Saturday, October 4, 1952, Harlem carried the kind of calm that never truly meant peace.

The air was cool for early October, the sky clear enough for the moon to look close, almost watchful. On the streets below, people moved between corner stores, barbershops, and late-night diners with the familiar rhythm of a neighborhood that had learned how to live with tension. Harlem in that era didn’t just have nightlife. It had invisible boundaries. It had names people said carefully. It had rules everyone understood even if no one wrote them down.

One of those rules was simple: Harlem was Bumpy Johnson’s world.

Whether you believed the legends about him or you only knew the practical truth, his influence was real. He represented a kind of street order that was equal parts feared and respected. He understood money, loyalty, reputation, and timing. And in the economy of the underworld, timing was everything.

That night, according to the story that would spread through the city like smoke, a rival crew decided to test what “everything” really meant.

They were known in some circles as the Westside Boys, a rough outfit tied to the far west neighborhoods. A mix of backgrounds, a reputation for intimidation, and a leader whose temper had become part of his brand. The details vary depending on who tells it, but the core claim stays the same: they weren’t content to stay in their lanes. They wanted a slice of a contested strip of territory where money changed hands quickly and quietly, and they believed they could take it by force.

The spark, as the story goes, wasn’t glamorous. It wasn’t a dramatic betrayal or a cinematic shootout. It was business.

A local numbers runner worked a boundary area where different crews claimed influence. For months, things stayed relatively steady. Then the pressure started. A message was delivered. A warning followed. And soon, a personal dispute became a public challenge.

People in that world understood escalation in a specific way. The first message was a test. The second was a dare. The third was war.

Bumpy’s response, in the version of the story that Harlem repeated for years afterward, was controlled at first. He didn’t rush. He didn’t posture. He answered in the language that street organizations had used for decades: proportional consequence. Enough to be clear, not enough to be reckless.

But the rival leader didn’t read it as proportional. He read it as disrespect.

And in an era where race and power collided constantly, the insult wasn’t only territorial. It was symbolic. It was personal.

So the rival crew allegedly decided to do something that would end the argument permanently: remove Bumpy Johnson as a factor.

Not negotiate. Not pressure. Not divide the profits.

End it.

The plan hinged on something older than any weapon: a setup disguised as a meeting.

The meeting was supposed to be neutral, quiet, “professional.” That word always sounded clean until you remembered what it really meant in that environment. Neutral didn’t mean safe. It meant the danger was simply being managed out of sight.

