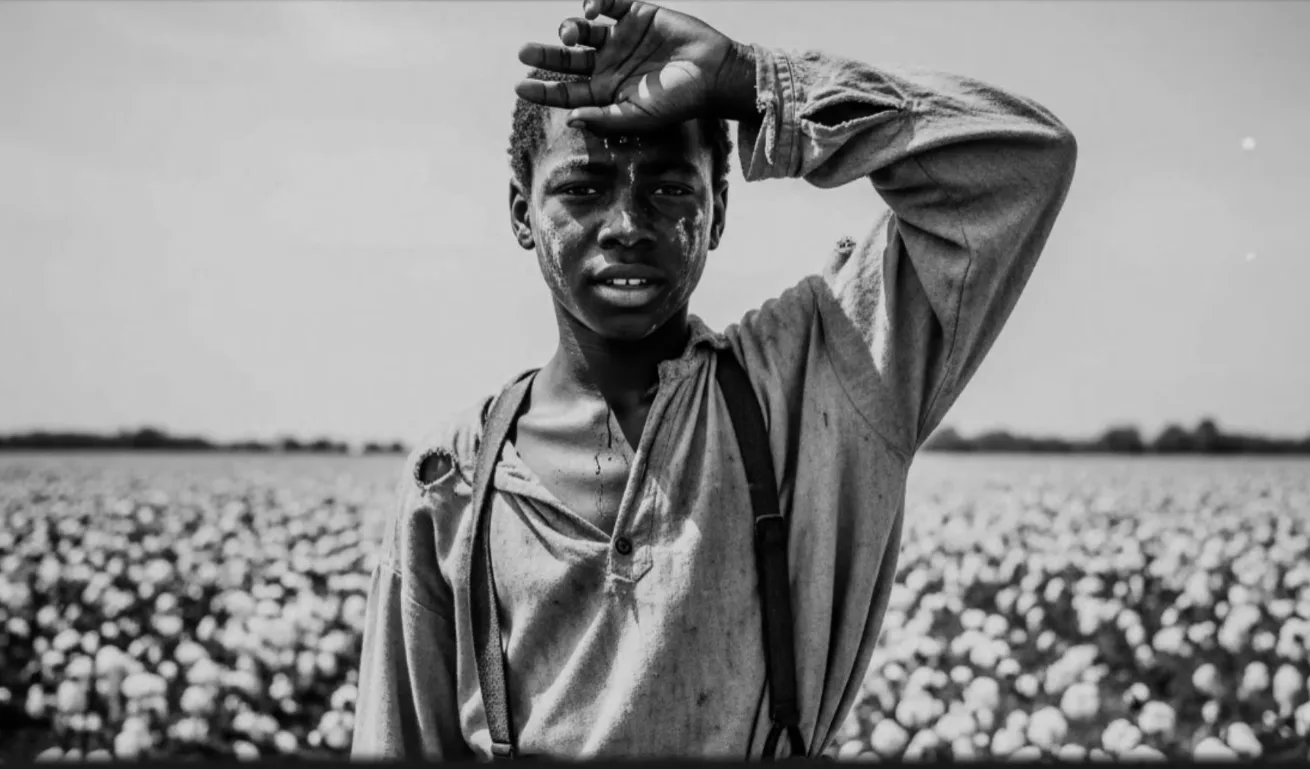

Wilkinson County, Mississippi, summer of 1851.

Dawn had barely broken over Meadowbrook Plantation when a sound unlike any other cut through the cotton fields. It was not the crack of a whip or the call of an overseer. It was the sharp, sudden cry of pain — the kind that made even the most hardened workers pause, if only for a heartbeat.

The cry came from Thomas, a boy of ten.

He had been sent into the fields early, as children often were, tasked with clearing fallen plants and loose debris between the rows. The work was tedious but familiar. What was not familiar — what no child could prepare for — was the hidden danger waiting beneath the leaves. A snake, startled and unseen, struck without warning.

Thomas collapsed where he stood.

At first, the pain confused him. Then it overwhelmed him. He cried out again, but his voice faded quickly, swallowed by heat and shock. The marks on his leg darkened, swelling as his small body struggled to understand what had happened.

