Harlem, 1948. Mount Olivet Baptist Church. Sunday afternoon.

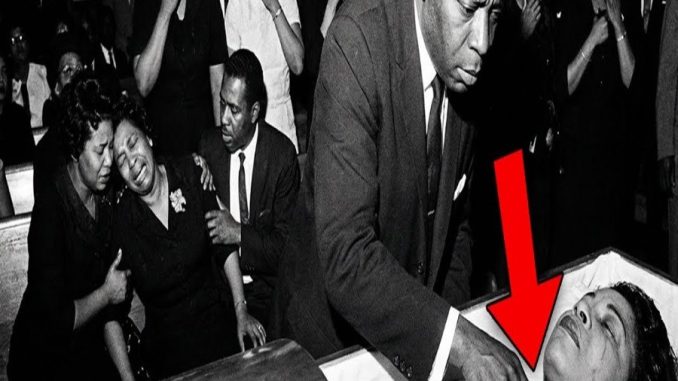

More than 400 people filled the wooden pews. The organ played softly. Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Jr. stood at the pulpit, mid-eulogy, speaking the kind of words a community reaches for when grief doesn’t make sense.

Then Bumpy Johnson rose from the second row.

It wasn’t dramatic. It wasn’t loud. But it changed the room instantly.

The organ faltered. The preacher paused. People stopped shifting in their seats. Even the children went quiet as Bumpy walked toward the casket—slow, deliberate, each step echoing against the church walls.

Most people in that room believed they were saying goodbye to a young nurse taken too soon.

Bumpy believed something else.

He reached the casket and looked down at Sadie May Washington in her white dress, her face carefully prepared, peaceful in the way funeral homes try to offer peace to the living.

Then Bumpy leaned closer.

Not to mourn.

To inspect.

He studied her neck, the line of her collar, the heavy powder sitting too thick for a simple Sunday service. He touched the makeup with two fingers and pulled his hand back.

Thick foundation coated his fingertips—more than anyone would normally use, concentrated in one place.

Bumpy turned his head slightly, eyes locking on the funeral director near the wall.

“Why is there so much makeup here?” he asked.

The funeral director’s face tightened. His hands hovered in the air like he didn’t know where to put them.

Bumpy didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t accuse anyone—yet. He simply reached down, eased the collar back, and exposed what the makeup had been trying to hide.

A pattern of marks—visible even from the second row—where no one expected marks to be.

The church reacted all at once.

Women gasped. Men stood. Someone near the aisle put a hand to their mouth. A few people turned away, not because of gore, but because the implication felt unbearable.

This wasn’t the clean, simple story people had been given.

And in that moment, the funeral stopped being a farewell.

It became a question.

A dangerous one.

Because if Sadie May Washington didn’t die the way officials claimed, then someone had lied—someone with power. And in Harlem, people knew what that usually meant:

A cover-up wasn’t a mistake.

It was a system.

To understand why Bumpy stood up that Sunday—and why it shook Harlem for weeks—you need to know who Sadie was… and why one quiet witness in the neighborhood refused to let her disappear into paperwork.

Who Sadie May Washington Was to Harlem

In September 1948, Harlem was built on endurance.

Families worked long hours for modest pay. Neighbors looked after each other because nobody else would. Community wasn’t a slogan. It was survival.

Sadie May Washington was one of the people holding that community together.

She was 30 years old, born on September 14th, 1918, on 139th Street. Her mother, Dorothy Washington, had taken in laundry for years to help put her daughter through nursing training at Lincoln Hospital.

Sadie graduated in 1941 near the top of her class. By 1948 she was known at Harlem Hospital as dependable to a rare degree—someone who stayed late, covered shifts, returned calls, and showed up even when she was tired.

People didn’t love her like a celebrity.

They loved her like you love the person who helped your child into the world. Like you love the person who calmed your fear in the middle of the night. Like you love the person who treated you with dignity when you felt invisible.

Every Sunday she sang soprano in the choir. Every Friday she visited older neighbors—bringing soup, checking on them, sitting long enough to make loneliness feel smaller.

Sadie never married. When people teased her about it, she’d smile and say something like, “Harlem’s my family.”

And to the community, that didn’t sound like a line.

It sounded like truth.

Sadie also had a younger brother, Marcus Washington, 28—her opposite in every way. He drifted. He gambled. He bounced between jobs and burned bridges.

By 1947, he left Harlem, claiming he’d found work in New Haven, Connecticut. What he found instead was debt—fast-growing debt under terms that turned a small loan into an impossible burden.

And that burden didn’t stay in Connecticut.

It followed him home.

The Link Nobody Wanted to Say Out Loud

Here is the part the neighborhood repeated in whispers: Sadie wasn’t just loved by Harlem.

She was known by Bumpy Johnson.

Not as a business relationship. Not as a transaction.

As family—real family, the kind you don’t write down.

Years earlier, long before 1948, Bumpy had been helped by the Washingtons in a moment when he couldn’t afford attention from hospitals or police. Harlem told that story like it was a sacred memory: a young Sadie and her mother stepping in when they didn’t have to.

Whether every detail was exactly as people repeated it didn’t matter as much as what the neighborhood believed:

Bumpy never forgot.

He quietly supported the family in hard times. He checked in. He showed up. He treated Sadie with something Harlem didn’t often get from powerful men—respect without conditions.

So when word spread that Sadie had died suddenly and officials called it “natural causes,” Bumpy felt the wrongness before he ever reached the church.

Young women don’t vanish overnight for no reason.

Not women like Sadie.

Not without someone asking questions.

The Night a Witness Wrote Everything Down

On Wednesday night—September 8th, 1948—Sadie left Harlem Hospital after a long shift and walked toward home.

