Lucky Luciano opened his door in 1950 and found something waiting on his doorstep.

Five heavy packages. Wrapped tight. No return address he recognized. No delivery he was expecting. No explanation.

He stared at them for a long moment, then carried the first one inside.

When he opened it, whatever he saw made him shut the door, call a meeting, and swear to his inner circle that no one under his banner would test Harlem again.

Because those five packages weren’t gifts.

They were a message from Bumpy Johnson—delivered in the only language the underworld never misunderstands.

And to understand why Luciano reacted the way he did, you need to understand the power dynamic between Lucky Luciano and Bumpy Johnson in 1950.

By 1950, Luciano was living in exile. The U.S. government had deported him to Italy in 1946. Officially, he was out of the game.

In reality, he still had influence. He still had people in place. Frank Costello handled day-to-day decisions. Meyer Lansky watched the money. Vito Genovese waited in the wings. And the right conversations still flowed across the Atlantic to “Charlie Lucky” in Naples.

But there was one neighborhood in New York that his network couldn’t simply absorb.

Harlem.

Bumpy Johnson controlled Harlem. Had controlled it since the 1930s. Numbers operations, policy banks, street-level protection—everything ran through Bumpy’s system. And Bumpy didn’t answer to the Italian families.

He didn’t pay tribute. He didn’t ask permission. He didn’t pretend.

That independence irritated Luciano’s lieutenants—especially Genovese.

During a transatlantic phone call in January 1950, Genovese laid it out bluntly.

“Harlem is making millions and we’re not seeing a dime.”

Bumpy, Genovese argued, had an old understanding with them: they stayed out of Harlem, and Bumpy stayed out of their territories.

“That understanding was made twenty years ago,” Genovese said. “Times have changed.”

“Bumpy hasn’t changed,” Luciano replied.

“Then maybe it’s time someone changes the situation.”

Luciano paused. He respected Bumpy. Always had. He understood that Bumpy’s reputation wasn’t a story people told for entertainment—it was a warning people repeated for survival.

But Genovese had a point too. Harlem represented money they weren’t touching and territory they didn’t control. And in that world, control wasn’t a detail. It was the whole game.

“What are you proposing?” Luciano asked.

“Let me send some people,” Genovese said. “Establish operations. Show presence. We don’t have to start a war. Just remind Bumpy he’s not untouchable.”

From Italy, everything sounded manageable. The risk felt theoretical. Luciano wasn’t on the ground. He wasn’t feeling the daily weight of Bumpy’s name in Harlem.

So he agreed—carefully.

“Send professionals,” he said. “No chaos. No unnecessary heat. And if this goes wrong, it’s on you.”

“It won’t go wrong,” Genovese promised.

But it did. In a way that made every man involved wish the call had never happened.

February 1950. Five men arrived in New York from Chicago and Detroit—experienced operators brought in for one purpose: to create a foothold in hostile territory.

Their names were Tony Bala, Vincent “Vinnie” Russo, Michael Delaney, Sal Martino, and Frank “The Hammer” Costanza.

Not Frank Costello. A different Frank. A different reputation.

These weren’t reckless kids chasing a fast score. These were disciplined men with long resumes—collection work, gambling operations, intimidation, enforcement. They knew how to move quietly, recruit locals, set up front businesses, and make a neighborhood feel their presence without drawing attention too fast.

The plan was methodical.

Phase one: establish three policy banks in East Harlem. Recruit local runners. Offer better payouts than Bumpy’s operation.

Phase two: approach businesses. Offer “protection” against future problems. Build a base of clients.

Phase three: expand—slowly, block by block—until Harlem was no longer independent.

The five men checked into a Midtown hotel, not Harlem. Too obvious. Too loud. They would commute in each day, scout, meet contacts, and map the terrain.

What they didn’t know was that Bumpy Johnson knew they were coming before they even settled into their rooms.

Bumpy had eyes everywhere—hotels, restaurants, stations, airports—people who looked ordinary by day and delivered information by night.

A porter at the hotel noticed the five men immediately: the expensive suits, the alert posture, the way they asked questions without asking questions. He made a phone call.

“Mr. Johnson,” he said, “five out-of-towners checked in. Chicago accents. Asking about Harlem.”

Bumpy thanked him and hung up. Then he made another call.

“Illinois,” he said, “I need you to follow five men staying at the Lexington. I want to know everywhere they go and everyone they talk to. Don’t approach them. Just watch.”

Illinois Gordon was one of Bumpy’s best surveillance men—patient, invisible, precise.

For three days, Illinois followed them. He watched them scout storefronts. He watched them approach locals. He watched them circle businesses like shoppers looking for a deal.

On the fourth day, Illinois reported back.

“They’re setting up policy banks. Three locations. 116th, 125th, and 135th. They’ve already recruited locals—promising better splits than yours.”

Bumpy listened without expression.

Then he asked one question.

“Do they know we’re watching?”

“No, boss. They’re confident. Acting like they already own the place.”

Bumpy nodded slowly.

“Let them set up,” he said. “Let them commit.”

Because Bumpy understood something that outsiders often missed: the moment someone believed they had a foothold, they stopped being cautious. They relaxed. They got predictable.

