The photograph arrived in Sarah Chen’s office wrapped in brown paper and silence.

No return address. No note. Just an eighteen sixty-three daguerreotype sealed inside a velvet-lined case, its silvered surface dulled by time but still eerily intact. Sarah almost didn’t open it. After ten years as a forensic historian, she’d learned to trust the small instinctive warnings that crept in before trouble. But curiosity—her oldest vice—won.

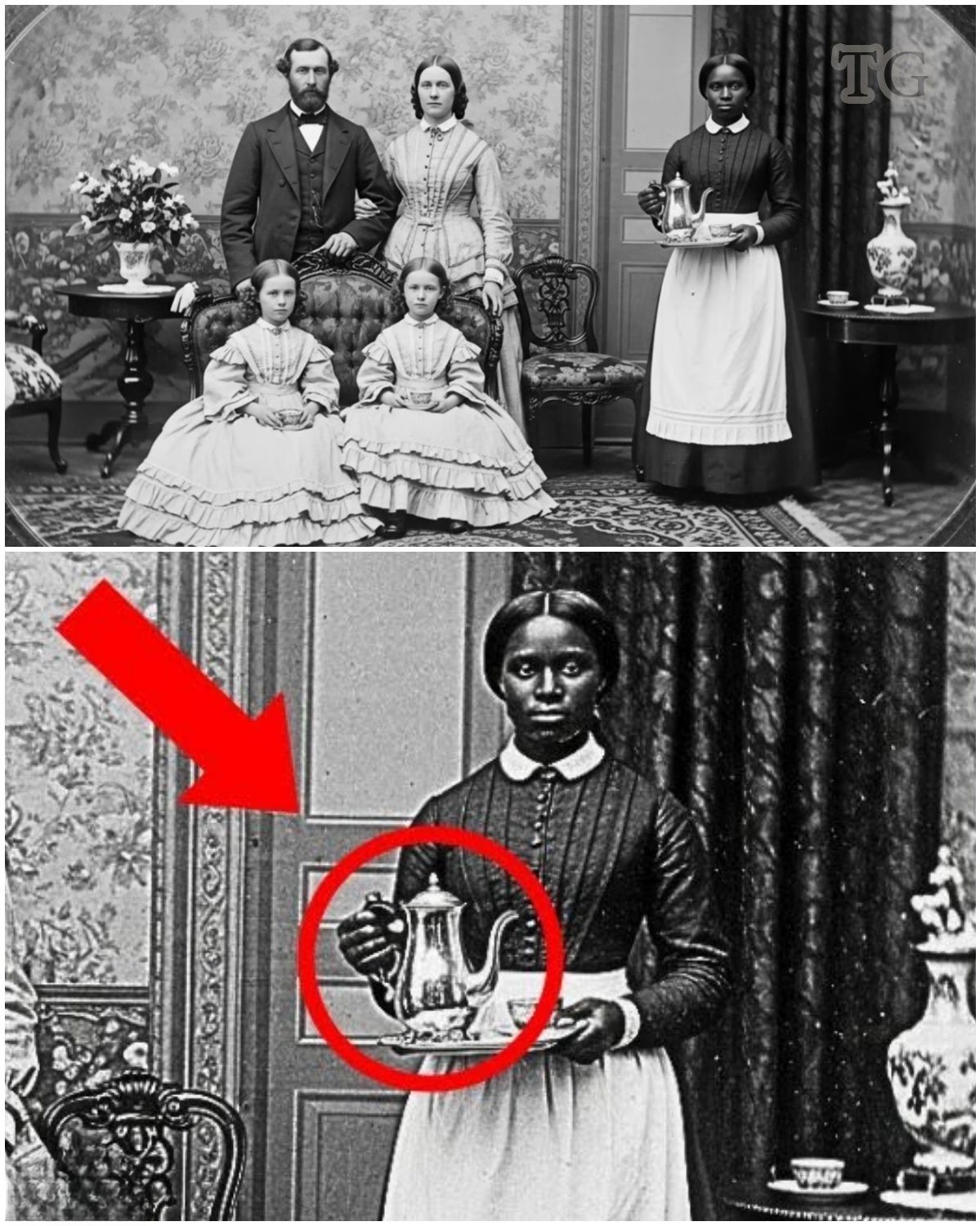

The image revealed a family frozen in Victorian composure: a man standing confidently behind his seated wife, two young daughters arranged symmetrically in front of them. Wealth, order, control. The usual story.

Except for the fifth figure.

A young Black woman stood slightly apart, holding an ornate silver tea service. She wasn’t blurred or hidden. She wasn’t placed at the edge. She was centered—deliberately included.

Sarah leaned closer.

The family smiled the way people did when portraits took minutes to expose—fixed, practiced, strained. But the woman holding the tea smiled differently. Hers was smaller. Contained. Her eyes were sharp in a way daguerreotypes rarely captured.

Not fear.

Not obedience.

Certainty.

Sarah felt it then—the familiar prickle at the base of her neck. The photograph was hiding something, and it wanted to be found.

