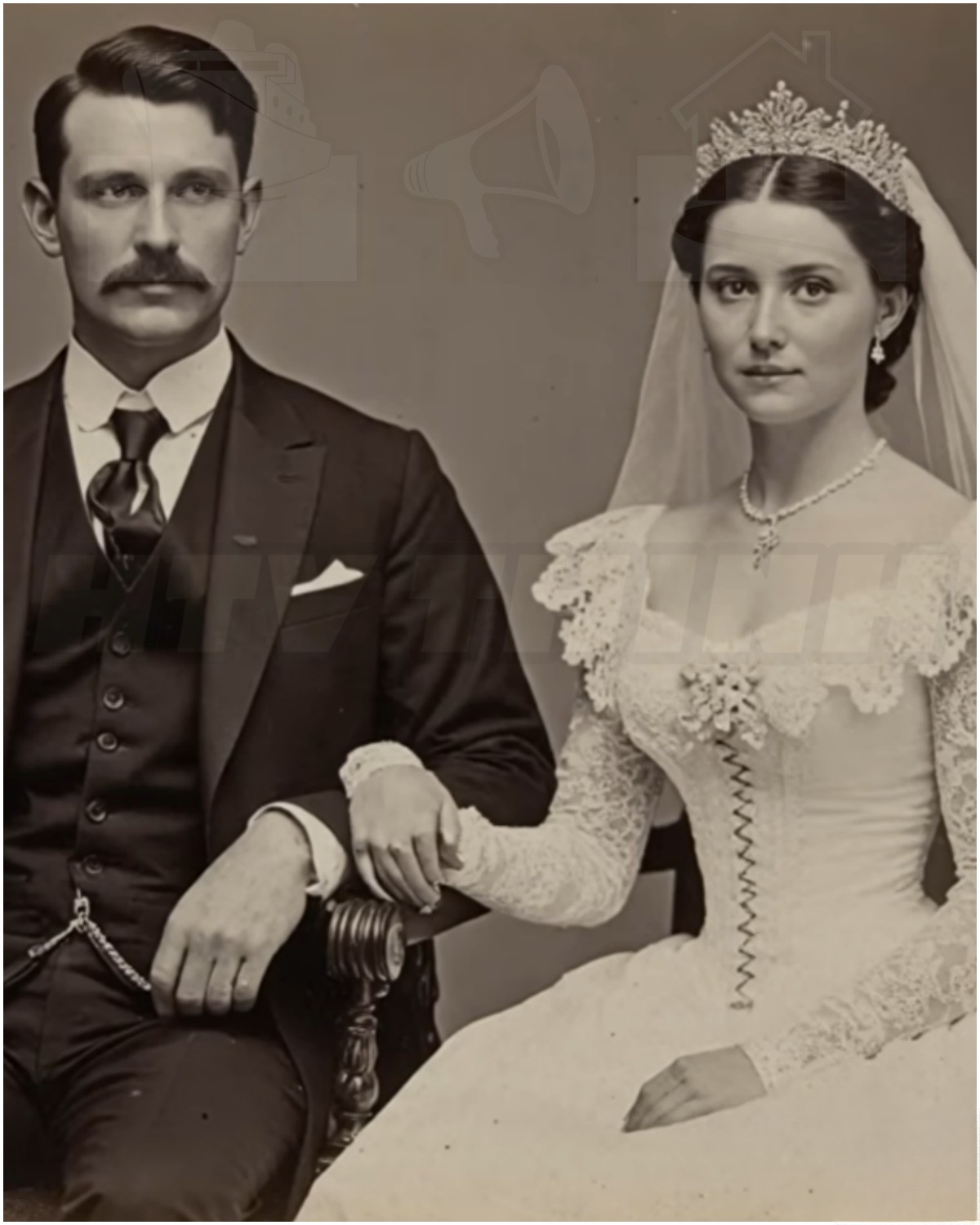

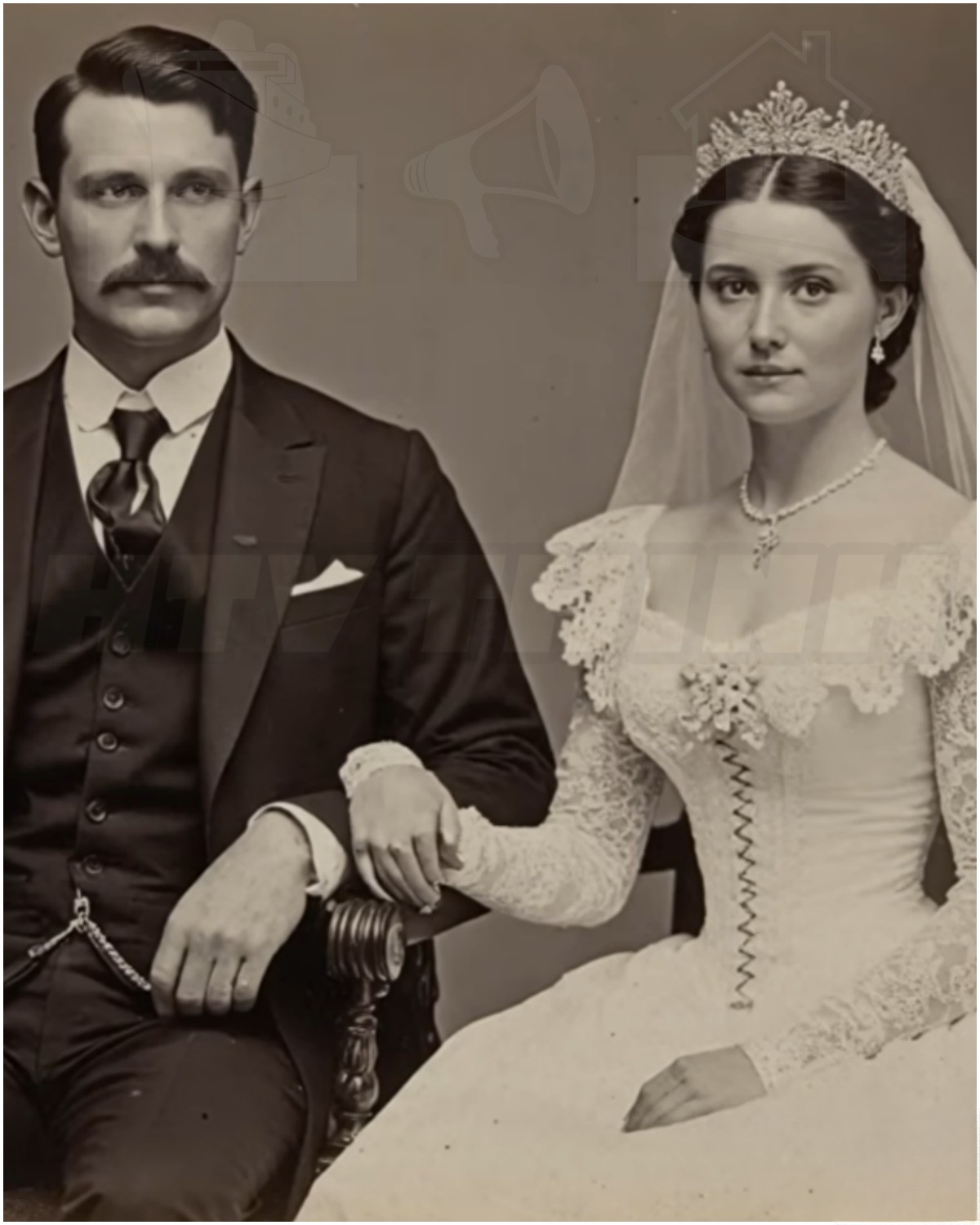

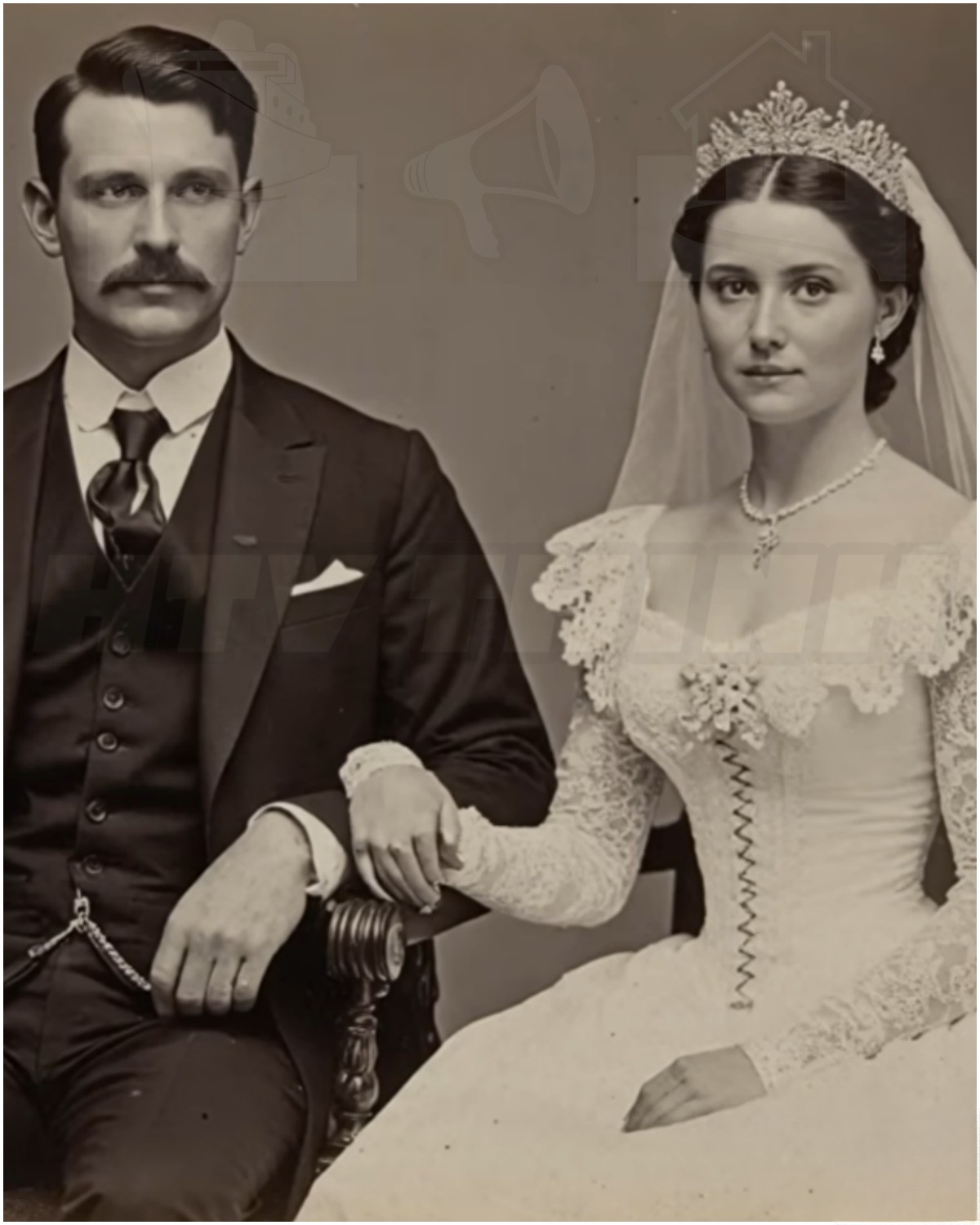

At first glance, the photograph looked unremarkable.

It arrived at a regional archive in a faded cardboard frame, lightly warped by time. A penciled note on the back read simply: 1899. Beneath it were two names written in careful cursive—Henry Walters and Lilian Moore.

For decades, the image had been cataloged as a standard late-Victorian wedding portrait. Sepia-toned. Carefully posed. A visual artifact of an era obsessed with order, propriety, and appearances.

Nothing about it seemed unusual.

Until someone looked closer.

A Familiar Image From a Familiar Era

Wedding portraits from the turn of the 20th century followed strict conventions. Photographers worked from scripts. Brides and grooms were positioned precisely, often corrected repeatedly before the shutter clicked. Exposure times were long, demanding absolute stillness.

Men sat. Women stood.

Men displayed confidence and authority. Women displayed composure and restraint.

This photograph followed those rules perfectly—almost too perfectly.

Henry Walters sat in a carved studio chair, dressed in a dark, well-tailored suit. His posture was relaxed but assured, one arm draped casually across the chair’s armrest, the other resting on his knee. He looked like a man accustomed to being obeyed.

Beside him stood Lilian Moore.

She wore a white dress with a fitted bodice and a carefully arranged veil. Her expression was neutral, almost serene, her gaze directed just past the camera as etiquette required. Everything about her presentation suggested compliance with expectation.

Everything except one thing.

The Detail No One Had Noticed

When the photograph was digitized for high-resolution archival review, an image analyst paused mid-scan.