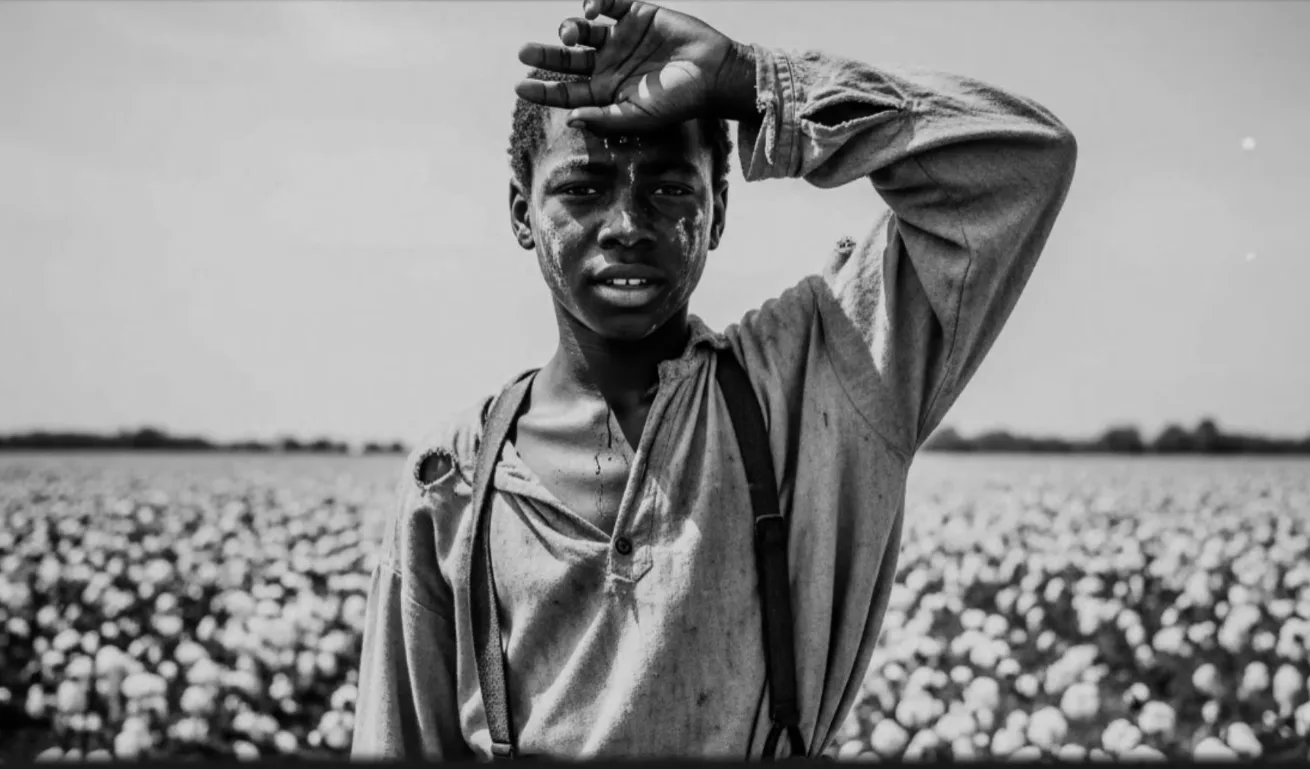

The other enslaved workers heard him.

They knew what a snakebite meant. In that region, in that era, such an injury often carried a grim certainty. They also knew the rules. No one left their row without permission. No one stopped working unless ordered. No one intervened without consequence.

So they stood still.

Not because they did not care, but because caring openly could cost them their lives.

Minutes later, the overseer arrived.

Samuel Hartwick was known across the plantation for his efficiency and lack of sentiment. He dismounted from his horse and examined the boy briefly, the way one might assess damaged equipment. His decision was made quickly. Calling a doctor would cost money. Medicine was not guaranteed to work. A child, in his accounting, was replaceable.

Hartwick announced that no help would be given.

If the boy survived, it would be by chance alone. If he died, the work would continue.

Then he turned back toward the main house, leaving Thomas in the dirt beneath the rising sun.

