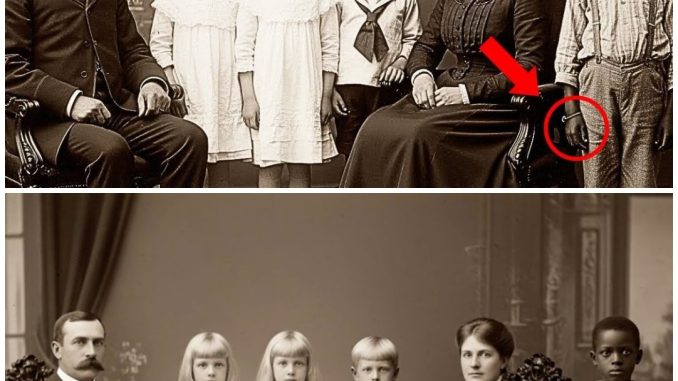

It was just a 1901 family portrait — but the child’s hand revealed something unsettling.

The attic of the old Baltimore townhouse hadn’t been opened in decades.

Dust drifted through a thin slice of afternoon light coming from a grimy window, revealing forgotten trunks, stacked boxes, and the angled ribs of wooden beams overhead.

Rebecca Miller had put off the work for months, but the estate sale was next week, and she could no longer avoid sorting through her late grandmother’s belongings.

She moved slowly through the clutter, creating neat piles.

Keep.

Donate.

Discard.

Most of it was exactly what she expected.

Outdated dresses sealed in brittle plastic.

Moth-bitten linens that smelled faintly of cedar.

Books with cracked spines and yellowed pages.

Then her fingers brushed something solid, wrapped in old newspaper.

She peeled back the layers carefully and found a heavy wooden frame.

The photograph inside made her stop.

It was a formal family portrait, the kind people commissioned at the turn of the century to project respectability.

A stern man sat in an ornate chair, his thick mustache trimmed sharply, his dark suit pressed as if he’d been prepared for inspection.

Beside him, a woman in a high-necked dress held herself rigidly, hair pulled back with a severity that made her expression feel even harder.

Between them stood three children: two blonde girls in matching white dresses, and a young boy in a sailor suit.

But it was the fourth child who caught Rebecca’s breath.

Off to the side, slightly separated from the others, stood a Black boy who looked about eight years old.

His clothing was simpler, his posture more guarded.

The white children faced the camera with a kind of certainty.

The boy’s eyes held something else.

Not drama.

Not performance.

Something quieter—like caution, or the practiced stillness of someone trying to take up as little space as possible.

Rebecca brought the frame closer to the window, squinting at the faded sepia tones.

That was when she saw it—the detail that stayed with her long after she put the photograph down.

The boy’s right hand was positioned oddly at his side.

And around his wrist, faint but unmistakable, was a ring-shaped mark.

Not a smudge.

Not a crease in the photograph.

A healed line that looked like an old injury—consistent with a restraint, or a repeated binding that had left its record on the skin.

Rebecca felt a chill move through her, not because she had any proof of what it meant, but because the image suggested a story that didn’t fit the clean, formal surface of the portrait.

Her grandmother had never mentioned this photograph.

In fact, she had never spoken much about the family’s history before 1920, always pushing questions away with vague answers and uncomfortable silence.

Rebecca turned the frame over, hoping to find names, a date, something ordinary.

On the back, in faded ink, were only four words:

The Thornon family, 1901.

She lifted her phone and photographed the front and back, her hands trembling slightly.

Something about the portrait felt wrong—not in a supernatural way, but in the way a small inconsistency can reveal a much larger truth.

The boy’s expression.

The mark on his wrist.

The way he stood apart from the others, like a figure added into the edge of the story.

As the afternoon light faded, Rebecca sat on an old trunk with the portrait resting across her knees.

She knew she should keep sorting.

But she couldn’t stop looking at that child’s face.

Who was he?

Why did he have that mark?

And why had her grandmother hidden this picture for so many years?

Rebecca barely slept that night.

The image kept returning behind her eyelids—the boy’s wrist, the small ring of healed skin, the careful distance between him and the other children.

