The Iron Badge: Bass’s Silent War Against the Past

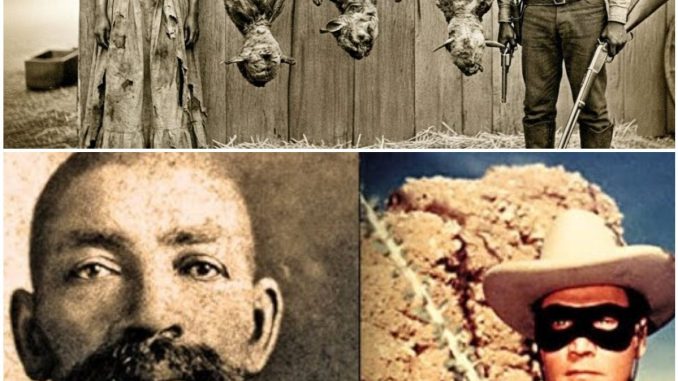

The photograph does not announce its importance.

It does not dramatize its subject or demand attention.

It simply waits.

A man stands with a rigid calm that feels earned rather than performed, his posture shaped by years of restraint rather than comfort. His eyes do not search the lens for approval. They hold it steady, as if measuring the future as carefully as the past. The badge on his chest reflects no pride, only responsibility. This is Bass, a man born into bondage who would become one of the most effective lawmen the American frontier ever produced, carrying with him not vengeance, but memory.

Bass entered the world in the early nineteenth century under a system that reduced human beings to ledger entries and inherited labor. His first lessons were not taught with books or kindness but through routine deprivation and enforced obedience. Every day unfolded within a structure designed to erase individuality and replace it with compliance. Family ties were treated as temporary inconveniences. Identity was something assigned, not chosen.

For those held in bondage, fear was not episodic. It was constant, ambient, woven into the rhythm of daily survival. The possibility of separation, punishment, or sudden relocation shaped behavior more than any spoken rule. Bass learned early that attentiveness was not curiosity but protection. Listening, observing, anticipating—these were not talents; they were necessities.

The system surrounding him was sustained not only by physical control but by paperwork. Ownership documents, transaction records, and contracts carried the authority of law while obscuring the moral cost beneath ink and seals. Bass grew up understanding that written words could shape lives more decisively than spoken ones. This awareness would later define how he approached justice.

The upheaval of the Civil War disrupted the rigid structures that had confined him. Amid uncertainty and movement, Bass found an opening where one had never existed before. His escape from bondage was not theatrical. It was careful, patient, and deliberate, shaped by years of knowing when to move and when to wait. Freedom did not arrive as a celebration. It arrived as exposure.

The frontier offered opportunity, but it also demanded adaptation. Law was inconsistent, authority uneven, and survival often depended on judgment rather than protection. Bass entered this environment with skills developed under pressure: navigation without maps, tracking without trails, endurance without recognition. These abilities were not romanticized talents. They were survival strategies refined over decades.

In the West, Bass encountered a different form of contradiction. The same nation that had permitted his bondage now offered him a badge. Becoming a U.S. Deputy Marshal placed him within an institution that had once excluded him entirely. The irony was not lost on him. He understood that authority could be temporary and conditional, especially for someone who carried the visible markers of a history many preferred to forget.

Bass did not treat his role as symbolic. He treated it as functional. The law, when applied consistently, could interrupt cycles of abuse and exploitation that had long operated without consequence. He pursued fugitives not with spectacle but with persistence, relying on observation, patience, and an understanding of human behavior shaped by experience rather than theory.

His effectiveness did not come from aggression. It came from reliability. He learned landscapes as thoroughly as he learned people, recognizing that both left patterns. He understood how fear influenced decisions, how desperation altered judgment, and how those accustomed to control often underestimated quiet resistance.

The frontier was not free of prejudice. Even with a badge, Bass navigated suspicion, hostility, and attempts to undermine his authority. Yet he remained consistent. He did not seek admiration or challenge hierarchy openly. He let outcomes speak. Each successful arrest reinforced a truth many found uncomfortable: competence does not require permission.

Alongside him in the photograph stands a woman whose presence carries equal significance. Her expression reflects endurance rather than triumph, resilience rather than relief. She represents the countless individuals whose survival depended on networks of trust rather than formal protection. Women like her preserved information, maintained community ties, and carried histories that official records ignored.

Their collaboration was not formalized, but it was essential. Knowledge traveled through observation, shared routes, and whispered warnings. Families seeking safety relied on discreet guidance, not proclamations. Bass understood that justice extended beyond courtrooms. It lived in whether people could sleep without fear of sudden disruption.

As migration increased, so did attempts to exploit vulnerability. Debt schemes, false contracts, and coercive labor arrangements replaced older forms of control. Bass recognized these patterns. He knew that injustice rarely announces itself openly. It adapts.

His work increasingly involved preventing harm rather than reacting to it. Intercepting threats before they reached their targets, dismantling operations built on intimidation, and ensuring that those newly free were not forced into new forms of dependency. These efforts rarely appeared in headlines, but they altered lives.

The Oklahoma Territory, where Bass operated extensively, functioned as a crossroads of opportunity and lawlessness. Former power holders sought to reassert influence through informal means. Bass understood that enforcing the law here required more than authority. It required credibility.

He carried with him the memory of a system that had claimed legality while committing injustice. That memory guided his restraint. He did not confuse power with purpose. The badge was not a weapon. It was a tool.

When conflicts escalated, Bass responded with strategy rather than force. He anticipated movements, studied behavior, and allowed adversaries to reveal themselves. His approach reduced unnecessary confrontation and preserved life. This discipline was not softness. It was precision.

By the late 1870s, Bass had become a stabilizing presence in regions where instability had been the norm. Families recognized him not as a legend but as a constant. Someone who arrived when needed and left quietly when the work was done.

The frontier changed as railroads expanded and governance became more centralized. Bass adapted without nostalgia. He did not romanticize the past, nor did he trust progress blindly. He measured change by its impact on those with the least protection.

Even as his reputation grew, Bass remained aware of its fragility. Shifts in policy or leadership could undermine years of work. He prepared for this by ensuring that his actions created structures rather than dependencies. He trained others, shared methods, and reinforced the idea that justice required participation, not heroism.

The final years of his service were marked by reflection rather than retreat. Bass understood that his role existed within a larger continuum. He was not ending injustice. He was interrupting it where he could.

The photograph captures this understanding. It does not depict victory. It depicts vigilance.

Bass did not seek to erase the past. He refused to be governed by it. His life demonstrates that accountability does not require rage, and resistance does not always announce itself loudly. Sometimes it stands quietly, badge visible, eyes steady, waiting for the next task.

The frontier remembers him not because he embodied myth, but because he practiced consistency in a landscape defined by extremes. He showed that law, when applied with integrity, could be a corrective rather than a tool of domination.

The iron badge he wore did not grant him authority. It marked the responsibility he accepted.

And that responsibility, carried without spectacle, reshaped the ground beneath him more enduringly than any legend ever could.