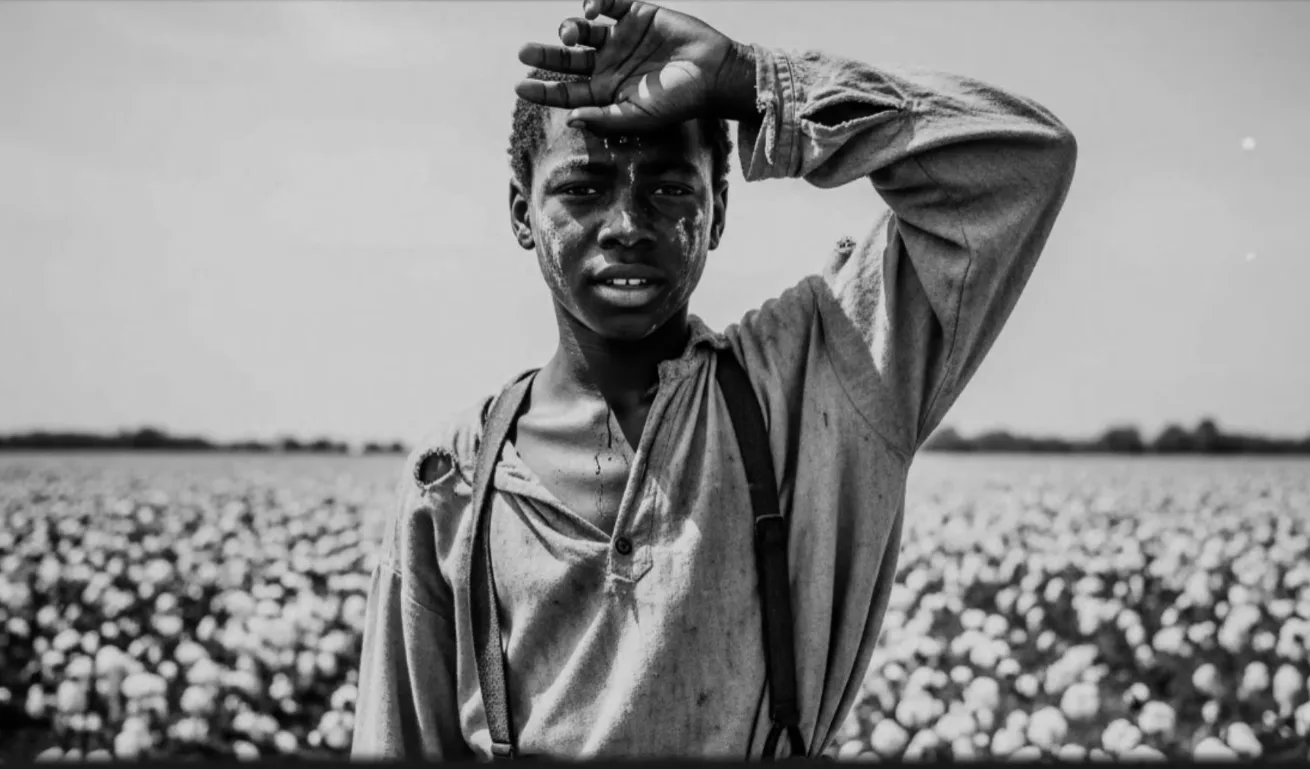

As the morning wore on, the heat intensified. The venom worked through the boy’s body, weakening him hour by hour. By midday, he barely moved. The field workers were ordered farther away so they would not be distracted by what everyone assumed was inevitable.

In the logic of the plantation, Thomas was already gone.

But the plantation was not the whole world.

From the kitchen window, Ruth had seen everything. She had lived more than fifty years under bondage and had learned the difference between recklessness and resolve. She did not rush. She waited. Waiting had kept her alive longer than most.

Ruth carried knowledge passed quietly through generations — remedies learned from elders who had survived long before doctors or written manuals ever reached them. Knowledge that was dismissed by white authorities but trusted deeply within the enslaved community.

When the house grew quiet and the overseer withdrew, Ruth moved.

She knelt beside Thomas, listening to his breathing, assessing his condition with practiced calm. Then she disappeared into the woods and returned with leaves, bark, and roots gathered quickly but deliberately. She worked silently, treating the wound, easing the fever, giving the boy’s body a chance to endure.

She did not stay long. To linger would be to risk discovery.

Others saw her actions.

No one spoke.

That night passed slowly. Then another morning came.

Against all expectations, Thomas still lived.

By the second day, his breathing steadied. By the third, the fever eased. Ruth understood the danger clearly now. The overseer believed the boy was dead. That belief protected Thomas — for the moment.

But it would not last.

If Thomas were found alive, the punishment would be severe, not only for him, but for anyone who had helped him. Survival, in this case, required something more than healing. It required disappearance.

Ruth gathered a small group she trusted — people who understood the cost of defiance. She spoke plainly. The boy could not remain. He would be sent away, quietly, permanently.

They would do something unthinkable.

They would let Thomas die in the eyes of the plantation.

A small coffin was constructed from scrap wood. A shallow grave was dug at the edge of the property. A simple marker was placed, bearing only a name. The enslaved community gathered in silence, singing softly, praying — mourning not only for a boy who lived, but for all the children who had not been spared.

The overseer attended briefly. He blamed the child for his own fate and left without a second glance.

The plantation believed the matter was finished.

That night, under cover of darkness, four figures moved through the fields. Thomas was wrapped in cloth, weak but conscious. Food was tucked against his chest. Directions were whispered repeatedly, so fear would not erase them.

North.

Always north.

They watched until he vanished into the trees, then returned to their places before dawn, carrying the weight of what they had done.

Thomas never returned.

Official records would list him as dead. Meadowbrook Plantation would never speak his name again. But within the quiet memory of the enslaved community, his survival became something more than a story.

It became proof.

Proof that compassion could exist even where cruelty ruled. Proof that knowledge, patience, and trust could outmatch violence. Proof that freedom sometimes began not with escape, but with being declared gone.

Years later, long after Meadowbrook Plantation itself faded into history, whispers of the boy endured. Some said he reached free soil. Others said he learned to read, to write, to live without fear. No one claimed certainty.

What mattered was this: a child who was left to die had been chosen to live.

In a system designed to erase humanity, a quiet act of courage rewrote one life’s ending.

And that, in itself, was a miracle.