Stories like the one often titled “The Black Mamba” circulate widely online because they speak to something deeper than historical detail. They are not records of specific events, but symbolic narratives—constructed to explore grief, moral reckoning, and the desire for justice in eras when justice was systematically denied.

To understand why this story resonates, it helps to approach it not as a literal account, but as a psychological and cultural allegory rooted in real historical conditions.

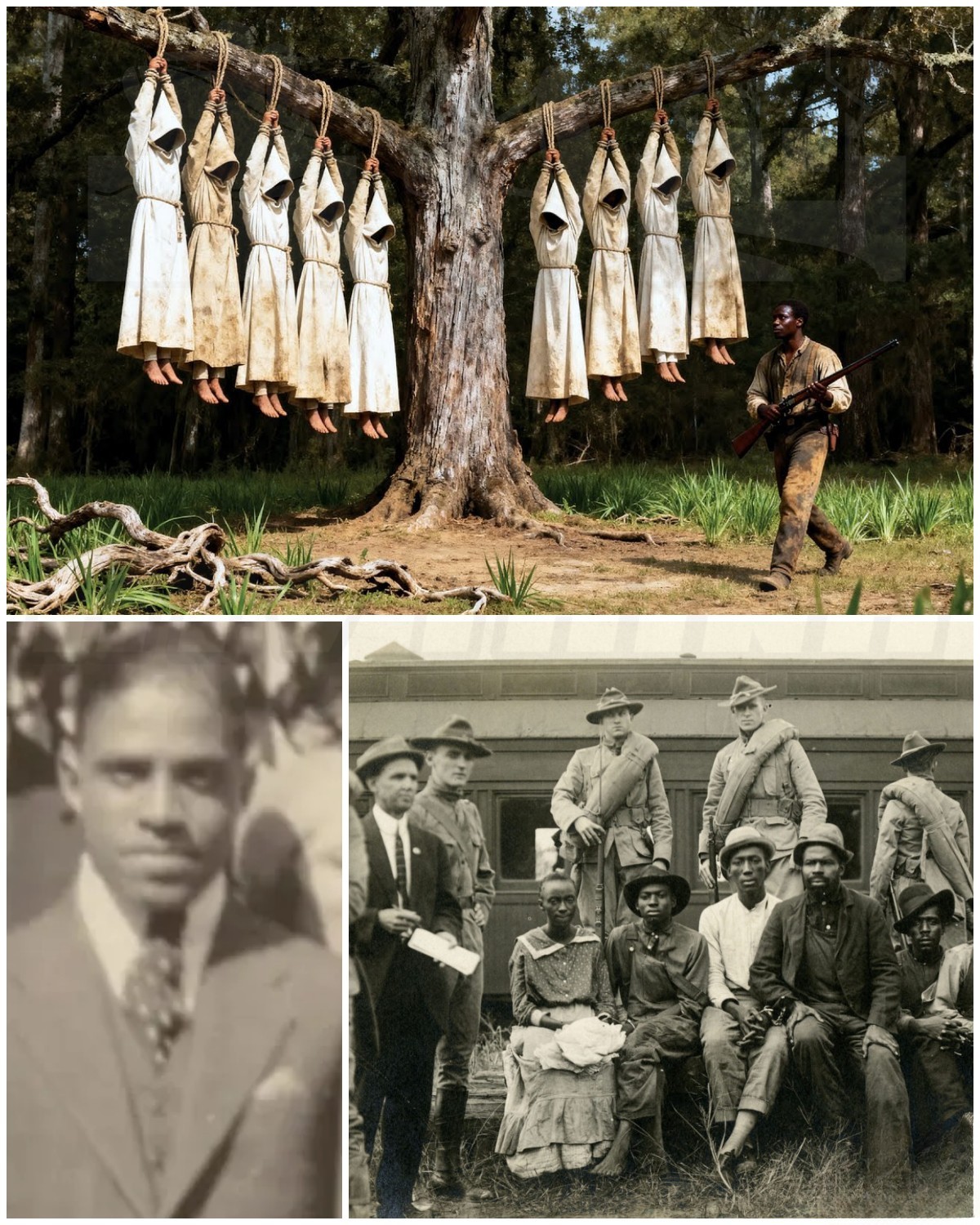

The setting evokes the post–World War II American South, a period marked by contradiction. Black veterans returned from fighting fascism abroad only to encounter racial terror at home. Lynching, intimidation, and organized white supremacist networks were still realities in many communities, often protected by silence or complicity within local institutions.

The protagonist, often named Ezekiel Turner and called “The Black Mamba,” represents a composite figure rather than a documented individual. He embodies the Black veteran who returns trained, disciplined, and changed—no longer willing to accept the old rules that demanded submission for survival.

