The Iron Box in the Wall

In October 1896, crews demolishing a long-abandoned warehouse in Louisville, Kentucky uncovered something that wouldn’t be widely understood for another seventy-two years.

Behind a fake brick partition—sealed, reinforced, and left to disappear into time—they found a heavy iron box. It carried no stamp, no initials, no identifying marks. Only rusted hinges and a lock that had to be forced open.

Inside lay twenty-three documents.

There were handwritten letters, baptism records, property papers, a personal journal, and one item that should not have existed at all: a marriage certificate dated March 17, 1841.

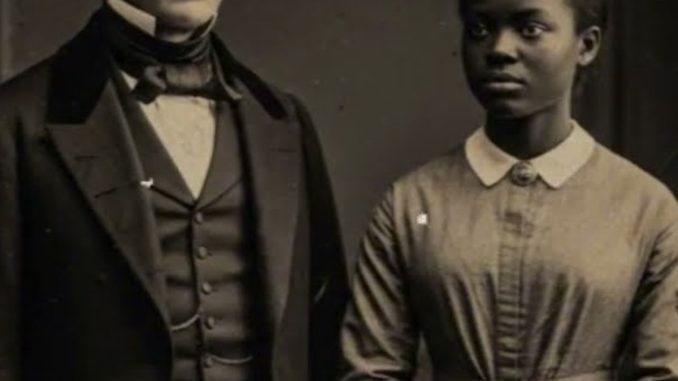

The groom was Philip Perry, a sitting United States Senator from Missouri.

The bride was Harriet Preston, a woman the law classified at that time as his property.

Missouri law in 1841 explicitly barred marriage between white people and people of African descent. Breaking that line could mean imprisonment, financial collapse, and political ruin.

Yet the certificate carried their signatures—along with a minister’s seal and the witnessed signatures of four other people.

This wasn’t rumor.

Not secondhand talk.

Not folklore.

It was documentation.

A City Built on Contradiction

To understand how such a record could exist, researchers had to rewind to St. Louis in the late 1830s—a city balanced uneasily between written law and practical convenience.

By 1839, St. Louis had surged from frontier settlement to booming commercial hub. Steamboats packed the Mississippi waterfront. Cotton, tobacco, furs, and whiskey moved through warehouses stacked barrel-high. Money traveled quickly. Enforcement did not.

Slavery was everywhere—and rarely discussed openly.

Enslaved people built docks, hauled cargo, ran households, cooked meals, cleaned offices, and maintained the outward image of prosperity. Missouri’s slave code made them legally “invisible,” even as the economy depended on their work.

Justice in St. Louis was not impartial.

It was adjusted.

Who you were mattered more than what you did.

Senator Philip Perry: A Man of the System

Philip Perry arrived in St. Louis in 1823 with ambition, legal training, and a gift for aligning himself with power. By 1836, he had secured a seat in the United States Senate.

He was not a loud extremist. He presented himself as a moderate—often the most effective kind of slavery defender. He argued slavery was constitutional, economically necessary, and likely to fade away “naturally” without interference.

He was respected.

He was cautious.

He was successful.

Publicly, he fit the racial and legal order of his time perfectly.

Privately, he would collide with it.

The Purchase

On April 9, 1838, Perry attended a slave auction in St. Louis.

Among those sold was an eighteen-year-old woman from Virginia: Harriet Preston.

Accounts describe her as unusually tall, literate, and skilled in bookkeeping and household organization—educated before Virginia intensified restrictions around literacy.

Her price was high: $750—reflecting her capability and intellect as much as her labor value.

Perry bought her not as a field worker, and not with a public explanation that suggested anything scandalous, but as a household manager.

At least, that was the official framing.

The Quiet Center of the House

For the first year, Harriet did exactly what Perry’s household demanded.

She ran the home with an efficiency that made her nearly unseen. She kept accounts, supervised staff, handled correspondence, and kept the senator’s public routine smooth.

She lived inside the house, not behind it.