Across the street, in a third-floor apartment, Mrs. Ella Brooks—an elderly neighbor who struggled with insomnia—sat by her window like she often did, watching the neighborhood settle into the late hours.

Mrs. Brooks noticed a car she’d seen more than once that week: a blue Buick with out-of-state plates. She noticed unfamiliar men. She noticed the way the car moved and waited, not like a visitor, but like someone watching.

Then she saw a moment that made her heart jump: Sadie pausing on the sidewalk, an interaction that turned tense, the kind of quick confusion that doesn’t belong on a quiet residential block.

Mrs. Brooks didn’t run outside. She didn’t shout from the window.

Not because she didn’t care.

Because she had lived long enough to understand something painful: when Black families called the police in the middle of the night, the response was often late, dismissive, or worse.

Instead, she did what careful witnesses do when they are afraid and still want the truth to survive.

She wrote.

Time. Location. Vehicle description. Plate number.

She folded the paper and tucked it somewhere safe.

When morning came and people said Sadie had been found dead, the neighborhood tried to accept the official explanation because the alternative was too heavy.

But Mrs. Brooks couldn’t.

She had seen enough to know the timeline didn’t sit right.

So she chose one person she believed could actually act.

And she delivered her information quietly.

Anonymous. Simple. Precise.

A note that didn’t beg.

A note that said: this didn’t happen the way they told you.

The “Accident” That Didn’t Add Up

By Thursday morning, the story circulating in the building was the same:

Sadie May Washington had passed away suddenly. The police report called it natural.

People wanted to believe it because grief is easier to carry when it has a neat label.

But details didn’t fit.

Sadie had been seen the night before. She had plans. She had responsibilities. She wasn’t known to be ill. And she wasn’t the kind of person who disappeared without someone noticing instantly.

When officers arrived that morning, they were supposed to treat the scene like a mystery until it was solved.

Instead—according to the legend—paperwork moved faster than questions.

A cause was written down. A case was closed. A family was handed an answer before they had even been given space to ask the right questions.

And then came the quiet pressure that always appears when someone wants a story to stay small:

Use this funeral home. Keep things calm. Don’t make this harder than it already is. Let the community grieve.

It sounded compassionate on the surface.

But in Harlem, people understood that “peace” was sometimes another word for silence.

The Funeral Director’s Fear

When Bumpy confronted the funeral director in the church, he didn’t threaten him.

He didn’t need to.

He asked one simple question that hit like a spotlight:

“Why is there so much makeup here?”

Because if you need to hide something, you hide it where eyes go naturally. You hide it where families look when they say goodbye. You hide it where grief will blur the focus.

The director’s reaction told the room everything.

Not proof. Not a confession.

But fear.

And fear is often the first honest thing someone shows.

Under pressure, the director admitted what he could without naming more than he had to: an officer had visited. Instructions had been given. The message had been clear—make it look peaceful, don’t invite questions.

The church didn’t need every detail.

They understood the shape of it.

Someone had tried to control what Harlem saw.

Bumpy refused to let that happen.

How One Moment Turned Into a City Problem

After the funeral interruption, the story says Bumpy did what he always did when he suspected betrayal:

He organized.

He asked for names. He asked for the chain of signatures—who responded, who filed the report, who approved the closure, who steered the family, who benefited from speed.

He followed the thread back to the source.

And in Harlem’s telling, that thread didn’t just lead to outsiders.

It led into the precinct.

Because corruption rarely announces itself with a banner. It hides in routine decisions: a box checked, a line written, a call not made, a witness not interviewed.

It hides in the sentence, “Nothing to see here.”

When community leaders and local press began to ask questions, the situation became too visible to bury quietly.

The story says city officials—fearing scandal—finally moved.

Not out of sudden virtue.

Out of necessity.

An internal review. A reopening. A real examination of what had been dismissed.

And once that door opened, more things spilled out than anyone expected.

The Fallout Harlem Remembered

In Harlem’s legend, the consequences came in waves.

Not all at once. Not neatly. But unmistakably.

Officers who had treated the case casually suddenly faced scrutiny. Supervisors were forced to explain why paperwork moved faster than investigation. People who thought they were protected realized protection disappears when the crowd is watching.

Some resigned. Some were reassigned. Some quietly vanished from the neighborhood they had once treated like territory.

The point Harlem took from it wasn’t that one man “won.”

The point was that a lie didn’t survive daylight.

Not when a whole church saw the same thing.

Not when a respected witness wrote down what she saw.

Not when a community decided silence was no longer safer than truth.

And not when Bumpy Johnson—a man who understood both fear and power—chose to make the question louder than the cover story.

What This Story Really Says About Harlem

People often repeat this story like it’s only about Bumpy.

It isn’t.

It’s about Sadie May Washington—the kind of person a community can’t afford to lose, the kind of person whose life matters even when paperwork says otherwise.

It’s about Mrs. Ella Brooks—the kind of witness history depends on, someone who didn’t have authority, only attention and courage.

It’s about the church—400 people breathing the same air, feeling the same shock, realizing together that something didn’t add up.

And it’s about a lesson Harlem learned repeatedly, in different forms:

When systems fail, communities either accept the failure… or build their own pressure until the truth becomes too heavy to ignore.

In 1948, Harlem chose pressure.

Sadie May Washington deserved that.

Her mother deserved that.

And every family who had ever been told to stay quiet deserved to see what happens when quiet ends.

Because the moment Bumpy stood up in Mount Olivet, the room understood something simple and permanent:

You can call something an accident.

You can stamp a paper and close a file.

But you can’t force 400 people to unsee what they saw.