When Whiskey Ruled the Workday: America’s “Grog Time” Tradition of the 1830s

In 1830s America, it was not unusual for a factory bell to ring in the middle of the day — not to mark lunch, but to signal what workers cheerfully called “grog time.” This was the moment when laborers paused their work to take a small ration of whiskey, a tradition that seems almost unbelievable today.

At that time, the average American adult was consuming what historians estimate to be the equivalent of 1.7 bottles of whiskey per week, a staggering amount compared to modern standards. Far from being taboo, alcohol — especially whiskey — was woven into the fabric of daily life.

How did this practice come to be, and what caused it to disappear? The story of “grog time” is a fascinating glimpse into how cultural attitudes toward alcohol, labor, and productivity have evolved over the centuries.

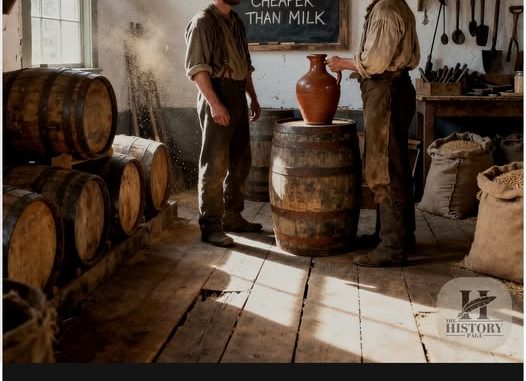

In the early 19th century, whiskey was more than a drink — it was part of the national identity. Water sources were often unsafe, milk spoiled easily, and tea or coffee could be expensive in some regions. Whiskey, by contrast, was cheap, portable, and long-lasting.

Historians from the Smithsonian Institution and the Library of Congress note that after the American Revolution, domestic distilling became widespread. Farmers, especially in frontier regions like Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee, often turned surplus grain into whiskey, which could be traded or consumed.

By the 1830s, America was producing millions of gallons of whiskey each year. It was served at social events, political gatherings, and — remarkably — in workplaces.

What Was “Grog Time”?

The term “grog” originated in the British Navy, referring to a diluted rum ration given to sailors. American workers adapted the word for their own daily whiskey ritual.

In many factories, mills, and construction sites, employers would actually schedule a “grog bell” — a moment each day when workers could stop and take a drink. In some cases, it was provided by the company itself as part of workplace culture or even as a form of incentive.

Newspapers and diaries from the period describe how workers lined up with tin cups or small bottles, sharing a communal toast before returning to work. The idea was that whiskey lifted morale, provided warmth in winter, and helped relieve fatigue from long hours of manual labor.

While modern readers might see this as dangerous or unprofessional, 19th-century Americans viewed alcohol very differently. Sobriety was not a social norm; moderation, not abstinence, was considered the virtue.

How Much Did People Really Drink?

According to data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and historical research by the American Historical Association, per-capita alcohol consumption in the early 1800s was about 7 gallons of pure alcohol per year — roughly triple today’s average in the United States.

Whiskey was the drink of choice because it was cheap and widely available. Taxes were low, production was local, and social customs supported its use. It was common to drink whiskey at breakfast, with lunch, and again in the evening.

Children and women also occasionally consumed diluted forms such as cider or beer, though whiskey was primarily a working man’s drink.

The Turning Point: The Temperance Movement

By the late 1830s and 1840s, attitudes began to shift. Religious leaders, social reformers, and public health advocates warned that the country’s high alcohol consumption was leading to poverty, family breakdown, and workplace accidents.

This moral and social campaign — known as the Temperance Movement — gained national momentum. Organizations such as the American Temperance Society, founded in 1826, promoted total abstinence and argued that alcohol was destroying communities.

Gradually, “grog time” disappeared from workplaces. Employers began banning alcohol on the job, and water or coffee replaced whiskey as the standard break beverage.

By the 1850s, many factories had officially ended the practice, aligning with broader efforts to promote industrial discipline, punctuality, and productivity.

From Whiskey Bells to Coffee Breaks

The decline of “grog time” marked a larger transformation in American work culture. As the Industrial Revolution matured, efficiency and sobriety became essential traits of the modern worker.

The rise of the railroad industry, manufacturing plants, and urban offices demanded alertness and precision. Accidents caused by alcohol use were increasingly viewed as preventable tragedies rather than inevitable mishaps.

Interestingly, the concept of a scheduled break didn’t disappear — it simply evolved. By the early 20th century, coffee had replaced whiskey as the beverage of choice for workers. The first “coffee breaks” appeared in factory towns in the 1900s and became widespread by the 1950s, symbolizing productivity and alertness rather than indulgence.

Lessons from History

Looking back, the “grog time” tradition illustrates how cultural norms and workplace expectations are shaped by their era. In the 1830s, whiskey represented community and endurance; today, it would be viewed as a serious workplace hazard.

Historians emphasize that it’s important to understand these customs in context. People of that era did not have modern medical knowledge about alcohol’s long-term effects, and social drinking was embedded in daily life from farm to factory.

At the same time, the eventual shift toward sobriety and health awareness reflects the country’s growing emphasis on safety, professionalism, and public health — values that continue to define workplace culture today.

The Legacy of “Grog Time” in Modern America

Though the whiskey bell has long been silenced, the story of “grog time” still resonates in discussions about labor rights, workplace culture, and even how societies define “break time.”

Today’s employees enjoy regulated rest periods, ergonomic standards, and wellness initiatives that trace their roots back to the 19th century’s evolving labor movements. In a sense, every coffee break or team lunch is a distant echo of those early moments when workers paused together to share something that lifted their spirits — though thankfully now it’s caffeine, not whiskey, keeping the workforce energized.

Conclusion

The tale of America’s 1830s “grog time” is both strange and revealing — a reminder that what seems normal in one century may seem unimaginable in another.

From whiskey rations to water coolers, the story of workplace breaks tells us how much the world has changed — and how the rhythms of work, rest, and community continue to define human experience.

As historians continue to explore this fascinating period, “grog time” remains a curious but telling symbol of early America’s relationship with work, culture, and change.