Lilian’s left hand was partially concealed by the folds of her dress, just below her waistline. It was not resting naturally. It was not relaxed.

The fingers were bent at sharp, deliberate angles. The thumb pressed inward. The index finger extended slightly apart from the others. The remaining fingers curled tightly, held in visible tension.

This was not the hand of someone merely nervous about a camera.

It was being held in position.

The analyst adjusted contrast and magnification. The configuration became unmistakable.

This was not accidental.

Why the Hand Mattered

In Victorian portraiture, hands mattered. Manuals from the period devoted entire chapters to proper placement. A woman’s hands were expected to appear soft, ornamental, and calm—symbols of virtue and submission.

Tension was discouraged.

Deviation was corrected.

Holding an uncomfortable, unnatural hand position through a long photographic exposure required intention. It also required resolve.

The more historians compared the image to thousands of similar portraits, the clearer it became: this hand did not belong to the visual language of celebration.

It belonged to something else.

Consulting the Context

Historians specializing in late-19th-century social customs were brought in. Their focus immediately shifted away from the couple’s faces to the space between their bodies—and to that concealed hand.

Marriage in 1899 was not merely a personal union. It was a legal and economic transfer. Upon marriage, a woman’s independent legal identity was effectively absorbed into her husband’s. Property, income, residence, even personal correspondence often came under male control.

Consent, as understood today, was not the central concern.

What unsettled researchers was not just the hand itself, but what followed in the historical record.

Or rather, what didn’t.

A Sudden Absence

Henry Walters appeared frequently in municipal documents—property records, business filings, investment notices.

Lilian Moore did not.

There was no marriage certificate.

No church registry.

No census update listing her as a wife.

No death notice.

Within weeks of the photograph’s date, her name disappeared entirely from official documentation.

If the marriage had been legitimate, paperwork would exist.

If it had not, the photograph became something else altogether.

Not proof of union.

But proof of compliance.

A Hidden Language

The breakthrough came from an unexpected source: a women’s etiquette guide printed in 1897 for finishing schools and academies. Most of the book focused on posture, manners, and social conduct.

Near the back was a short, carefully worded section addressing what the author called “circumstances of personal peril.”

The language was indirect but unmistakable. It acknowledged that some women might find themselves under authority they could not openly resist. In such cases, the guide suggested discreet bodily signals—small gestures that could be held briefly, subtle enough to evade supervision but recognizable to those trained to see them.

One illustrated hand position matched the photograph exactly.

Thumb pressed inward.

Index finger extended.

Remaining fingers curled tight.

The printed meaning was clear.

I am being held against my will.

This was not a modern reinterpretation.

It was a period explanation.

Reconstructing the Story

Further archival research revealed that Lilian Moore had worked as a stenographer at a financial firm connected to railroad land speculation. Notes in company correspondence mentioned her attention to discrepancies. One memo described her as “asking unnecessary questions.”

Shortly afterward, Henry Walters appeared in records connected to the same network—not as a romantic partner, but as a “resolver,” a man whose role seemed to involve quietly removing complications.

Marriage solved many problems in that era.

No witnesses were required for a photograph.

No license was strictly necessary if the image itself could serve as implied legitimacy.

The portrait was paid for in advance by a third party linked to the same financial interests Lilian had been documenting.

It was not commissioned by family.

It was documentation.

The Photograph Reconsidered

When researchers returned to the image with this context, its meaning shifted.

Henry’s relaxed posture no longer suggested ease—it suggested vigilance.

Lilian’s calm expression no longer looked serene—it looked deliberate.

She had known this image might be the last public record of her existence.

Her resistance was not dramatic. It was precise.

She followed every instruction except one.

She refused to relax her hand.

Why It Matters Now

Lilian Moore left no diary. No letter. No personal testimony.

But she left something else.

A trace.

A signal embedded in plain sight, overlooked for more than a century because it required patience, context, and the willingness to question what looks “normal.”

Today, the photograph is no longer archived as a simple wedding portrait. It is studied as an example of coerced imagery and silent resistance within rigid social systems.

Students examine it.

Scholars enlarge it.

And the same detail continues to speak.

The hand.

The tension.

The refusal to fully comply.

It asks a quiet but unsettling question across time: how many other images have we misread because we never thought to look closely enough?

Sometimes the most important truths in historical photographs are not hidden in shadow.

They are placed deliberately, carefully, in plain sight.

Waiting for a future willing to notice.