By dawn, she’d made a decision.

She needed to know what the photograph meant, even if she didn’t like the answer.

She began the way anyone would in 2024.

Online databases.

Census records.

Genealogy forums.

Digitized newspapers.

She searched for the Thornon family in Baltimore around 1901.

The results were thin.

She found birth records for three children born to Harold and Constance Thornton between 1890 and 1895—Margaret, Elizabeth, and Charles.

No mention of a fourth child.

No record of a Black child connected to the household.

The absence felt loud.

On her lunch break from the hospital, Rebecca drove to the Maryland Historical Society.

The building sat on Monument Street, dignified and quiet, its halls lined with portraits of Baltimore families who had once shaped the city.

Rebecca requested access to city directories and newspaper archives from the turn of the century.

A librarian named Mrs. Patterson brought her several leatherbound volumes, handling them with the careful efficiency of someone who’d spent a lifetime among fragile paper.

“Thornton,” Mrs. Patterson repeated, glancing over her glasses. “That’s a name I haven’t heard in quite some time.”

Rebecca looked up. “You know the family?”

“Not personally,” Mrs. Patterson said. “But I’ve worked here for forty-three years. You develop a sense of which families prefer their histories… tidy.”

The sentence landed heavier than it should have.

Rebecca spent the next hours scanning directories and business notices.

Harold Thornton appeared as a textile merchant with an address on Mount Vernon Place, one of the city’s most prestigious areas at the time.

Advertisements for his business appeared regularly in the Baltimore Sun.

The tone was polished. Respectable. Confident.

But an obituary from 1923 made her pause.

Harold Thornton died at age 68, survived by his wife Constance and three children.

Three.

Not four.

Rebecca photographed the obituary and stared at her phone, her mind moving quickly.

Someone had erased the boy from the record.

The question was why—and what had happened to him.

As she left the historical society, the autumn wind cut through her jacket.

Baltimore, with its traffic lights and coffee shops, suddenly felt like a thin layer over another city—one lit by gas lamps, shaped by rigid hierarchies, and guarded by people who understood exactly which truths were allowed to exist.

She imagined 1901.

Horse-drawn carriages.

Formality as a shield.

And in a photographer’s studio, a Black child with a marked wrist standing near a white family, captured in a frame meant to outlast memory.

That evening, Rebecca called her mother in Florida.

“Mom,” she said carefully, “did Grandma ever mention the name Thornton?”

There was a pause.

“Why are you asking?”

“I found a photograph in the attic,” Rebecca said. “A family portrait from 1901.”

Another pause, longer.

“Rebecca… some things are better left alone.”

“Mom,” she said, keeping her voice steady, “there’s a child in the photo. A Black child. And his wrist… it looks like he was tied at some point. I need to know who he was.”

Her mother’s voice lowered. “Your grandmother made me promise I would never talk about it. She said it would only bring pain.”

“It’s already painful,” Rebecca said. “It’s painful not knowing.”

Three days later, Rebecca sat in her mother’s living room in Clearwater, having taken emergency leave from work.

The flight gave her time to prepare for a difficult conversation, but she still felt unprepared when her mother—Catherine—held the photograph like it weighed more than wood and paper.

Catherine looked older than Rebecca remembered.

She sat near the window, hands folded tightly in her lap, eyes fixed on the portrait.

Finally, she spoke.

“His name was Thomas,” she said softly. “At least that’s what they called him. We don’t know what his real name was.”

Rebecca leaned forward, every muscle tense. “Tell me.”

Catherine took a breath. “Your great-great-grandfather Harold Thornton wasn’t the man his obituary described. Even decades after slavery was abolished, some people refused to accept the change. They found ways to exploit vulnerable children and hide it behind respectable language.”

Rebecca’s stomach tightened. “What do you mean?”

“Black children who were orphaned,” Catherine said, voice shaking. “Or whose parents were gone. Some wealthy men would claim they were taking them in for ‘training’ or ‘work’—but it wasn’t care. It was control. Isolation. Unpaid labor. No schooling. No freedom to leave.”

