On the high moors of northern England, where wind bends grass flat against the earth and winters seem endless, there once stood a small stone farmhouse that time appeared to have forgotten. Smoke rose faintly from its chimney, and inside lived a woman whose life would eventually move an entire nation. Her name was Hannah Hauxwell, and for decades she lived alone in conditions that most people could scarcely imagine, not as a symbol, not as a protest, but simply because it was the only life she knew.

When Britain finally discovered her story in the early 1970s, the reaction was not shock alone, but recognition. In Hannah’s quiet endurance, people saw something rare and deeply human. Her life became a lens through which myth, culture, and science could all be explored, revealing why her story continues to resonate long after the cameras stopped rolling.

A Life Shaped by Landscape

Hannah Hauxwell was born in 1926 at Low Birk Hatt Farm, more than 1,100 feet above sea level in the Yorkshire Pennines. The land itself was formidable. Winters arrived early and lingered long. Snow could isolate the valley for weeks, and the wind carried a force that shaped both buildings and people.

Her family had farmed the land for generations, and from an early age Hannah learned that survival depended on routine, resilience, and respect for nature. There were no roads close by, no electricity, and no running water. Daily life revolved around physical work and careful use of limited resources.

This environment was not chosen for romance or simplicity. It was inherited, and it demanded everything from those who remained.

Choosing to Stay When Others Were Gone

By her early thirties, Hannah faced a turning point. One by one, her closest family members were gone, leaving her alone on the farm. At an age when many people are building new lives elsewhere, she was confronted with a stark choice: leave the land or stay and keep it alive.

She stayed.

Not because it was easy, and not because she believed herself especially strong. She stayed because the farm was home, and leaving felt unimaginable. In cultural storytelling, such decisions are often framed as heroic. Hannah never saw it that way. For her, it was simply what had to be done.

This quiet acceptance would become one of the defining features of her public image years later.

Life Without Modern Comforts

For decades, Hannah lived without electricity, without running water, and without nearby neighbors. A single coal fire provided warmth, though in winter it struggled against thick stone walls. Ice formed inside the house. Water froze in buckets. Washing required collecting water from a spring, even when the ground was hard with frost.

Her income was modest, barely covering essentials. Meals were simple and repetitive. Clothing was repaired rather than replaced. When snow closed the valley, there was no phone or radio to connect her to the outside world.

Yet when asked about these conditions, Hannah never dramatized them. “I manage,” she once said. “You just get on with it.” That phrase, so understated, would come to define how many people understood her character.

The Documentary That Changed Everything

In 1972, filmmaker Barry Cockcroft arrived at Low Birk Hatt Farm intending to document rural hardship. What he found was something far more compelling. His film, Too Long a Winter, aired in January 1973 and introduced Hannah to more than twenty million viewers.

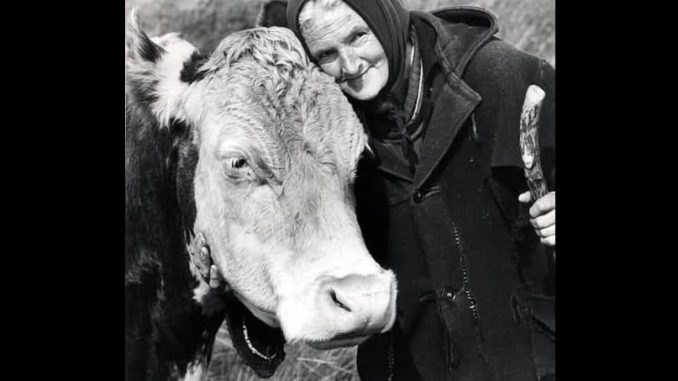

Audiences were struck not only by her living conditions, but by her manner. There were no complaints, no bitterness. She spoke softly, often with a gentle smile, as she went about her daily tasks. Feeding cattle in harsh weather, eating by firelight, and speaking plainly about life became powerful images of quiet endurance.

