. Pride made him eager to prove he wasn’t the sort of man who feared whispers.

That night, after Crenshaw left, Thomas went to the infirmary cabin anyway.

Some rooms change the temperature of your thoughts. The cabin smelled clean and bitter—herbs drying, water boiled, tools arranged with care. It was not a place of chaos. It was a place of preparation.

Celia rose when he entered. Her movements were controlled, her gaze direct but not defiant.

He asked about her skills, expecting gratitude.

She answered plainly, as if the truth did not require decoration.

Thomas asked about rumors, trying to sound casual.

Celia didn’t argue. She didn’t plead. She said something that felt less like a defense and more like a warning delivered without heat.

“The world keeps its own ledger,” she said.

Thomas returned to his house and tried to sleep, but he couldn’t. It wasn’t fear in the dramatic sense. It was a discomfort deeper than that—the feeling that he had stepped into a room where the rules had changed, and he hadn’t been given the new script.

When Crisis Arrived, Authority Failed

By October, a storm battered the region hard enough to make Waverly look less like a portrait and more like a fragile structure pretending to be permanent. Roofs tore. Fields flooded. The neatness Thomas loved was stripped away in a single night.

Then sickness moved through the quarters.

It didn’t care about Thomas’s pride. It didn’t respect his oversight. It spread with the blunt logic of circumstance, taking down the strong and the young without negotiation. A doctor came from Savannah with polished confidence and predictable advice, but his methods brought little relief.

When panic rises, people cling to whatever works.

Thomas found Celia moving through the makeshift ward with a steadiness that made the rest of the house look unprepared. She didn’t speak loudly. She didn’t demand attention. She simply worked—organizing, cleaning, separating the ill, insisting on basic steps that felt obvious in hindsight and revolutionary in the moment.

Thomas attempted to command her.

She responded with knowledge instead of obedience.

There is a difference between power and competence. Thomas had always assumed they were the same. Watching Celia, he realized they weren’t.

He gave her permission because he wanted results, not because he suddenly became virtuous. But the outcome challenged him anyway. The sick began to improve. The panic loosened. Life returned, not because Thomas had controlled it, but because Celia had understood what needed to be done.

Word traveled fast.

Soon people arrived from neighboring properties with fevers and injuries and desperate requests. Thomas found himself profiting from the work of the woman he had purchased as property. He told himself it was practical. He told himself it was business.

Yet something about the arrangement began to feel like standing too close to a fire you didn’t start.

The Signs People Choose to See

The first symbol appeared near the infirmary cabin—something painted where it would not be missed. A mark with a handprint at its center.

Thomas ordered it washed away.

But paint is never the point. The point is what people believe a mark means.

Whispers returned. Some said the symbol was a warning. Others said it was protection. The truth didn’t matter as much as the fact that the plantation was beginning to develop a second language—one Thomas didn’t control.

He noticed women visiting Celia’s garden.

He noticed how they stood differently afterward—shoulders set, eyes clearer, voices steadier. Not rebellious in a loud way, but changed in the quiet way that makes authority nervous.

A network was forming, built on care, knowledge, and mutual reliance. It did not ask Thomas’s permission. It did not require his approval.

That was what frightened him most.

The Ledger He Couldn’t Ignore

One winter morning, driven by suspicion, Thomas entered Celia’s cabin while she was away. He expected to find something dramatic—a weapon, a threat, proof of danger that would justify his fear.

What he found instead were notebooks.

Notes about remedies, illnesses, and patterns of recovery. Lists of what worked, what didn’t, what to watch for. But between the practical pages were lines that read like a private philosophy—words about balance, consequence, and what people owe one another when harm has been done.

Not an instruction manual for violence. Not a confession. A worldview.

When Celia returned and saw the look on his face, she didn’t panic. She didn’t plead. She simply spoke as if the truth was already seated in the room.

“You’ve been living off a system that calls cruelty normal,” she said. “And now you’re surprised that normal has consequences.”

Thomas tried to argue. He tried to call it superstition, bad luck, coincidence.

Celia didn’t accept any of those words.

She talked about a daughter lost—about grief that never found justice. She spoke of a world where the powerful rarely pay and the vulnerable carry the cost. She did not ask Thomas to feel sorry. She did not ask him to forgive her, or to excuse what he feared.

She asked him to look at himself without the comfort of denial.

For Thomas, that was the true punishment.

A Different Kind of Ending

By spring, Thomas had changed in small ways that mattered more than grand declarations. He began using names instead of numbers. He started listening before he spoke. He stopped confusing obedience for peace.

Was he redeemed? The story does not claim that. Redemption is a clean word history rarely earns.

But he did something that cut against his own pride. He filed papers that recognized Celia as free in the only language the system respected.

When he handed her the documents, he expected gratitude.

Celia took them calmly.

Then she did something Thomas didn’t anticipate: she stayed.

Not because she owed him anything. Not because she believed the place was hers. But because people depended on her, and she had decided long ago that survival without purpose was another kind of captivity.

Waverly became known for its healer.

Some called her a miracle. Some called her a curse.

Most people didn’t know what to call a woman who refused to be reduced to the role they needed.

And Thomas—standing on his porch in the evenings, watching the river move like time itself—learned a truth that frightened him more than any rumor ever could:

A ledger exists whether or not you acknowledge it.

Every benefit carries a cost.

Every silence has weight.

Every system comes due.

The story ends the way legends often do—not with fireworks, but with a quiet warning.

If you build a life on the suffering of others, you can decorate it with columns and paint, you can call it tradition, you can write it into law.

But you cannot outrun what the world records.

Not forever.