This 1887 Photograph of a Father and Son Holding Hands Seemed Ordinary — Until History Caught Up With It

At first, the photograph appeared to be exactly what it claimed to be: a final family portrait taken inside Newgate Prison in the late Victorian era.

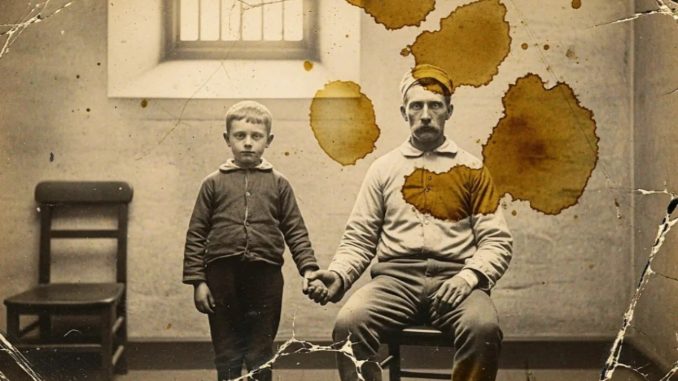

The image shows a seated man and a young boy standing close beside him. Their hands are clasped. Both look straight toward the camera. The room is bare, the lighting stark, the composition carefully arranged by a prison photographer following official rules.

For decades, museum catalogues described it as a routine record of a condemned prisoner’s last visit with family. Sad, certainly—but not unusual for its time.

What no one realized for more than a century was that this single photograph quietly preserved evidence that would later overturn a death sentence.

A Brief Moment, Carefully Documented

The photograph was taken on March 18, 1887, during a tightly regulated visit granted to prisoner Michael O’Conor. Prison rules allowed one short meeting with immediate family and, on rare occasions, a single photograph under guard supervision.

O’Conor sat in a wooden chair. His ten-year-old son, Daniel, stood beside him. At the instruction of guards, their hands were joined. The photographer adjusted the camera and asked them not to move for several seconds while the plate was exposed.

When the shutter closed, the visit ended.

Three days later, Michael O’Conor was executed.

Daniel kept the photograph for the rest of his life.

The Man Behind the Prison Number

Michael O’Conor was not born into crime. He was born in County Cork in 1849, during the final years of the Irish Great Famine. As a child, he emigrated with his family to London, settling in Whitechapel among thousands of Irish laborers seeking work.

By adulthood, he had built a modest but stable life. He trained as a carpenter, opened a small workshop, married a seamstress named Ellen Murphy, and raised two children. They were not wealthy, but they were known as respectable and hardworking.

That stability collapsed in January 1887.

A Crime and a Convenient Suspect

On the evening of January 15, 1887, Lord Edmund Hartley—a wealthy landowner and Member of Parliament—was attacked in his carriage near Spitalfields. The assailant struck him and fled with a leather case containing cash and documents.

In statements to police, Hartley described his attacker as Irish and a tradesman. Within twenty-four hours, Michael O’Conor was arrested.

The case moved quickly. O’Conor’s profession matched the description. He had been working in the area that day. Most significantly, Hartley identified him during a lineup.

O’Conor denied involvement from the moment of his arrest. He stated he had completed a delivery earlier in the evening and returned home before the attack occurred. But his defense relied on uncertain recollections and circumstantial timing. His court-appointed barrister had little experience. The trial lasted three days. Jury deliberations took less than an hour.

The verdict was guilty.

Judgment in an Era of Assumptions

Victorian courts often treated class and ethnicity as indicators of guilt. The judge’s remarks reflected this bias, describing O’Conor as a representative of “dangerous tendencies” rather than weighing evidence with detachment.

O’Conor was sentenced to death.

His wife collapsed after the verdict and was unable to attend his final visit. Their daughter was deemed too young. Only Daniel, escorted by an aunt, was permitted to come.

Eight Seconds That Lasted a Century

The prison visit was brief. Father and son spoke about ordinary things—school lessons, home, Daniel’s younger sister. They avoided discussing the sentence until the photograph had been taken.

Afterward, Daniel asked his father a question that would stay with him for life: had he committed the crime?

Michael answered simply and directly that he had not. He swore his innocence without qualification.

Daniel believed him.

A Photograph Reexamined

For more than a hundred years, the image passed quietly through family hands before being donated to a criminal justice museum. It remained largely unexamined until a 21st-century digitization project allowed conservators to study it at extreme resolution.

When specialists enlarged the image, they noticed something previously invisible to the naked eye: a distinct impression on Michael O’Conor’s wrist.

It was not a bruise or shadow. It matched the pattern of a specific type of police manacle used only during initial arrest and transport—not during later incarceration at Newgate.

And it appeared recent at the time the photograph was taken.

Why That Detail Changed Everything

According to official records, O’Conor was arrested on January 16, the day after the assault. But the manacle mark suggested he had been restrained earlier—on the night of January 15 itself.

That discrepancy mattered.

If O’Conor had been detained earlier than stated, it would mean his alibi had been impossible to establish because he was already in custody when witnesses might have placed him elsewhere. It also raised questions about the identification procedure conducted while the victim was injured and disoriented.

Further archival research uncovered troubling confirmations: altered police logs, missing witness statements, and a private letter from a senior officer acknowledging that arrest times had been adjusted to “regularize” the case.

A Son’s Lifelong Effort

Daniel O’Conor spent his adult life pursuing justice. He became a journalist, focused on exposing wrongful convictions. He petitioned officials repeatedly to review his father’s case.

Every appeal failed.

Daniel died believing he had not done enough.

But the photograph he preserved did what petitions could not. It endured unchanged, waiting for tools capable of revealing what it held.

Official Recognition, Long Overdue

In 2019, historians presented their findings to government authorities. After review, the British government issued a posthumous pardon in 2020—133 years after Michael O’Conor’s execution.

The statement was brief and unequivocal: Michael O’Conor was innocent.

At a memorial event, his granddaughter placed flowers beneath a plaque bearing his name. For the family, the acknowledgment did not undo the past—but it restored truth to the record.

What the Image Teaches Us

Today, the photograph is displayed not as a relic of punishment, but as a lesson in evidence. It demonstrates how truth can persist in overlooked details, how technology can reopen closed histories, and how justice, though delayed, is not always lost.

Michael O’Conor held his son’s hand for eight seconds.

It took more than a century for the world to understand what those seconds contained.

But in the end, the photograph spoke—and history listened.