The documentary touched a nerve. Viewers saw in Hannah a part of Britain that felt forgotten, and a kind of strength that seemed increasingly rare.

Cultural Meaning and National Reflection

Hannah Hauxwell quickly became more than an individual story. She was seen as a symbol of rural endurance, a living connection to an older England shaped by land rather than technology. Letters poured in from across the country. People sent practical help, warm clothing, and heartfelt messages of admiration.

Culturally, her story challenged assumptions about progress. In a modern nation, how could someone live this way, unnoticed, for so long? Hannah did not accuse or demand. Her existence simply invited reflection.

In folklore and national identity, Britain has long valued stoicism and quiet perseverance. Hannah seemed to embody those traits without effort or intention, which made her story feel authentic rather than staged.

Scientific Perspectives on Isolation and Resilience

From a scientific viewpoint, Hannah’s life offers insight into human adaptability. Research in psychology and sociology suggests that people raised in stable, familiar environments often develop resilience through routine and purpose. Hannah’s days were structured by necessity. Animals needed care. Seasons dictated tasks. This predictability may have supported emotional stability despite physical hardship.

Studies on solitude also distinguish between loneliness and aloneness. Hannah herself articulated this difference, noting that she did not feel lonely, only alone at times. This aligns with research showing that meaningful work and a sense of belonging, even to land rather than people, can mitigate the negative effects of isolation.

Physiologically, living in cold environments requires adaptation as well. The human body can adjust to lower temperatures over time, particularly when exposure is gradual and consistent. While such conditions are not ideal, they illustrate the remarkable flexibility of human biology when combined with routine and necessity.

When the Nation Reached Back

After the documentary, practical changes followed. Electricity was installed at Low Birk Hatt Farm, something Hannah had lived without for nearly five decades. When she first switched on a light, she famously described it as “bringing the sun inside.”

Even then, she did not dramatically alter her lifestyle. She continued her routines, tended her animals, and lived simply. Attention embarrassed her. She insisted she had done nothing special.

Follow-up documentaries over the years allowed viewers to watch her age, reinforcing a sense of shared connection. Each appearance renewed public affection and respect.

A New Chapter Later in Life

By the late 1980s, the physical demands of farming became too much. In 1988, Hannah made the difficult decision to leave Low Birk Hatt and move to a cottage in Cotherstone, several miles away. For the first time, she experienced central heating, running water, and everyday comforts.

Her transition became news once again. Many saw it as the closing of an era, the end of the “last hill farmer” lifestyle. Hannah herself expressed gratitude for warmth and ease, while remaining characteristically modest about the attention.

In later years, she traveled, met public figures, and experienced places she had never imagined seeing. Fame never altered her manner. “I’m just Hannah,” she would say, grounding every extraordinary experience in humility.

Legacy Without Intention

Hannah Hauxwell never set out to inspire. Her life was not curated or designed to make a statement. That is precisely why it continues to matter. She showed that dignity does not require comfort, and that strength does not require recognition.

Her story endures because it speaks to universal questions. How much do we truly need? What does resilience look like when no one is watching? And how many lives, quietly lived, pass unnoticed until someone takes the time to look?

A Reflection on Human Curiosity and Meaning

Our fascination with Hannah Hauxwell reveals something essential about human curiosity. We are drawn not only to innovation and speed, but to endurance and simplicity. We look for meaning in lives that challenge our assumptions and remind us of forgotten possibilities.

Science helps us understand how Hannah survived. Culture helps us understand why we care. Together, they show that extraordinary stories do not always come from extraordinary intentions. Sometimes, they come from ordinary people who keep going, day after day, without applause.

Hannah was there all along, carrying water through snow, tending animals in silence, unseen and uncelebrated. When the world finally noticed, it recognized something enduring and profoundly human.

Sources

BBC Archive. Too Long a Winter documentary background.

British Film Institute. Rural life and documentary history in Britain.

University of York. Research on rural isolation and resilience.

Psychological Science Journal. Studies on solitude, purpose, and well-being.