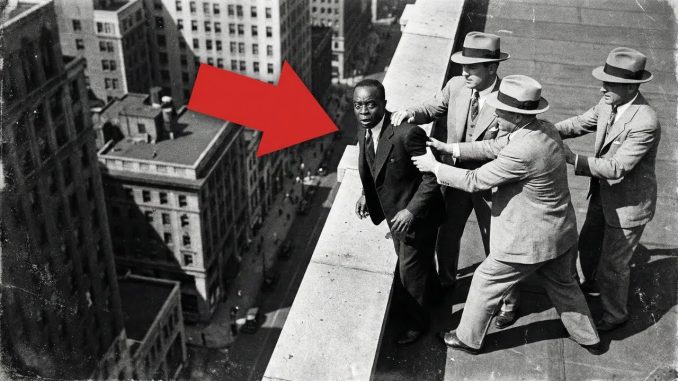

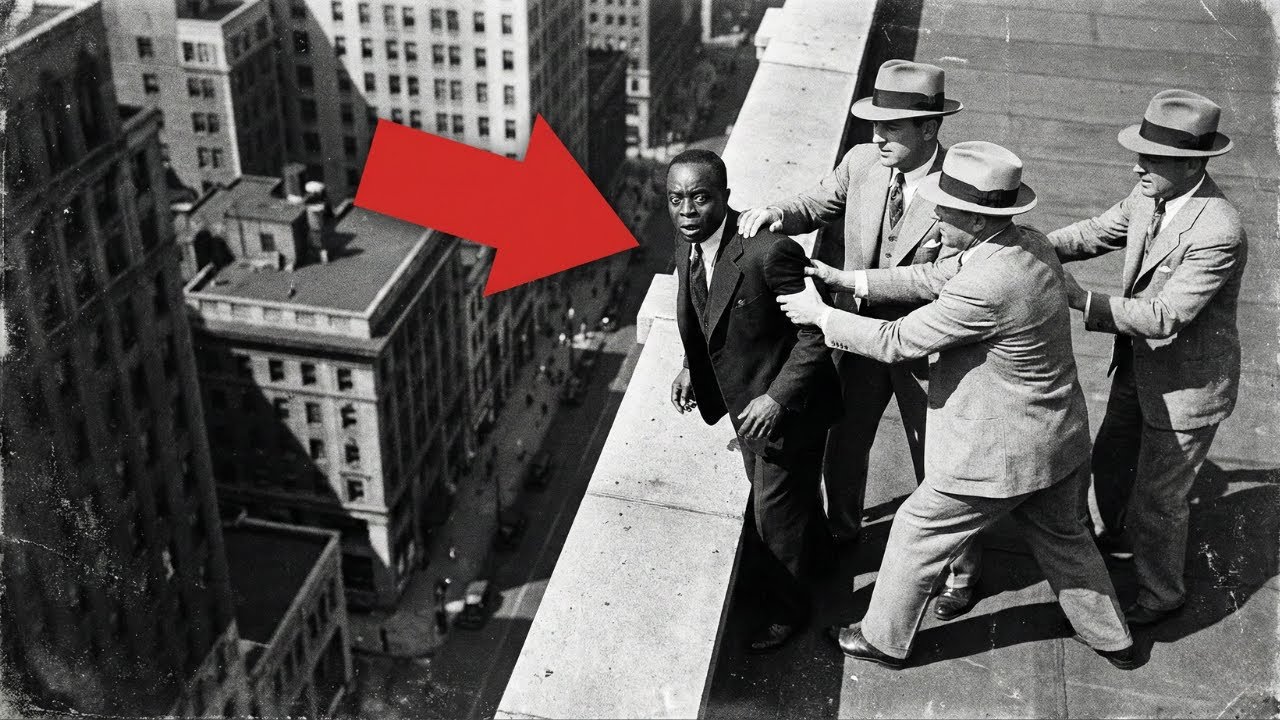

The location, the story claims, was a modest building where access could be controlled. Rooftop, fire escape, limited exits. The kind of place where a man could be boxed in without a single passerby understanding what was happening above their heads.

Bumpy arrived alone.

That detail matters because it’s the kind of choice that reveals how these men thought. When you accept a meeting alone, you’re either signaling confidence or accepting risk as a cost of doing business. Either way, you’re telling the other side you won’t show fear.

He was a few minutes late, which in that world could be strategy. Timing was leverage. Being late meant you were not being pulled like a puppet by someone else’s schedule.

When he reached the roof, he didn’t find a negotiation table.

He found a semicircle.

Men positioned carefully. Faces hard, bodies angled, silence heavy. Not a conversation. An ambush that didn’t bother to hide itself once the door behind you had closed.

The leader greeted him like a man already celebrating.

And then came the moment that turned the story into legend: Bumpy didn’t panic. He didn’t beg. He didn’t bargain the way the rival crew expected.

He looked at the setup and understood something instantly. On that roof, the outcome had already been decided by the people who invited him there. The only thing left was the timeline.

In some tellings, that’s when he forced the timeline forward.

Instead of allowing the rival crew to drag out the intimidation, he stepped toward the edge as if to say, “If you’re going to do it, do it. Don’t perform.”

It’s hard to confirm what was said. It’s hard to confirm exactly how it unfolded. Stories like this are stitched together from rumor, street memory, and the way fear changes a witness’s sense of time.

But the next piece of the legend is the one Harlem never forgot.

He went over.

Four stories down.

A drop that, by any reasonable expectation, should have ended the story.

People below reacted the way people always do when something impossible interrupts an ordinary night. Some froze. Some shouted. Some ran to get help. Some turned away, because turning away was how you kept yourself alive in a neighborhood where attention could be dangerous.

And then, according to the tale, came the twist that made the whole city lean in: he survived.

Not as a miracle that left him untouched, but as a survival that left no doubt he had been pushed beyond ordinary limits and still refused to disappear.

If you want to understand why this story lasted, it’s not because people enjoyed the violence. It’s because the survival flipped the psychological math.

The rival crew’s plan depended on finality.

If Bumpy was gone, Harlem would splinter. Smaller crews would fight over pieces. Money would leak. Confidence would fracture. That chaos would make it easy for outsiders to wedge themselves in, to buy loyalty cheaply, to pick off blocks one by one.

But survival does something powerful.

Survival turns a hit into a declaration of war.

It turns a plan into a mistake.

Because now the target isn’t just alive. He’s alive with a story that makes him bigger than before.

In the version that Harlem repeated, Bumpy refused to go to a hospital. That choice also fits the logic of the time. Hospitals meant records. Records meant questions. Questions meant police. And police attention didn’t just threaten you, it threatened everyone connected to you.

More than that, if word spread that he was vulnerable in a public place, the rival crew would have a second chance to finish what they started. In that world, the second attempt is often quieter than the first.

So the story says he disappeared from the sidewalk and into the shadows long enough to make a call.

Or rather, to have someone make it for him.

A message delivered to one of his most trusted lieutenants: come now, bring men, bring whatever you need, and bring it fast.

Two hours.

That detail is repeated with almost ritual precision in the storytelling, because it turns the narrative into something more than retaliation. It becomes a statement about organization.

People assume street power is random. Emotion-driven. Chaotic.

But the most dangerous operators were not chaotic at all. They were managers. Strategists. Logistics experts who understood that control over people mattered more than any single act of force.

And if the story is to be believed, that’s exactly what happened next.

Harlem mobilized.

Not slowly. Not over days. Not after debates and arguments.

Fast.

Men who might have been scattered across nightclubs, gambling rooms, and late-night kitchens suddenly became a unit. Word traveled the way it always traveled in neighborhoods built on tight networks: through pay phones, back rooms, and trusted mouths that didn’t waste syllables.

