The General German Commanders Could Not Predict: Why Patton Inspired Unusual Fear

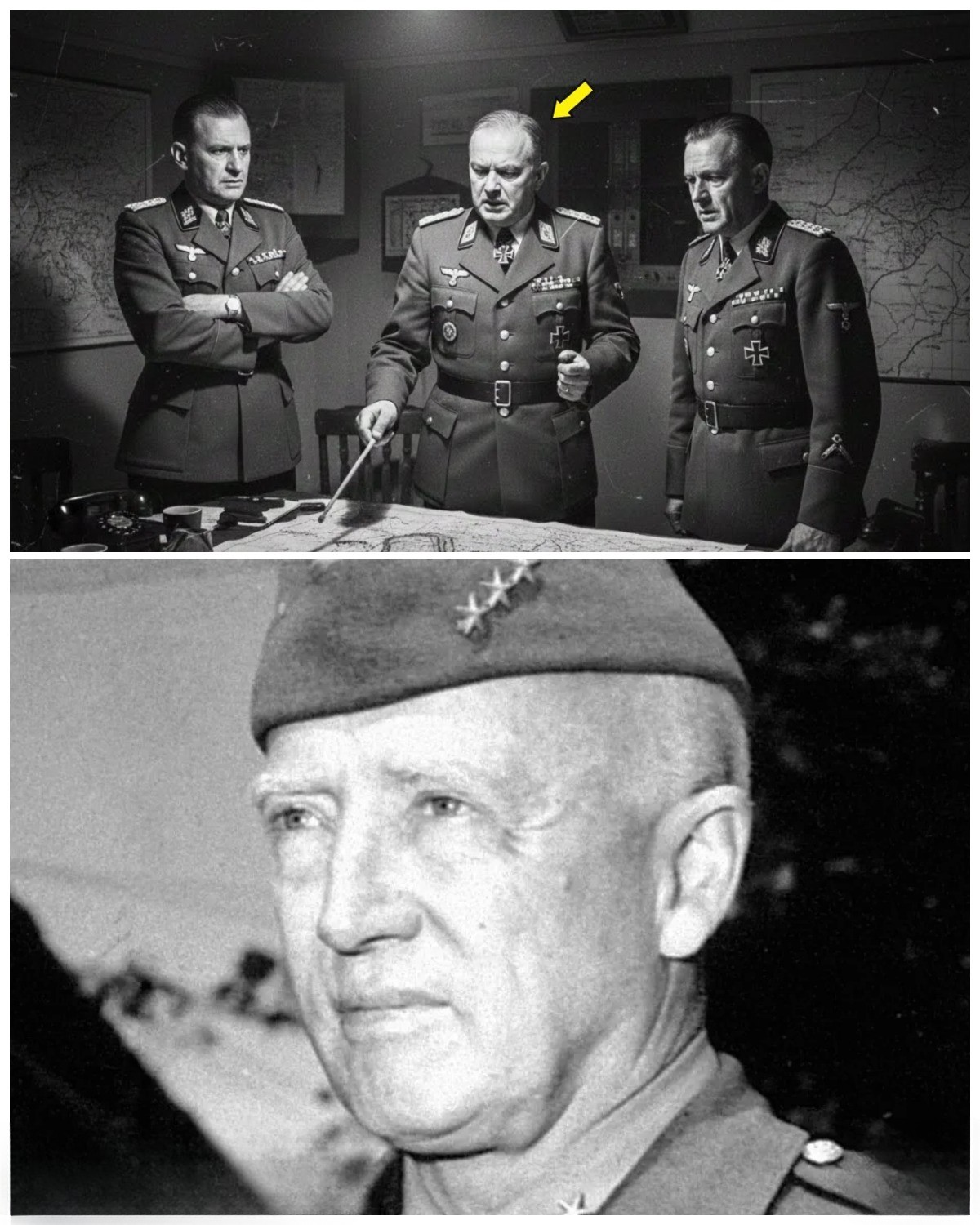

Among Allied commanders of the Second World War, few names provoked as much unease within the German high command as George S. Patton. This was not because he was the most senior, nor because his forces were always the largest. It was because he operated at a tempo German planners understood deeply—and could not reliably counter.

German war doctrine prized speed, shock, and decisive maneuver. Blitzkrieg was not merely a tactic but a worldview: war was won by disrupting the enemy’s ability to think coherently, by collapsing decision-making faster than orders could travel. What unsettled German commanders about Patton was not that he fought differently from them, but that he thought the same way—and sometimes faster.

Early Attention from Berlin

German intelligence first took sustained notice of Patton during Operation Torch in November 1942. Prior assessments of American forces had assumed a cautious, industrial style of warfare: deliberate advances, heavy reliance on logistics, and limited operational audacity.

What unfolded in North Africa challenged those assumptions. Patton’s Western Task Force moved with unexpected speed and decisiveness. Casablanca fell quickly. Coordination with Vichy French forces was handled with political calculation rather than brute force. To German analysts, the campaign suggested an American commander operating with an instinctive grasp of tempo.