Rebecca felt the room tilt slightly.

“And Thomas?” she asked.

Catherine’s eyes filled. “Thomas was brought into that house when he was six.”

She described a routine built around obedience and silence.

A child kept out of public view.

A child expected to work from morning until late at night.

A child not allowed to learn to read.

“And the marks on his wrist?” Rebecca asked, voice barely above a whisper.

“From rope,” Catherine said. “They would tie him when they left the house. They wanted to be sure he couldn’t run.”

Rebecca covered her mouth, fighting the urge to look away from the photograph.

“Then why is he in the family portrait?” she asked. “Why include him at all?”

Catherine wiped her eyes. “Because Constance—your great-great-grandmother—didn’t want him erased.”

She stood and retrieved a small wooden box from her bedroom.

Inside were letters with crumbling edges.

“They belonged to Constance,” Catherine said. “Your grandmother kept them hidden for decades.”

Rebecca unfolded the first letter carefully.

The handwriting was elegant but unsteady.

My dearest sister…

I can no longer bear the weight of this wrong.

Harold insists it is legal. He says we provide the boy food and shelter.

But I see the fear in Thomas’s eyes. I see the marks on his wrist.

And at night I hear him crying, while my own children sleep safely.

Rebecca blinked hard, her vision blurring.

“She knew,” Rebecca said.

“She knew,” Catherine repeated. “And she acted.”

The letters revealed Constance’s private struggle, written to her sister Harriet in Philadelphia.

In one, Constance admitted she had begun teaching Thomas to read in secret—bringing him into the library when Harold was away, hiding him when footsteps came unexpectedly.

In another, she described confronting her husband after hearing him discipline Thomas harshly for a small accident in the stable.

“I told him it was wrong,” Constance wrote. “That calling it ‘training’ does not make it different.”

Then Constance wrote a sentence that made Rebecca’s throat tighten:

I have decided he will be free, with or without Harold’s permission.

Catherine pulled out a brittle legal paper.

A notarized statement dated June 1901.

Constance had approached a lawyer named Joseph Brennan in secret, asking for legal help to remove Thomas from Harold’s control.

“But that would have caused a scandal,” Rebecca said, voice hoarse. “A woman opposing her husband publicly.”

“She understood that,” Catherine said. “She was willing to pay the cost.”

Then came the letter that explained the photograph.

Tomorrow we will have our family portrait taken.

Harold wants to present the image of a proper household.

He does not know I have arranged something with the photographer, Mr. William Ashford.

Thomas will be in the portrait.

If Harold tries to stop me from helping him, this image will be proof that Thomas existed in our home.

Proof that cannot be denied.

Rebecca sat back, stunned.

“She used the portrait as leverage,” she said.

Catherine shook her head gently. “She used it as protection.”

Rebecca read the next letter, dated the evening after the portrait was taken.

Constance described arriving early with Thomas, positioning him carefully at the edge of the frame.

She described Harold’s anger when he saw him there.

She described the photographer’s calm insistence that if Harold wanted the portrait, everyone would remain as arranged.

And she described Harold’s dilemma: leaving the studio would raise questions he didn’t want asked.

The portrait was taken.

Thomas flinched at the flash.

Constance steadied him with a hand on his shoulder.

“I can see that in the picture,” Rebecca murmured, looking again.

“You can,” Catherine said. “That moment matters.”

According to the letters, Constance then made plans to move Thomas out of Baltimore quietly.

She couldn’t use normal routes.

Harold had connections.

She needed help from people who knew how to move someone safely without attracting attention.

Through her lawyer, she was introduced to an older man named Elijah Warren, someone connected to networks that had once helped people reach safer places.

Even decades after the Civil War, the letters suggested, some people still relied on quiet routes—churches, trusted households, careful travel at night—for those who needed it.

Catherine nodded. “Your grandmother told me Elijah Warren was real. There’s a small plaque for him at a church in Baltimore. He helped establish schools after the war.”

The letters described the night Constance brought Thomas to a house near the harbor.

Thomas carried a small cloth bundle.

Constance gave him a wooden cross that had belonged to her grandmother.

