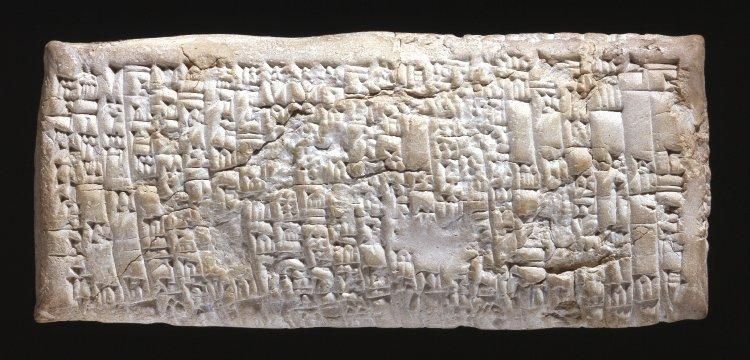

For more than a century, a small clay tablet known as Plimpton 322 has challenged historians’ understanding of ancient mathematics. Preserved today at Columbia University, the tablet dates back nearly 3,700 years to the Old Babylonian period and continues to reshape how scholars view early scientific knowledge.

At first glance, Plimpton 322 appears modest: a baked clay tablet roughly five inches wide, inscribed with columns of numbers written in cuneiform. When it was discovered in the early 20th century near the ancient city of Larsa (in present-day Iraq), many researchers initially assumed it was a teaching aid or an accounting document.

That interpretation, however, proved incomplete.

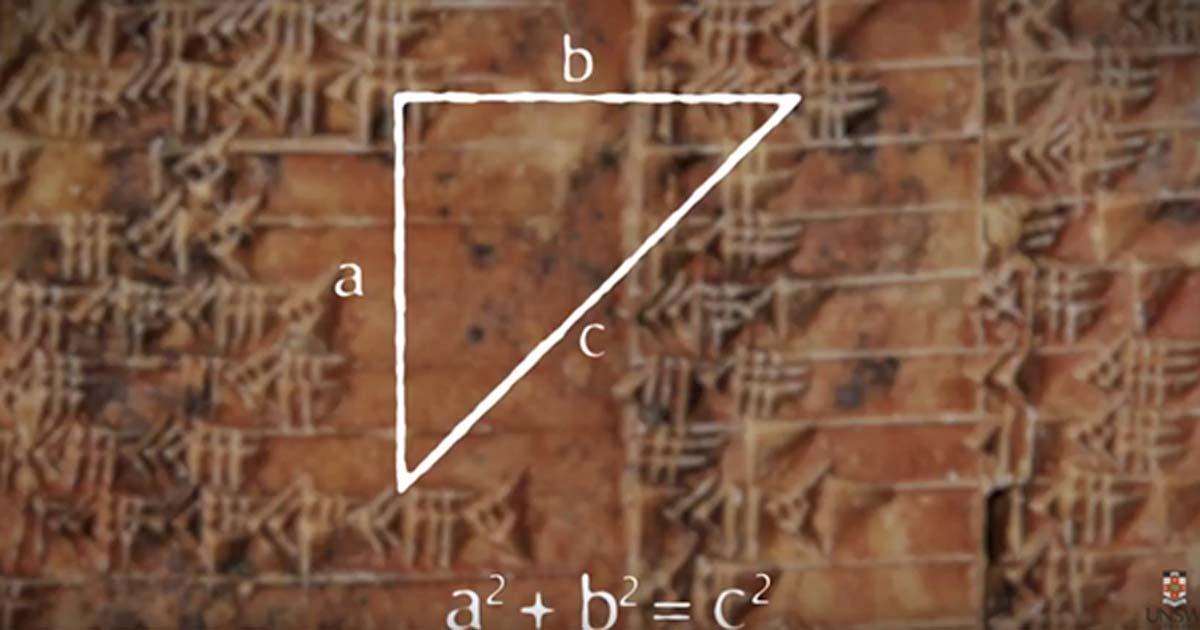

What set Plimpton 322 apart was the numerical structure recorded on its surface. The numbers follow precise relationships that correspond to right-angled triangles, relationships now commonly associated with what later became known as the Pythagorean theorem.