And in Harlem, predictable was dangerous.

February 14th, 1950. Valentine’s Day—an ironic date for what was coming.

The five men opened their first policy bank: a storefront that looked like a harmless social club. The front room was conversation and smoke. The back room was business.

They printed their own slips. Set their own odds. The cash started small but steady. A few curious locals. A few runners willing to test a new offer.

Tony Bala, the leader, called Genovese from a pay phone.

“We’re operational,” he said. “First location is running smooth. Locals are responding.”

“Any issues with Johnson?” Genovese asked.

“Haven’t seen him. Haven’t heard from him,” Tony said. “I think he’s letting it slide. Or he’s watching.”

“If he’s watching, he’s not doing anything,” Tony added. “We’re good.”

But they weren’t.

That same night, Bumpy called a meeting at Small’s Paradise. His core crew—men he trusted completely—sat in a tight circle while music played outside like nothing in the world could touch them.

“Gentlemen,” Bumpy said, “we have visitors.”

He explained: five men working under Genovese had opened a policy bank on 125th.

One of his men leaned forward. “You want us to shut it down?”

“No,” Bumpy said.

“I want you to let it run for three more days. Let them relax. Let them think they’re safe.”

His men exchanged looks. They understood what “safe” meant in Bumpy’s vocabulary.

“On the third night,” Bumpy continued, “we collect all five. Same night. No mistakes.”

“All five?” someone asked.

“All five,” Bumpy repeated.

This wasn’t just about competition. This was about a boundary. A line that had held for decades. A line that kept Harlem independent.

“You don’t come into Harlem without permission,” Bumpy said.

February 17th, 1950. 11 p.m.

The five men were leaving their storefront after a solid night. They were laughing. Confident. The kind of confidence that makes a man forget he’s standing in someone else’s territory.

Tony said it out loud.

“See? I told you Johnson wasn’t going to do anything.”

Vinnie chuckled. “Or he’s scared of Genovese.”

They walked toward their car, parked a couple blocks away.

That’s when the lights went out.

Not just street lights. Building lights. Windows. The whole stretch dropped into darkness so complete it felt planned.

Tony stopped mid-step.

“What the—?”

Shadows moved.

A moment later, men appeared from doorways, alleys, behind parked cars—ten, fifteen, twenty figures closing in from all sides.

Tony reached for his weapon.

“Don’t,” a voice said—quiet, close, and unmistakably calm.

Tony turned slowly.

Bumpy Johnson stood a few feet away, composed, not rushed, as if he had been waiting for this moment all week.

“Evening, gentlemen,” Bumpy said. “Welcome to Harlem.”

One of the five tried to run. He didn’t get far before he was stopped and pulled back. The others froze, realizing there was nowhere to go.

Bumpy walked around them the way a man inspects a situation he already controls.

“You boys are brave,” he said, almost conversational. “Setting up shop in my neighborhood without even asking.”

Tony found his voice. “We’re just businessmen.”

Bumpy smiled.

“Business,” he repeated, like the word amused him.

Then his expression changed—just slightly.

“You know what isn’t business?” he said. “Disrespect.”

He looked at each of them.

“You disrespected Harlem,” he said. “And now you’re going to help me deliver a message.”

“To who?” Tony asked, though he already knew.

Bumpy nodded.

“To the man who sent you.”

His crew moved quickly. The five men were disarmed, restrained, and taken away in separate cars.

They were driven for a long time—long enough for the city to feel far behind them. When they stopped, they could hear water and distant horns.

The docks.

An old warehouse.

Cold. Empty. Quiet.

The five men were placed in chairs, arranged in a circle, facing each other. Bumpy stood in the center. Around him, his men waited without speaking.

“Here’s what’s going to happen,” Bumpy said calmly. “Your boss is going to receive a delivery.”

“What kind of delivery?” one of them asked.

Bumpy didn’t answer directly. He picked up a phone, dialed, spoke briefly, then hung up.

“Your boss thought he could walk into Harlem and take what’s mine,” Bumpy said. “He was wrong.”

“We’ll tell him,” Tony said quickly. “We’ll tell him it was a mistake.”

Bumpy shook his head.

“Words don’t move men like Genovese,” he said. “He needs something he can’t ignore.”

Bumpy stepped toward the door, paused, and looked back.

“For what it’s worth,” he said, “this isn’t personal. It’s a boundary.”

Then he left.

February 20th, 1950. 6 a.m. Lucky Luciano’s safe house in Naples.

Luciano was still half asleep when the phone rang.

“Charlie,” Frank Costello said on the line, voice tight. “You need to get on a secure line.”

Luciano sat up.

“What happened?”

“The five men,” Costello said. “They never checked in.”

Luciano’s stomach tightened.