“You are not property,” she wrote she told him. “You never were.”

Thomas asked a question that stayed with Rebecca long after she read it.

Why are you helping me?

Constance’s reply was simple.

Because it is right. Because I should have done it sooner.

The letter said Elijah and Thomas disappeared into the dark streets.

Constance returned home and waited.

Four days later, a telegram arrived:

Package delivered safely. All is well.

Rebecca let out a breath she didn’t realize she’d been holding.

But the story wasn’t over.

Harold discovered Thomas was gone and confronted Constance.

According to her writing, she placed the photograph on the table and told him plainly: if he tried to retrieve Thomas, she would take the story—and her evidence—to the authorities and the press.

Rebecca looked at her mother. “What happened to them?”

“The marriage never recovered,” Catherine said. “They stayed together for appearances. He kept his business. She devoted herself to charitable work. The children were told Thomas had been a temporary ward who returned to relatives.”

The photograph was hidden.

The letters were locked away.

The family chose silence.

“And Thomas?” Rebecca asked. “What happened to Thomas?”

Catherine’s expression changed—softening.

“That’s where the story becomes remarkable.”

She pulled out a worn leather journal.

“Your grandmother kept track of him,” she said. “Quietly. Through Harriet, and later through contacts in Philadelphia, Constance documented his life.”

Rebecca opened the journal carefully.

The entries ran from 1901 into the 1940s.

Thomas enrolled in school.

Thomas excelled in reading and math.

Thomas showed a talent for science.

Thomas graduated.

He attended Lincoln University.

He became a teacher.

He married.

He had children.

He became a principal.

The final entry, dated October 1945, stated Thomas passed away peacefully, surrounded by family, at 52.

In their last exchange, the journal said, he wrote that he had forgiven Harold, though he had not forgotten.

And he believed that educating children—teaching them to read and think—was the best answer to a past designed to limit him.

Rebecca closed the journal with shaking hands.

“Did he ever come back?” she asked.

“Once,” Catherine said. “In 1938, for Constance’s seventy-fifth birthday. He came quietly. They spoke privately for an afternoon. Your grandmother saw them. She was sixteen, and that’s when Constance told her everything—then made her promise to keep it quiet until everyone involved was gone.”

“Why keep it quiet?” Rebecca asked. “This is a story of courage.”

“It’s also a story of shame,” Catherine said gently. “A respected family that exploited a child long after the law changed. Constance wanted to protect her children and grandchildren from the stain. She believed silence was safer than truth.”

Rebecca looked again at the portrait.

Thomas’s position at the edge of the frame felt different now.

Not just separation.

A boundary.

A line between what the household wanted to show and what it tried to hide.

“She was wrong to hide it,” Rebecca said firmly. “This needs to be told.”

Rebecca returned to Baltimore with a mission.

She contacted the Baltimore Sun, the Maryland Historical Society, and several professors who specialized in post–Civil War African-American history.

She wanted to document Thomas’s story carefully, with context and evidence, not rumor.

Dr. James Carter, a historian at Johns Hopkins University, met her in his crowded office and listened without interruption as she laid out the photograph, the letters, and the journal.

When she finished, he sat back slowly.

“This is extraordinary,” he said. “We know exploitation of Black children continued in the decades after abolition, often disguised by acceptable terms. But documentation is rare. Families destroyed evidence. What you have—these materials—are invaluable.”

“Can you help me learn more about Thomas?” Rebecca asked.

Over the next two weeks, Dr. Carter searched archives and records.

He confirmed Thomas became an educator in Philadelphia under the name Thomas Freeman—a surname he chose, symbolizing the life he claimed for himself.

He taught in multiple schools.

He helped develop curriculum that included Black history and literature at a time when those subjects were often ignored.

And he influenced students who went on to become doctors, lawyers, teachers, and civil rights advocates.

A former student, Dorothy Hayes, wrote in a memoir that Mr. Freeman rarely spoke about his childhood, but he taught with a seriousness that made students feel education was not just instruction—it was dignity.

Rebecca traveled with Dr. Carter to Philadelphia.