She had access to books.

She was trusted.

Perry’s wife, Louise, gave her little attention. That indifference created space.

When Louise traveled to New Orleans in late 1839 and stayed for months, the household’s rhythm changed.

Performance gave way to quiet.

When Conversation Becomes Recognition

The shift did not begin with attraction.

It began with talk.

One night, Perry worked late on a political speech and struggled to shape an argument about federal restraint. Harriet—bringing coffee—offered a quotation from Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws.

Perry stopped cold.

She didn’t just recognize the passage.

She understood how it applied.

That night they spoke for an hour. Then two. Then the conversations continued across the winter.

Politics. Law. Philosophy. History.

What Harriet revealed wasn’t borrowed intelligence—it was original thought.

For a man whose career depended on the premise that people like her were inherently lesser, the implication was destabilizing.

The Relationship That Had No Name

By early 1840, their relationship crossed a line neither could ignore.

There were no dramatic proclamations. No single moment of open rebellion.

Just accumulation.

Proximity. Trust. Shared ideas. Mutual recognition.

Missouri law had no category for what existed between them. It was neither sanctioned nor protected. It couldn’t be named without risk.

And that frightened them both.

The Letter That Changed Everything

In March 1840, Perry received a letter from Louise in New Orleans.

She would not return.

The marriage, she wrote, had always been a business arrangement. It had served its purpose. She intended to remain in Louisiana with the children.

She wanted formal separation and financial support—nothing more.

For Perry, that letter removed the last external restraint.

For Harriet, it sharpened the danger.

The Question No Law Could Answer

They faced a decision.

Continue as they were—quiet, illegal, undefined.

Or acknowledge what already existed.

Harriet understood the risk more clearly than Perry ever could.

If discovered, she could be sold further south.

Separated. Disappeared.

Her future erased.

Yet she wanted more than secrecy.

She wanted commitment.

The Minister Across the River

Perry crossed into Illinois, where Missouri’s reach did not extend as cleanly.

There he contacted Jonathan Wells, a Methodist minister known discreetly for abolitionist leanings.

The request was extraordinary:

A marriage ceremony.

Between a white senator and an enslaved woman.

Documented—yet never revealed.

Wells hesitated.

Then agreed, but only with conditions.

The ceremony would be private. Witnessed. Hidden. And never acknowledged unless a later society could survive the truth.

March 17, 1841

They crossed the Mississippi together.

Six people stood in a church basement in Alton, Illinois.

Scripture was read. Vows were exchanged. Rings were placed.

Philip Perry and Harriet Preston were pronounced husband and wife.

Legally impossible.

Spiritually undeniable.

They returned to Missouri that evening as master and enslaved woman.

But they understood themselves differently from that night forward.

A Child the Law Could Not Name

The first consequence of that hidden marriage arrived not as scandal, but as a paperwork problem.

In November 1842, Harriet gave birth to a daughter in St. Louis. The child was healthy and quiet. Household staff were dismissed for the week. A midwife was paid to forget what she witnessed.

Then came the question no one could answer without igniting disaster:

What was the child’s legal status?

Under Missouri law, a child followed the condition of the mother. Harriet was enslaved. Therefore, the child—regardless of the father—was enslaved.

But Philip Perry was not only the biological father.

He was also the husband.

That reality created a legal contradiction no court wanted to touch.

If Perry acknowledged the child publicly, he admitted to a criminal marriage and an illegal interracial relationship. If he refused, his daughter remained property—subject to sale, inheritance, or seizure.

For the first time, Perry confronted a system he couldn’t manage with influence.

The Illusion Begins to Fracture

Within weeks, rumors began to circulate.

A senator who dismissed his staff.

An enslaved woman no longer appearing at public gatherings.

A child whose existence was carefully obscured.

Political rivals noticed.

In private correspondence recovered decades later, one opponent wrote:

“There is something unspeakably dangerous in Perry’s domestic affairs. He would do well to retire.”