The message wasn’t subtle.

This wasn’t a dispute anymore.

This was a line crossed.

The rival crew had not only attacked a man, they had insulted a neighborhood. They had tried to rewrite the rules of territory in a way that would make Harlem look weak.

And Harlem, in the story, answered the only way it believed would be understood.

What followed is often described as one of the bloodiest nights in that era’s underworld, but it’s important to say this clearly: many details are impossible to verify with certainty, and versions differ depending on the source. Some accounts exaggerate numbers. Some compress timelines. Some sharpen drama to make it more cinematic.

What remains consistent is the claim that multiple rival locations were hit in a coordinated fashion, fast enough to overwhelm any response.

A few minutes.

Several sites.

A message delivered not through a single confrontation, but through simultaneous shock.

The legend emphasizes precision: teams assigned, targets chosen, timing synchronized. The purpose wasn’t randomness. It was erasure.

Not “fight us.” Not “back off.”

It was “you don’t get to exist here anymore.”

Police, according to the narrative, arrived after the fact. That also fits the reality of coordinated events: by the time a response organizes around one incident, another is already unfolding elsewhere.

And in an environment where witnesses had every reason to protect themselves, clear statements would have been rare. People who knew what happened would have measured their words with fear and survival.

Officially, stories like this often end with “unsolved.” Not because nobody had suspicions, but because suspicion isn’t evidence, and evidence doesn’t always survive a community that has decided silence is safer than truth.

The immediate result, in the legend, was simple: the rival crew collapsed. Leadership gone, confidence broken, operations scattered. The name that had carried intimidation the week before suddenly became a name people avoided saying out loud.

And then came the longer consequence, the one that mattered most to Harlem.

Harlem wasn’t open.

Harlem wasn’t vulnerable.

Harlem was now, if anything, more sealed than before.

Because survival plus response becomes mythology, and mythology becomes deterrence.

If you’re a smaller crew watching from the sidelines, you don’t see the human cost first. You see the lesson: if you try to make an example of the man running Harlem, Harlem will make an example of you.

That’s how reputations become armor.

Not because they make you invincible, but because they make everyone else calculate the cost of trying.

In the months after October 1952, the story says Bumpy eventually reappeared publicly. Not with fanfare. Not with speeches. Just visible enough for everyone to draw the only conclusion that mattered: he was still here.

In street politics, presence is a language.

You don’t have to announce victory if your body is sitting in the same seat it always sat in, in the same neighborhood, under the same lights.

The rival side’s attempt to remove him became the opposite of what they wanted.

Instead of shrinking his influence, it hardened it.

Instead of making Harlem easy to take apart, it reminded Harlem why cohesion mattered.

Instead of creating fear around him, it created fear around anyone who dared challenge him.

And that fear didn’t require constant violence to maintain. It required only memory.

This is where the story shifts from an incident into a broader reflection on how power worked in that era.

People imagine the underworld as impulsive men making reckless decisions in the heat of anger. That happens, sure. But the operators who lasted weren’t fueled by impulse alone. They were fueled by structure. They survived because they built systems. They understood that territory wasn’t just streets. It was relationships, revenue streams, and the belief that crossing certain lines would cost too much.

The rooftop legend endures because it captures that truth in a single dramatic arc.

A trap.

A fall.

A survival.

A response fast enough to feel unreal.

Whether every detail is literal or not, the story functions like folklore with teeth. It explains how Harlem perceived itself: a place where outsiders could visit, but not invade. A community where injustice wasn’t abstract, it was lived. A neighborhood where respect wasn’t performative, it was enforced by the shared understanding that people would not be treated as disposable.

It also carries a darker lesson: when official systems fail to protect communities, communities build their own systems. Those systems may not be lawful. They may not be fair. But they are often effective, and effectiveness is what keeps them alive.

There’s another reason the story has survived: it contains a kind of narrative justice. A man is targeted in a humiliating, public way. He refuses to be reduced. He survives. He answers. The attackers vanish from the board.

That arc is emotionally satisfying in a way that real life often is not.

Real life is messy. Real life leaves loose ends. Real life rarely gives perfect closure. So stories like this become a kind of closure the streets can hold onto, even if the official record stays incomplete.

Years later, writers and journalists would revisit incidents like the so-called Hell’s Kitchen night of violence, trying to separate exaggeration from reality. Some would point out how quickly myth grows around real events. Others would argue that the absence of clear records doesn’t mean the absence of truth, only the absence of documentation.

Either way, the rooftop story stayed where it always lived best: in the mouths of people who understood what it meant.

Don’t mistake a quiet man for a weak one.

Don’t confuse a neighborhood’s patience for surrender.

And if you gamble on humiliating power, be prepared for the kind of consequences you can’t control.

In the end, the legend isn’t really about a rooftop or a fall.

It’s about a moment when a rival crew tried to turn Harlem into an opportunity and instead turned it into a warning.

A warning written in timing, organization, and the cold reality that in some worlds, survival is not the finish line.

It’s the opening move.