They visited schools Thomas had worked in.

At the Morton School, where he served as principal, they met an elderly alumna named Gloria Richardson who remembered him clearly.

“Mr. Freeman knew every student by name,” Gloria said. “He asked about your family, your dreams. He made you feel like you mattered.”

“Did he ever talk about Baltimore?” Rebecca asked.

Gloria paused. “Once. I asked why he became a teacher. He said, ‘Someone helped me when I was eight, and I promised I would spend my life helping others.’ I didn’t understand then, but I never forgot the look in his eyes.”

They visited his grave at Eden Cemetery.

The headstone was simple:

Thomas Freeman, 1893–1945

Beloved teacher and father

Standing there, Rebecca felt the weight of everything she’d learned.

A boy treated as less than a person had turned his life into purpose.

He had created ripples that outlasted him.

“We have to tell people about him,” Rebecca said. “Not only what was done to him—but what he built.”

Dr. Carter nodded. “And we have to tell the full story, including the parts that make us uncomfortable. Constance’s courage matters. Harold’s wrongdoing matters. And it matters to acknowledge that there were likely other children like Thomas whose stories were never recorded.”

Rebecca understood.

This wasn’t a simple story of heroes and villains.

It was a story about the long afterlife of exploitation, the power of one person choosing to act, and the resilience of a child who grew into a leader.

Six months after finding the photograph, Rebecca stood in the Maryland Historical Society’s main gallery.

An exhibition had opened:

Thomas Freeman: From Bondage to Legacy

The centerpiece was the 1901 portrait, enlarged and lit to show what Rebecca first noticed in the attic—the child’s wrist, the quiet distance, the subtle hand on his shoulder.

Beside it was a timeline documenting Thomas’s life: from hidden childhood labor and isolation, to education, to teaching, to leadership.

The exhibition also offered broader context—how exploitative practices continued in the early twentieth century, how community networks sometimes helped children relocate safely, and how educators like Thomas fought for opportunity in an era shaped by segregation and discrimination.

Constance’s letters were displayed in climate-controlled cases.

The journal entries showed visitors that this was not only a story about harm.

It was a story about what can happen when someone refuses to let harm be the final chapter.

Rebecca had also located Thomas’s descendants.

His great-granddaughter, Angela Freeman, traveled from Atlanta for the opening.

She stood beside Rebecca, looking at the portrait of her great-grandfather as a frightened boy.

“We grew up hearing how much he valued education,” Angela said quietly. “My grandfather used to repeat his words: ‘They can take everything except what you know.’ I understand that differently now.”

A reporter from the Baltimore Sun approached.

“Miss Miller,” he asked, “some people wonder why you chose to share this now. Your family could have kept it private.”

Rebecca had expected that question.

She’d asked it of herself many times.

“Because silence doesn’t protect anyone,” she said finally. “My great-great-grandfather did something wrong. My great-great-grandmother tried to correct it. And Thomas built a meaningful life from a childhood designed to limit him. All of those truths matter.”

Angela nodded. “His life teaches us resilience. But it also teaches responsibility. Constance acted. The question is—would we?”

The exhibition ran for three months and drew thousands of visitors.

Schools brought classes.

Local coverage sparked conversations about Baltimore’s history and the long shadow cast by racial injustice.

The photograph that had been hidden for more than a century became a catalyst for public discussion.

But for Rebecca, the most meaningful moment came on a quiet Tuesday afternoon three weeks after the opening.

She was checking details in the gallery when a young Black girl—maybe nine or ten—walked up.

“Are you the lady who found the picture?” the girl asked.

“Yes,” Rebecca said.

“My teacher told us about Thomas Freeman,” the girl continued. “She said he was treated like he didn’t matter, but he became a principal. Is that true?”

“It’s true,” Rebecca said.

The girl studied the portrait closely.

“His wrist looks like it has a mark,” she said.

“It does,” Rebecca replied, keeping her voice careful and gentle. “It’s a mark from being tied up when he was very young.”

The girl was quiet for a moment.

“Did it hurt?” she asked.

Rebecca knelt so they were at eye level.