Pressure came from both moral suspicion and political calculation.

A quiet committee requested Perry’s presence in Washington earlier than expected. He was advised—informally—that continued service might become “untenable.”

This was not justice.

It was containment.

The Law Moves Closer

In early 1843, a clerk in the St. Louis Recorder’s Office flagged an irregularity: Harriet Preston’s purchase record had never been updated. On paper, she remained Perry’s property—yet there was no labor valuation update, no resale listing, no tax adjustment.

She had become administratively visible.

And in slave states, paperwork functioned as surveillance. Anything that failed to move “normally” drew attention.

Perry understood what was approaching.

Discovery would not end in an open trial.

It would end in erasure.

The Decision to Disappear

The solution would not come through courts.

It would come through leaving.

In April 1843, Perry resigned his Senate seat, citing “persistent illness.” Newspapers printed polite notices. No formal investigation followed.

Within weeks, property holdings were shifted into trusts. Accounts were closed. Associates were paid to forget details.

The household dissolved.

And Philip Perry vanished.

Officially, he traveled south for treatment.

Unofficially, he crossed the Mississippi with Harriet and their child—never to return.

Mexico: Where the Law Failed to Follow

They settled briefly in Coahuila y Tejas, then under Mexican authority.

Mexico had abolished slavery in 1829.

There, Harriet was not property.

The child was not owned.

The marriage was not a crime.

A Catholic parish record in Saltillo lists a baptism in July 1843 for a child named Elena Perry—parents recorded as Philip and Harrieta, married.

No race label appears.

For the first time, the family existed on paper without contradiction.

But safety came with loss.

Perry could not return to American politics. His name faded from public life. Former allies never spoke of him again.

He was not formally punished.

He was removed.

Why the Records Were Hidden

The iron box found in Louisville wasn’t casual storage.

It was deliberate burial.

After Perry died in 1861, Harriet lived nearly a decade longer. Before her death, she arranged for the family’s documents to be sealed and moved north—far from Missouri courts and far from the volatility of Reconstruction-era politics.

Why hide them?

Because revealing the marriage would not have “corrected” the record.

It would have endangered descendants.

Even after emancipation, many states continued to outlaw interracial marriage for generations. Exposure could still carry legal and social consequences.

Silence functioned as protection.

The Historian’s Dilemma

When the documents were finally catalogued in the 1960s, archivists argued over two questions: were they authentic—and was it ethical to make them public?

The papers forced an uncomfortable set of problems:

If a marriage existed but could not be named, was it real?

If a woman “consented” inside a system that denied her legal autonomy, what did consent mean?

If affection existed inside exploitation, did that lessen the wrong—or sharpen it?

There were no clean answers.

Reframing the Case

Modern historians often treat the Perry–Preston marriage as a boundary case—neither a story of moral progress nor a tale of benevolent exception, but a harsh exposure of contradiction.

Philip Perry benefited from a system that dehumanized Harriet Preston.

Harriet Preston navigated that system with intelligence, risk, and agency—but never with equality.

Both realities exist at the same time.

This was not a romance that redeemed slavery.

It was a relationship that revealed slavery’s inescapable harm—even in its most intimate spaces.

Why This Case Matters Now

This story endured not because it was truly one-of-a-kind.

It endured because it was representative.

Thousands of relationships existed in similar shadows—undocumented, unacknowledged, unpreserved. Most left no paper trail.

This one survived through foresight, silence, and the stubborn accident of time.

And because it survived, it forces a reckoning that modern history often tries to soften:

Legality is not morality.

Intimacy does not erase power.

Love inside injustice cannot be understood without naming the injustice first.

The Final Record

Today, the marriage certificate is archived under restricted access—not to protect reputations, but to preserve context and prevent misuse.

It is catalogued as:

“A legal impossibility that nonetheless occurred.”

The phrasing is exact.

The law insisted it could not exist.

The people involved lived otherwise.

And history—slow, uneasy, and unavoidable—was compelled to hold both truths at once.