What distinguishes this narrative from simpler revenge tales is its focus on psychological transformation rather than physical retaliation. The story frames Turner’s evolution as a shift from private grief to strategic clarity. His military experience is not portrayed as a license for violence, but as a lens through which he recognizes systems: hierarchy, coordination, fear, and myth-making.

In this framework, white supremacist groups are not portrayed as invincible forces, but as fragile networks sustained by secrecy, intimidation, and shared illusion. Their power depends less on strength than on the belief that they cannot be challenged.

The story’s most important move is symbolic: it reframes justice away from impulsive vengeance and toward exposure, disruption, and loss of legitimacy.

Rather than depicting bloodshed, the narrative centers on psychological unmasking. The “Black Mamba” becomes a metaphor for inevitability—the idea that terror systems collapse when they are forced into the light, when their participants begin to doubt one another, and when their supposed moral authority is revealed as hollow.

This reflects a real historical truth. White supremacist organizations in the early 20th century did not decline primarily because they were physically defeated by individuals. They weakened when federal scrutiny increased, when internal divisions surfaced, when economic and political incentives shifted, and when their secrecy was compromised.

The story’s emphasis on intelligence gathering, documentation, and network exposure mirrors how real progress occurred—through journalists, civil rights lawyers, federal investigators, and community organizers who chipped away at protected systems of abuse.

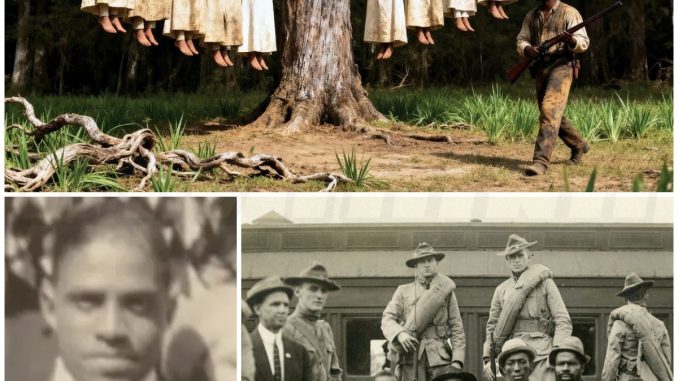

The ironwood tree, a recurring symbol in the narrative, illustrates this reframing powerfully. Historically, trees were used as instruments of terror. In the story, the tree is transformed—not through violent reversal, but through recontextualization. It becomes evidence, a marker of truth, and eventually a site of memory rather than fear.

This transformation reflects how societies process trauma. Places once associated with violence often become memorials, court exhibits, or educational sites. The act of naming what happened—and refusing to let it be erased—undermines the terror more effectively than replication ever could.

Another crucial element of the narrative is the rejection of lone-wolf heroism. While the protagonist begins isolated, the story ultimately emphasizes collective effort: allies with different skills, shared risk, and mutual accountability. This mirrors real civil rights movements, which succeeded not through individual acts of retaliation, but through sustained, organized resistance.

The so-called “Ironwood Circle” in the story is best understood as a metaphor for these alliances—networks built on trust, documentation, and protection of the vulnerable. The shift from personal loss to communal responsibility marks the protagonist’s true transformation.

Importantly, the narrative avoids portraying justice as emotional catharsis. The protagonist does not “win” by erasing enemies, but by removing their ability to operate, by forcing institutions to respond, and by creating conditions where harm becomes harder to hide.

This distinction matters, especially in modern retellings. Stories that glamorize violence risk reinforcing the very logic they claim to oppose. Stories that focus on exposure, accountability, and systemic disruption challenge power more effectively—and remain ethically defensible.

The final scenes of the narrative reinforce this message. The protagonist does not retreat into legend or anonymity. Instead, the struggle transitions from shadows into formal processes: investigations, resignations, testimonies. The emphasis is on the slow, imperfect movement of law toward justice, rather than instant resolution.

The return to the community is not a restoration of the past, but a redefinition of the present. Fear no longer operates invisibly. Silence is broken. Even those who once complied through inaction are forced to confront their choices.

The story’s endurance lies in this psychological truth: systems of terror survive on invisibility. Once seen clearly, they fracture.

Why, then, is this story often misrepresented with sensational headlines and violent imagery?

Because rage is easier to market than reflection.

But the deeper power of the “Black Mamba” narrative is not in imagined executions or dramatic reversals. It is in the quiet assertion that knowledge, discipline, and moral clarity can dismantle structures built on fear.

In that sense, the story is less about revenge than about agency reclaimed.

It speaks to generations who were told endurance was their only option, and it reimagines endurance as preparation—not for violence, but for confrontation with truth.

The legend persists not because it promises blood, but because it promises something harder: accountability.

And that is why it remains unsettling.

Not because it suggests that terror can be answered with terror—but because it insists that terror collapses when its myths are exposed, its networks documented, and its silence broken.

That is not a fantasy.

It is history’s most uncomfortable lesson.