More troubling was what intelligence officers learned about Patton himself. He had studied German military theory extensively, reading manuals and operational histories in the original language. He had walked European battlefields, not as a tourist but as a student of maneuver. He understood the logic behind German decisions—not merely their outcomes.

This mattered. An enemy who understands your doctrine from the inside is not constrained by it. He can exploit it.

Kasserine and the Misreading of Failure

The defeat of American forces at Kasserine Pass in February 1943 initially seemed to confirm German expectations. Poor coordination, inexperience, and confused command structures resulted in a clear setback. German reports from the period reflect a brief confidence that American forces had reached their natural limit.

What German planners underestimated was the American response.

Rather than withdrawing Patton from the theater or diluting his authority, Allied command placed him directly in charge of the battered II Corps. This decision was not a retreat from risk but an embrace of it.

Patton imposed discipline with relentless intensity. Training was accelerated. Inspections were constant. Standards were uncompromising. Within weeks, the same units that had broken at Kasserine were maneuvering aggressively, probing German positions rather than reacting to them.

German after-action reports from this period begin to note a shift in American behavior. The U.S. Army was no longer merely adapting; it was learning rapidly—and Patton appeared to be the catalyst.

Sicily: Tempo as a Weapon

The Sicilian campaign in 1943 reinforced these concerns. Officially, Patton’s Seventh Army was assigned a supporting role, protecting the flank of Montgomery’s British Eighth Army. In practice, Patton treated the assignment as a constraint to be overcome.

Advancing across difficult terrain, Seventh Army moved with a speed that surprised both allies and enemies. Towns fell in rapid succession. Messina was reached before Montgomery’s forces, despite Patton’s longer route and fewer resources.