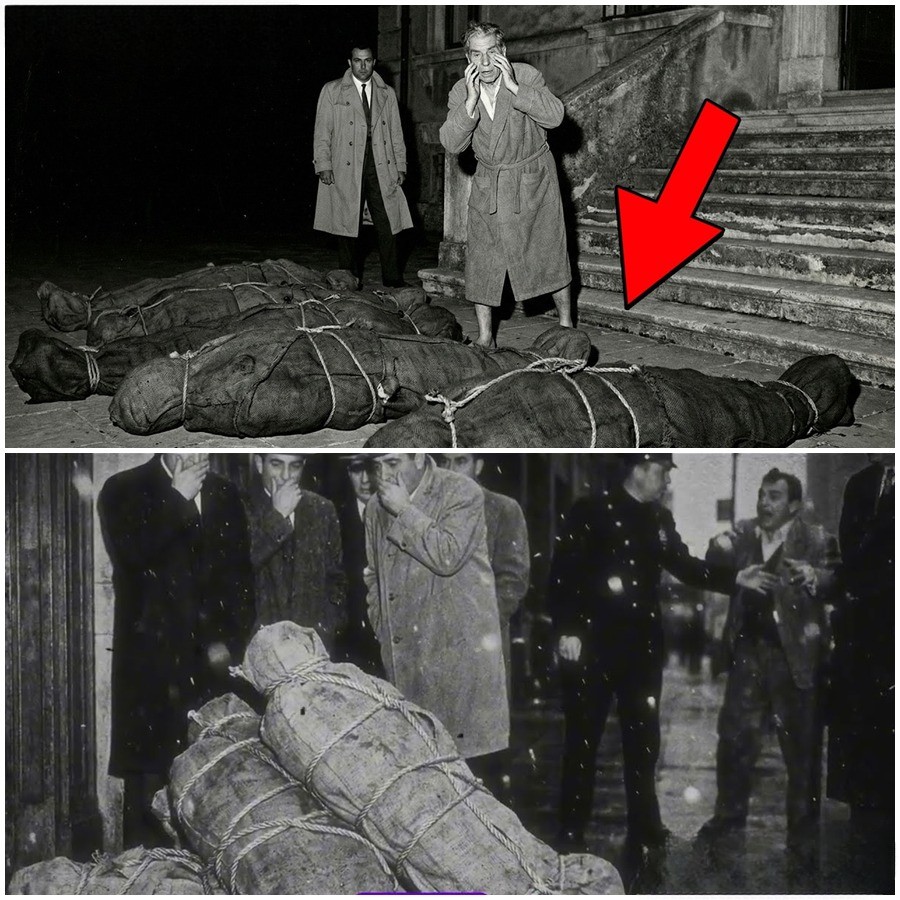

“And there’s something else,” Costello added. “Genovese got a delivery this morning.”

“A delivery?” Luciano repeated.

“Five packages.”

Luciano went still.

“What was in them?”

Costello didn’t answer immediately.

“It was… enough,” he said finally. “Enough that Genovese knew exactly who the message came from. Enough that no one needed further explanation.”

“And there was a note?” Luciano asked.

“Yes,” Costello said. “One word.”

“What word?”

“Harlem.”

Luciano closed his eyes. He understood.

He had underestimated the cost of crossing a boundary that existed for a reason.

“Call Genovese,” Luciano said quietly. “Tell him we’re done in Harlem. No more men. No more operations.”

“Genovese is talking about retaliation,” Costello warned.

“Then Genovese is about to make a second mistake,” Luciano said. “You don’t start a war with Bumpy Johnson on his own territory.”

Two hours later, Luciano called Genovese directly.

“Vito,” Luciano said, voice flat, “I heard about the delivery.”

“So we just accept this?” Genovese snapped. “We let him do this and walk away?”

“Yes,” Luciano said. “Because the message is clear. Harlem belongs to Bumpy Johnson. Not today. Not tomorrow. Not ever.”

“You’re afraid of him,” Genovese said.

Luciano’s voice didn’t change.

“I respect him,” he replied. “There’s a difference. And if you’re smart, you’ll respect him too—because the alternative is a war you cannot win.”

Genovese hung up angry and humiliated, but he followed orders.

No more men went to Harlem.

The story of the five packages spread through the underworld fast. Most people never learned the exact details, and they didn’t need to. The outcome was enough.

Five men were sent to Harlem.

A warning came back.

And Harlem remained off limits.

Years later, after Bumpy’s death in 1968, an old associate was asked what really happened.

He gave a small, grim smile.

“Bumpy didn’t do threats,” he said. “He did demonstrations.”

He paused, then added something people rarely said out loud about Bumpy Johnson.

“He wasn’t chaotic,” the associate said. “He was controlled. He didn’t act out of rage. He acted out of necessity. Because he knew if he let the first ones walk away, ten more would come. Then a hundred.”

And that was the point.

The packages weren’t about cruelty.

They were about a boundary.

In Harlem, Bumpy Johnson didn’t negotiate with intruders.

He reminded them—once—why the line existed.

If this story showed you why they called him the godfather of Harlem, hit that like button. Subscribe for more untold stories from the era when respect was earned with action, not words.

Drop a comment: do you think Bumpy went too far, or was this the only message that could have worked? And turn on notifications—next week we’ll tell the story of when Luciano and Bumpy finally spoke face to face after this incident, and how that conversation reshaped everything.

Because in Harlem, Bumpy Johnson didn’t make promises.

He made sure people remembered.