On September 14, 1847, the rice-growing low country south of Charleston, South Carolina, awoke to a scene that would be quietly erased from public memory.

Inside Grantham Plantation, one of the region’s most established estates, members of the Grantham household were discovered unresponsive in their rooms. Seven lives were lost in a single night. There were no signs of forced entry, no sounds reported by neighbors, and no witnesses who claimed to have seen anyone enter or leave.

By morning, one name dominated every whispered conversation: Samuel.

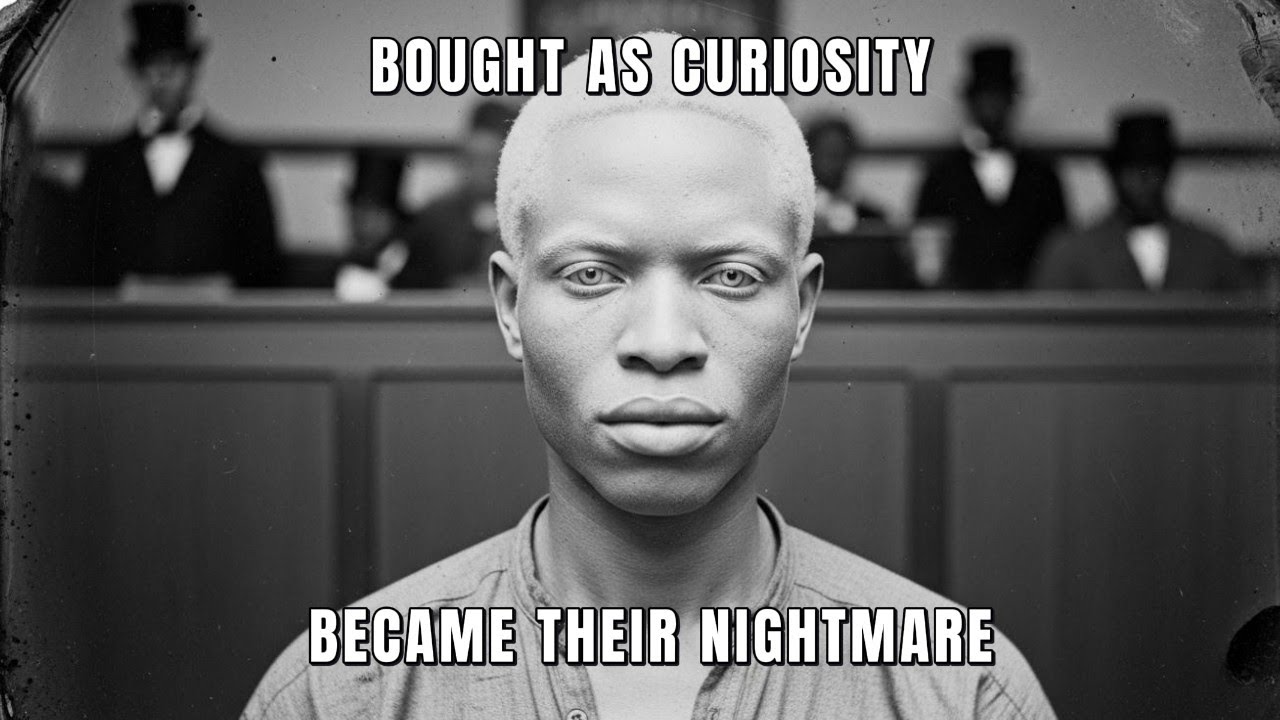

Samuel was a 22-year-old enslaved man who had vanished sometime before dawn. His disappearance immediately drew attention because he was not like anyone else on the plantation—or in the region. Purchased three years earlier for an unusually high price, Samuel was known for his extremely light skin and pale eyes, a rare genetic condition that made him the subject of constant attention.

Charleston’s newspapers printed a brief notice. Then, just as quickly, the coverage stopped.

No arrest was made. No public trial followed. No burial records were released. The case was officially closed with a single line: The suspect is believed to have drowned while attempting to flee.

Privately, few believed it.

Among the enslaved communities of the Lowcountry, a different version of events began to circulate—one that spoke not of panic or rage, but of planning, patience, and an intelligence that had been underestimated for far too long.

The Collector of Curiosities

In 1844, Thaddeus Grantham traveled to Charleston’s slave market not to purchase labor, but to acquire something unusual.

Grantham was a gentleman planter with a reputation for refinement and eccentric interests. His home contained cabinets of rare insects, mineral samples, and volumes devoted to what was then called “racial science.” He enjoyed presenting himself as a man of reason and curiosity.

That spring, a broker guided him toward a holding area and introduced him to a young man whose appearance immediately set him apart. Samuel’s skin was almost porcelain in tone. His hair was nearly white. His eyes, light and translucent, unsettled anyone who held their gaze for too long.

The broker described Samuel as educated and literate, but “unsuitable for field labor.” Grantham was intrigued.

He asked Samuel what he had last read.

“The Gospel of Luke,” Samuel replied calmly.