On the back of the frame, barely visible beneath oxidized ink, was a single line:

The Whitmore Family, Richmond, Virginia. April fourteenth, eighteen sixty-three. Final Portrait.

Final.

Sarah checked the date twice.

The next three hours vanished into archives. The Whitmore name surfaced almost immediately in Richmond papers, dated April fifteenth.

“Prominent Household Found Deceased Under Mysterious Circumstances.”

Four bodies. Signs of violent convulsions. Suspected poisoning. Arsenic.

By April twentieth, the narrative had sharpened.

“Slave Woman Vanishes — Prime Suspect.”

Her name was Grace. Twenty-six. House servant. Literate. Known for her tea.

Sarah closed her laptop and stared back at the photograph. Grace’s eyes seemed to meet hers now, as if time had thinned just enough to let something pass through.

The case had been closed in eighteen sixty-three. But Sarah knew better. Closed cases were rarely finished ones.

The first twist came three days later, hidden inside a misfiled probate ledger.

Sarah had contacted Marcus Webb, a genealogist specializing in antebellum records. When he called back, his voice was tight, controlled in the way people sounded when anger had nowhere to go.

“She wasn’t born enslaved,” he said.

Sarah didn’t respond. She’d learned that silence often encouraged the truth to keep talking.

“Grace’s full name was Grace Morrison. Born free in Pennsylvania. Kidnapped in eighteen fifty-five. Sold south.”

The words landed heavily.

Marcus sent scanned documents—free papers, newspaper notices, letters from a father who never stopped searching. James Morrison, a barber, literate, persistent. He’d traveled to Richmond twice, tried to buy his daughter’s freedom.

Each time, the Whitmores refused.

Sarah reread the photograph’s inscription. Final portrait.

It wasn’t commemorative. It was transactional. Property, documented before disposal.

That night, Sarah dreamed of silver.

The second twist came from a diary no one was supposed to read.

Margaret Hayes, a neighbor, had kept meticulous journals between eighteen sixty and eighteen sixty-three. Her entries were mundane until they weren’t.

“Found Mrs. Whitmore beating her girl Grace today,” one entry read. “She bore it without sound. This seemed to enrage Mrs. Whitmore further.”

Another described punishments—starvation, isolation, cold. Grace slept under the stairs. Worked before dawn. Served tea with perfect precision.

“She watches everything,” Margaret wrote once. “It unsettles me.”

The final entry before the photograph froze Sarah in place.

“A man claiming to be Grace’s father arrived with a large sum. Richard Whitmore laughed at him. Threatened arrest. Later told me Grace would be sold south as punishment.”

Sold to a plantation.

Sarah felt the pieces shift.

Grace had four days between that threat and the photograph.

Four days to choose between erasure and action.

The third twist didn’t come from paper. It came from chemistry.

Dr. Rebecca Torres, a toxicologist, studied the symptoms listed in the eighteen sixty-three reports.

“White arsenic,” she said without hesitation. “Slow. Painful. Requires planning.”

“Could it be hidden in tea?” Sarah asked.

Rebecca nodded. “Sweetened, creamed tea would mask the taste.”

Sarah glanced again at the photograph. Mrs. Whitmore’s hand hovered inches from a teacup. The silver teapot gleamed unnaturally bright.

“She would have known,” Sarah said. “Known what they’d suffer.”

“Yes,” Rebecca replied quietly. “Which means this wasn’t impulsive. It was resolved.”

The smile made sense now.

It wasn’t triumph.

It was finality.

But the most disturbing twist came last.

Arsenic hadn’t been stolen.

Sarah uncovered pharmacy ledgers showing repeated purchases—by Mrs. Whitmore herself. White arsenic. Laudanum. Mercury tonics. Enough poison to supply a small hospital.

Grace hadn’t needed to sneak or steal. The weapon had been handed to her daily, placed within reach by the people who trusted her most.

The Whitmores had curated their own ending.

Sarah believed she had the story.

Then she found the interview.

A former enslaved woman named Clara Washington, interviewed in nineteen thirty-six, spoke of helping a woman escape Richmond after poisoning her captors.

“She walked out while they were dying,” Clara said. “I hid her. I don’t regret it.”

Grace had escaped.

She’d reached Union lines. Reclaimed her name. Returned north. Married. Taught children.

The photograph wasn’t the end.

It was the hinge.

Sarah presented her findings six months later. The audience argued fiercely. Murder. Resistance. Innocence. Complicity.

Sarah didn’t resolve the debate. She never did.

But that night, alone in her office, she noticed something she’d missed.

Under magnification, beneath the reflective silver, was a faint distortion—almost invisible.

A reflection.

Not of the family.

Of someone standing behind the camera.

A sixth presence.

Watching.

Smiling.

Sarah leaned back slowly.

The photograph wasn’t finished speaking.

And for the first time since it arrived, she wondered whether Grace had truly acted alone—or whether the image itself had been part of something far larger, something still unfinished.

The silver surface darkened as the light shifted.

And Sarah realized the story had only just begun.