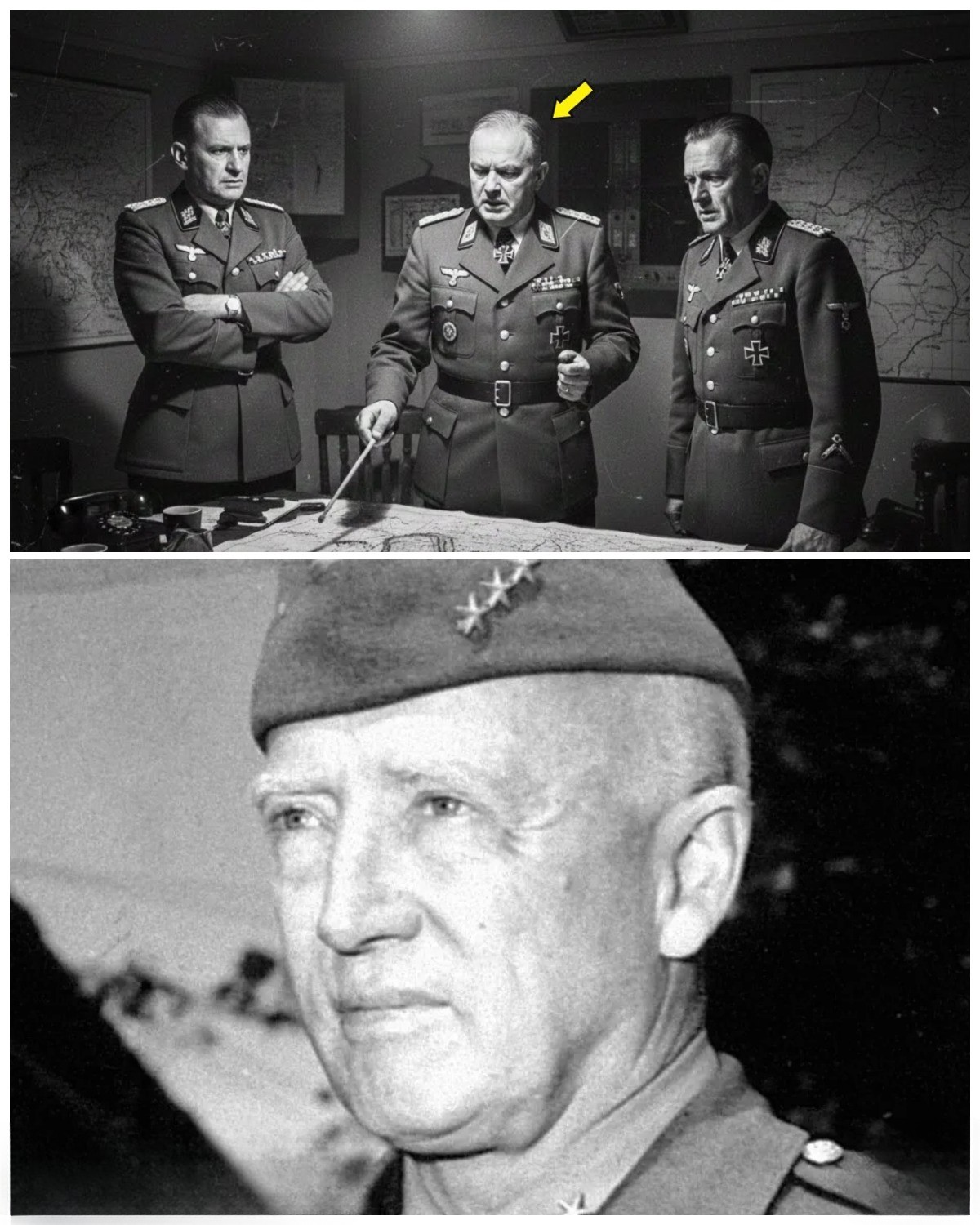

German reports did not attribute this to American doctrine. They described it as familiar—uncomfortably familiar. The language used in postwar interviews would later describe Patton’s methods as “German tactics executed without German hesitation.”

Patton accepted risks that Allied doctrine often discouraged. He attacked with incomplete information, trusted momentum over consolidation, and assumed that confusion favored the attacker. These were principles German commanders recognized immediately—because they had built their own early-war successes on them.

Politics, Scandal, and Strategic Preservation

Patton’s career nearly ended in Sicily following incidents in military hospitals, where he struck soldiers suffering from combat fatigue. In Washington, the actions were widely condemned. Eisenhower reprimanded Patton publicly and removed him from frontline command.

German intelligence monitored the episode closely. From Berlin’s perspective, Patton appeared politically radioactive. If removed permanently, he would cease to be a factor.

But the Allies made a subtler calculation. Patton was sidelined publicly but preserved strategically. He disappeared from the battlefield, not from planning.

To German commanders, this ambiguity was unsettling. A dangerous opponent had not been destroyed—only hidden.

The Phantom Army Before Normandy

In the months leading up to D-Day, German intelligence tracked Patton’s movements obsessively. His visibility in England, combined with his reputation for aggressive command, made him a natural focal point for Allied deception.

The fictional First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG), complete with inflatable tanks, false radio traffic, and fabricated airfields, exploited German expectations. Patton was placed at its head.

The deception worked not because it was elaborate, but because it was plausible. German commanders believed Patton would lead the main invasion force—and therefore assumed it would strike at Pas de Calais.

As a result, armored reserves remained pinned far from Normandy for weeks after the landings. The fear was not abstract. It was Patton-specific. German commanders hesitated to redeploy forces because they believed Patton had not yet revealed his hand.

In war, hesitation is often more costly than error.

The Release of the Third Army

When Patton finally took command of the Third Army in August 1944, the results validated German anxieties. Breaking out of Normandy, Third Army advanced at a pace that rendered existing operational maps obsolete.

Patton did not pursue in straight lines. He pivoted, wheeled, and exploited gaps faster than German command structures could respond. Supply lines stretched not because of mismanagement, but because the front moved faster than logistics doctrine anticipated.

The encirclement at Falaise was not merely a tactical success. It demonstrated Patton’s defining advantage: the ability to alter the geometry of a campaign faster than the enemy could process it.

German commanders later described issuing orders only to discover the situation had already changed. The battlefield moved faster than paperwork.

Doctrine Turned Against Its Creators

In postwar interviews, German officers frequently contrasted Allied commanders. Montgomery was methodical and predictable. Bradley was cautious and deliberate. Both could be countered with planning.

Patton was different. He disrupted rhythm.

He applied blitzkrieg principles not as historical imitation but as living practice, backed by American industrial capacity. The combination was devastating. German doctrine, designed for limited resources, now faced an adversary who could execute the same ideas with overwhelming material support.

This inversion created a psychological shock. The Germans were no longer the fastest thinkers in the room.

The Ardennes and the Final Proof

The Battle of the Bulge provided the final confirmation. When German forces launched their winter offensive, Allied commanders required time to assess, reposition, and reinforce.

Patton had already prepared contingency plans.

Within days, Third Army executed a ninety-degree pivot, advancing north to relieve Bastogne. German timelines had been calculated in weeks. Patton’s were measured in days.

German commanders later acknowledged that this discrepancy destroyed their remaining confidence. They could plan operations. They could predict responses. They could not predict Patton.

Why Fear Persisted

The fear Patton inspired was not personal. It was structural.

German commanders faced an opponent who understood their instincts, shared their reverence for speed and shock, and was willing to push those principles further than doctrine allowed. He did so without the constraints of scarcity.

Patton did not merely counter German strategy. He reflected it back, amplified.

In that mirror, German officers saw their own strengths transformed into vulnerabilities. That recognition—more than any single battle—is why Patton’s name appeared again and again in German intelligence assessments.

He was not simply an enemy.

He was proof that their way of war could be used against them—and improved.

Nếu bạn muốn, mình có thể:

- Rút xuống ~1200 từ cho Facebook tối ưu CTR

- Chỉnh lại giọng văn học thuật hơn để đăng blog / medium

- Viết thêm phiên bản “Why Patton Still Matters in Modern Warfare” để nối sang phân tích quân sự hiện đại

Bạn muốn đi tiếp hướng nào?