The striking detail is chronological. The tablet predates the Greek mathematician Pythagoras by more than a millennium. This raised a fundamental question: were Babylonian scholars already working with advanced geometric principles long before classical Greek mathematics?

Over decades, mathematicians and historians debated whether the tablet represented a list of exercises, a numerical curiosity, or something more systematic.

A New Look Through Computational Analysis

In recent years, researchers have revisited Plimpton 322 using modern computational methods. High-resolution imaging and algorithmic analysis allowed scholars to examine numerical patterns with greater precision than was previously possible.

Rather than relying on assumptions shaped by Greek mathematical traditions, these analyses focused strictly on what the numbers themselves reveal. The result was a clearer understanding of the tablet’s structure and intent.

The evidence suggests that Plimpton 322 is not a random collection of examples. Instead, it functions as a structured table describing a sequence of right triangles, organized according to consistent numerical ratios.

A Different Approach to Trigonometry

Unlike modern trigonometry, which relies on angles and approximations, Babylonian mathematics used exact ratios expressed in a base-60 (sexagesimal) number system. This system allowed for remarkable numerical precision, avoiding the rounding errors that appear in many decimal-based calculations.

Plimpton 322 appears to record these ratios systematically, providing values that would allow a trained scribe or builder to calculate slopes and proportions with exactness. In effect, it represents an early form of trigonometric thinking—one that is ratio-based rather than angle-based.

This does not mean Babylonian scholars conceptualized mathematics in the same way modern students do. However, it does demonstrate that they possessed practical and theoretical tools capable of solving complex geometric problems.

Practical Uses in the Ancient World

Babylonian mathematics was deeply connected to real-world applications. Surveying land, constructing temples, and designing large-scale architecture required reliable methods for measuring distance and proportion.

A tablet like Plimpton 322 would have been valuable for training scribes or specialists tasked with these responsibilities. By listing precise numerical relationships, it offered a repeatable reference system rather than a collection of trial-and-error solutions.

This perspective aligns with what is known about Mesopotamian education, which emphasized procedural knowledge, accuracy, and professional competence.

Rethinking the History of Mathematics

The significance of Plimpton 322 lies not in overturning history, but in refining it. For generations, educational narratives have emphasized ancient Greece as the birthplace of advanced mathematics. While Greek scholars undoubtedly played a crucial role in formalizing mathematical theory, tablets like Plimpton 322 show that sophisticated mathematical reasoning existed much earlier in other cultures.

Rather than a single linear progression, the history of mathematics appears increasingly as a mosaic of parallel developments across civilizations, each shaped by local needs, tools, and intellectual traditions.

What Plimpton 322 Does—and Does Not—Prove

It is important to be precise about what the tablet demonstrates. Plimpton 322 does not show that Babylonians developed modern trigonometry as it is taught today. It does not imply the existence of lost super-technologies or hidden scientific revolutions.

What it does show is that Babylonian scholars understood numerical relationships with a level of rigor and organization that rivals later mathematical systems in specific contexts.

This insight enhances respect for ancient knowledge without resorting to speculation unsupported by evidence.

Why the Tablet Still Matters Today

Plimpton 322 remains relevant because it highlights how knowledge can be overlooked when interpreted through a narrow historical lens. For decades, the tablet sat quietly in an archive, its significance underestimated simply because it did not fit familiar narratives.

Modern analytical tools have not changed the tablet itself; they have changed our ability to read it accurately.

This serves as a reminder that many ancient artifacts may still hold insights waiting to be fully understood—not because they are mysterious, but because careful scholarship takes time.

A Broader View of Human Knowledge

The story of Plimpton 322 reinforces a broader truth about human history: intelligence and innovation are not confined to any single culture or era. Ancient societies developed sophisticated systems tailored to their environments and needs, often achieving results that continue to impress modern researchers.

By studying these achievements with humility and methodological rigor, historians can build a more inclusive and accurate picture of humanity’s intellectual past.

Plimpton 322 does not force us to question history itself—but it does encourage us to question oversimplified versions of it. And in doing so, it deepens our appreciation for the many paths through which human knowledge has grown.