Grantham asked him to recite a passage. Samuel did so without hesitation.

In that moment, Grantham believed he had found something rare: not just an enslaved person, but a subject. A living anomaly he could observe, document, and discuss among his peers.

He purchased Samuel on the spot.

Life as an Object of Study

At Grantham Plantation, Samuel was assigned a small room near the main house. He did not work in the fields. Instead, his days were spent assisting indoors, always under observation.

Grantham recorded notes about Samuel’s appearance, his reaction to sunlight, his behavior, and his intellect. Visitors were invited to see him. Conversations took place as though Samuel were furniture rather than a person.

At social gatherings, Grantham often called Samuel into the room to pour drinks or stand nearby while guests debated theories about race and biology. Samuel listened silently, memorizing voices, faces, and habits.

Only one member of the household treated him differently: Grantham’s youngest daughter, Catherine. She spoke to him as a person, brought him books, and asked him questions. Through these interactions, Samuel learned the layout of the house, the routines of the staff, and the location of documents Grantham considered private.

While Grantham believed he was studying Samuel, the reverse was also true.

The Patient Observer

For three years, Samuel endured a life designed to strip him of dignity. He responded not with visible resistance, but with attention.

He practiced copying handwriting until he could reproduce Grantham’s script perfectly. He learned how documents were dated, signed, and stored. He observed which doors were locked and which were not. Which servants moved at night. Which habits never changed.

To the Grantham family, Samuel appeared compliant and quiet—another curiosity absorbed into the daily rhythm of the estate.

To those who watched more closely, he appeared deliberate.

When an elder once asked him whether he intended to act on the treatment he received, Samuel reportedly answered with a question of his own:

“If someone studies you as less than human, what do you owe them?”

The Decision That Changed Everything

In early 1847, Grantham announced plans to bring Samuel to Charleston to be presented before a medical society as an example of “racial anomaly.” The event was framed as academic. Samuel understood it differently.

That announcement marked the moment when observation turned into resolve.

What happened later that year unfolded quietly and with unsettling precision.

On a night when the household slept, the Grantham estate fell silent in a way it never had before. By morning, members of the family were found unresponsive in separate rooms. There were no signs of chaos, no evidence of struggle that authorities could easily describe.

Samuel was gone.

Household animals had been secured earlier that evening, preventing disturbance. Documents were missing from Grantham’s study. Cash reserves had been selectively removed.

It was not disorder.

It was execution of a plan.

The Panic No One Admitted

Search parties followed tracks toward the nearby river and lost them there. Authorities quickly settled on drowning as the official explanation. It was neat. It avoided uncomfortable questions.

But among plantation owners across the Lowcountry, fear spread.

If one enslaved man—treated as an object, studied, and dismissed—could orchestrate such an outcome and vanish without trace, then the entire system felt suddenly exposed.

Behind closed doors, prominent planters agreed on one thing: if Samuel were ever found, there would be no public process.

No one wanted scrutiny.

A Ghost on the Move

Over the following months, reports surfaced of unexplained disappearances of money and documents from plantation offices across South Carolina and Georgia. Always small amounts. Always specific papers.

Sometimes a note was left behind, written in elegant English.

One message, copied by hand and passed quietly between enslaved communities, read:

“You believed you understood me because you measured me. But measurement is not understanding. Every house built on certainty forgets how fragile certainty is.”

The notes terrified those who recognized their meaning.

Samuel was no longer seen as a man. He became an idea.

The Photograph

In July 1847, a traveling photographer in Columbia claimed to have taken a portrait of a pale man wearing tinted spectacles. The man reportedly asked that the image capture his features clearly, without disguise.

“So there is a record,” he said, “of who I was before they decided what I should be.”

The daguerreotype showed a composed profile—neither angry nor fearful.

After that, sightings became rare.

The Last Trace

The final credible account came from abolitionist networks near the Canadian border. A man matching Samuel’s description was assisted north and crossed into Ontario before winter.

According to one recollection, he carried a single page from a plantation ledger. Once across the border, he destroyed it and said only, “Now it’s finished.”

No confirmed record of Samuel exists after that moment.

The Story That Would Not Stay Buried

By 1849, Charleston authorities officially closed the Grantham case. Newspapers printed a fabricated conclusion describing the suspect’s remains as “recovered.” The city moved on.

But among Black communities throughout the South, the story endured.

Samuel became a symbol—not of violence, but of what happens when intelligence is dismissed, when curiosity replaces humanity, and when observation flows only one way.

Years later, a formerly enslaved woman reportedly said:

“They called him dangerous. But danger was built into the system long before he acted. He just revealed it.”

The Meaning That Remains

Grantham Plantation no longer exists. The land has changed hands many times. Homes now stand where fields once stretched.

Yet the story persists because it touches something deeper than crime.

It asks what happens when people are treated as specimens instead of souls. When curiosity becomes control. When patience becomes strategy.

Samuel was bought as a curiosity.

History remembers him as a reckoning.

Not because of what he did—but because of what the system made inevitable.