“Yes,” she said softly. “I think it hurt a lot. But he didn’t let that be the end of his story. He became someone who helped other children.”

The girl nodded slowly.

“My mom says we have to remember history so we can make the future better,” she said.

“Your mom is right,” Rebecca answered. “That’s why this matters.”

When the girl walked away, Rebecca felt something shift inside her.

This wasn’t only about documenting the past.

It was about giving people—especially young people—examples of courage, accountability, and possibility.

That night, the light faded in Rebecca’s Baltimore apartment as she sat at her desk surrounded by papers, photographs, and notes.

Eight months had passed since she found the portrait, and her life had changed in ways she never expected.

She had taken leave from the hospital to work on a book about Thomas Freeman and the hidden history of post-abolition exploitation.

Dr. Carter agreed to co-author it.

Several publishers had expressed interest.

Rebecca also helped establish a scholarship fund in Thomas’s name for students pursuing careers in education, a way to extend his legacy forward.

But tonight she was focused on something deeply personal.

She had finally received copies of Thomas’s papers from Lincoln University’s archives.

Reading his words felt like hearing his voice directly.

One essay from 1915 made her stop.

On the nature of freedom.

Many believe freedom is simply the absence of restraints.

I know differently.

I wore restraints once, though they were called by softer names.

When those restraints were removed, I learned true freedom is the ability to determine one’s own path.

Freedom is the right to education, to self-improvement, to knowledge without restriction.

It is the opportunity to lift others as one climbs.

It is the choice to build rather than destroy, to teach rather than harden, to forgive without forgetting.

I was eight years old when a woman who could have remained silent chose instead to see me as a child worthy of dignity.

That act changed my life.

It taught me that freedom is not only claimed, but sometimes protected by courage.

We are bound together, and none of us is truly free until all of us are.

Rebecca read the passage three times, tears slipping down her face.

This was Thomas—thoughtful, clear, refusing to let bitterness define his work.

She picked up the photograph again, the one that started everything.

Over time, she had learned to see past the initial shock and recognize what it truly represented.

Evidence of a turning point.

A moment when one person chose courage over silence.

Her phone buzzed.

A message from Angela Freeman.

It included a photo: Angela’s daughter had just been accepted to medical school.

The caption read: He would have been so proud.

Rebecca smiled through tears.

This was the legacy.

Not the hardship of his earliest years, but the lives he touched and the generations shaped by his belief in education.

Every student he taught.

Every descendant who pursued learning.

All of it flowed from that choice in 1901 when Constance Thornton decided a child’s dignity mattered more than social standing.

Rebecca looked at her computer screen, where the first chapter of her book was open.

She reread the opening lines.

This is a story about a photograph taken in Baltimore in 1901.

It is also a story about silence and truth, wrongdoing and courage, and a boy named Thomas who was treated as if he didn’t matter—but chose to build a life that proved otherwise.

She saved the document and walked to the window.

Baltimore spread out below.

The harbor where Elijah Warren had once guided Thomas toward safety.

The neighborhoods where the Thornon family lived.

The streets that connected past to present.

She thought about all the photographs sitting in attics across the country.

How many contained stories someone tried to bury.

How many children like Thomas were never documented.

And how many people—like Constance, like Elijah—chose to act anyway.

The portrait of Thomas Freeman would remain in the Maryland Historical Society’s permanent collection.

Students would see it and ask questions.

Historians would study it and add context.

And perhaps other families would look more closely at their own histories, choosing honesty over silence.

Rebecca returned to her desk.

She had work to do.

A book to finish.

A scholarship fund to grow.

A legacy to honor.

But for now, she simply sat with the photograph, Thomas’s eight-year-old eyes meeting hers across more than a century.

“Thank you,” she whispered.

For surviving.

For becoming more than what others tried to make you.

For reminding us that the past doesn’t have to define the future.

Outside, the sun sank over Baltimore, coloring the sky amber and gold.

A city that once held both injustice and courage continued to carry both truths.

And a boy once treated as property had become a teacher whose impact echoed across generations.

The photograph remained where Rebecca had placed it.