On a quiet prairie morning, a Canadian farmer stepped out to inspect his fields and froze. The ground looked as though heavy machinery had rolled through overnight. Soil was overturned, crops uprooted, and along the edge of a frozen wetland sat something unexpected: a mound of cattails packed together like a natural shelter.

It was not human-made. It was built by pigs.

Over the last three decades, feral hogs in Canada have grown into one of the most unexpected wildlife challenges on the continent. Once dismissed as unlikely survivors in a northern climate, these animals have adapted in remarkable ways, reshaping farmland, waterways, and scientific understanding of how introduced species evolve.

How Feral Hogs First Appeared In Canada

The story begins in the late 1980s and early 1990s, when Canadian farmers imported European wild boars for meat production. At the time, interest in specialty pork was rising, and wild boars were seen as a promising agricultural investment.

When market demand declined, some animals escaped enclosures while others were intentionally released. Most people believed the harsh winters of the Canadian Prairies would prevent these pigs from surviving long-term.

That assumption proved incorrect.

According to research reported by National Geographic and Canadian universities, the animals not only survived but adapted. Over time, they bred with domestic pigs, creating a hybrid well-suited for cold climates, large litters, and diverse food sources.

What Makes These Hogs Different

Feral hogs belong to the species Sus scrofa, which includes both domestic pigs and wild boars. While these groups differ in appearance and behavior, they can interbreed, producing offspring with mixed traits.

In Canada, this combination resulted in animals with thick coats, strong bodies, and a surprising tolerance for extreme cold. Researchers have documented individuals weighing far more than what is typically seen in wild boar populations elsewhere.

Wildlife biologist Ryan Brook of the University of Saskatchewan describes these animals as unusually resilient. Their reproductive rates, combined with their ability to find shelter and food year-round, allow populations to expand rapidly.

The Science Behind “Pigloos”

One of the most fascinating adaptations observed is the construction of shelters commonly called “pigloos.”

Using cattails and vegetation from wetlands, feral hogs pile plant material into dome-like structures that trap heat and block wind. Snow collects on the outside, adding insulation. Inside, temperatures can remain significantly warmer than the surrounding environment.

This behavior has drawn interest from ecologists because it shows problem-solving and environmental engineering rarely associated with pigs in popular culture. It also explains how these animals survive winters previously thought impossible for their species.

Mapping The Spread Across Canada

For years, the presence of feral hogs went largely unnoticed. They are intelligent, primarily active at night, and skilled at avoiding human contact.

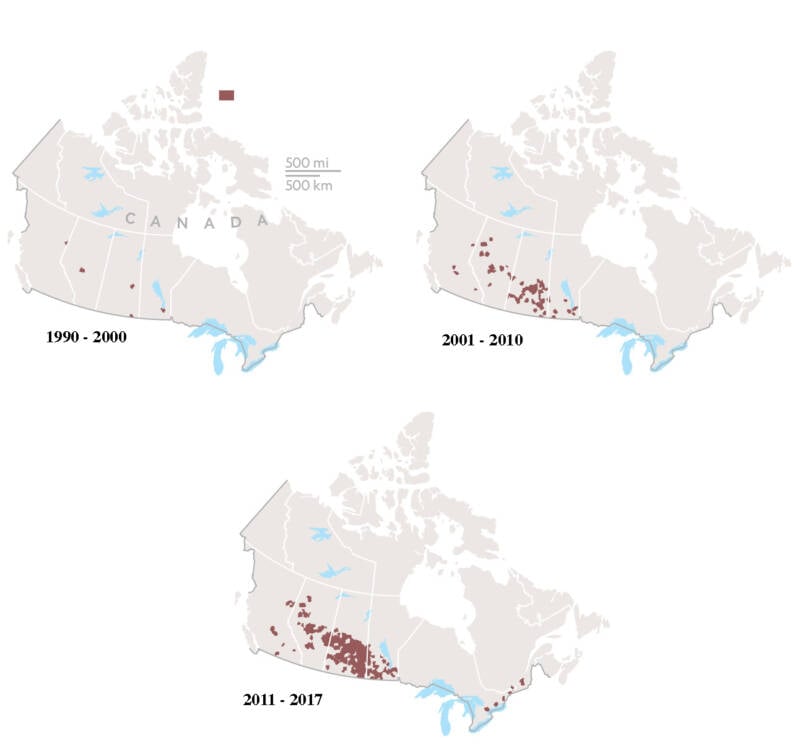

That changed when researchers began systematic tracking. Using trail cameras, GPS collars, and interviews with farmers and land managers, scientists mapped their movement over decades.

The findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, revealed that feral hogs had spread across multiple provinces, including Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba, and British Columbia. Their movement often follows waterways and watersheds, which provide food, cover, and travel routes.

Impact On Farmland And Ecosystems

Feral hogs are opportunistic feeders. They consume crops, roots, grasses, and small organisms found in soil. Their rooting behavior disturbs large areas of land, altering soil structure and vegetation growth.

Farmers often describe the aftermath as extensive and difficult to repair. Pastures, hay fields, and cropland can be affected in a single night.

Beyond agriculture, researchers express concern about wetlands and streams. When hogs wallow in shallow water, sediment is disturbed, and water clarity can change. Scientists emphasize that these environmental effects require careful monitoring rather than alarmist conclusions.

Cultural Perceptions Of Wild Pigs

Across cultures, wild pigs occupy a complex symbolic space. In folklore, they are often portrayed as stubborn, clever, and hard to control. In some traditions, they represent abundance and survival, while in others, disruption.

In Canada, the feral hog narrative challenges assumptions about what wildlife belongs where. These pigs are not native, yet they behave as though they have always been part of the landscape.

This tension between human intention and natural adaptation raises broader questions about responsibility, land management, and long-term ecological planning.

Why Cold Regions Became A Stronghold

Unlike feral pigs in the southern United States, which thrive in warm climates, Canada’s populations are densest in some of the coldest regions.

Scientists believe this occurred because colder areas offered fewer predators and less competition. Combined with their shelter-building behavior and high reproductive capacity, these conditions allowed populations to grow steadily.

Ironically, the very climate once expected to limit them became part of their success.

Scientific Perspectives On Long-Term Outcomes

Researchers stress that understanding feral hog behavior is key to managing their presence responsibly. Studies focus on movement patterns, population growth, and ecosystem interactions.

Dr. Ruth Aschim, who spent years documenting hog distribution, noted that many communities were unaware of nearby populations until research brought clarity. This lack of visibility contributed to delayed responses.

Rather than framing the issue in extreme terms, scientists advocate evidence-based strategies grounded in ecology, agriculture, and cooperation between landowners and conservation authorities.

A Broader Lesson About Human Decisions

The rise of Canada’s feral hogs is not just a wildlife story. It reflects how short-term economic decisions can have long-lasting environmental consequences.

Animals released without long-term planning do not simply disappear. They adapt, evolve, and reshape their surroundings in ways that are often unpredictable.

This story serves as a reminder that ecosystems respond to change with complexity, not simplicity.

Looking Ahead With Curiosity And Responsibility

Feral hogs are now part of Canada’s ecological reality. Whether viewed as a challenge, a lesson, or a case study in adaptation, they demand thoughtful attention rather than reaction.

Their “pigloos,” immense size, and resilience reveal how adaptable life can be when given opportunity. They also highlight the need for foresight when humans alter natural systems.

As science continues to study these animals, the goal is understanding, balance, and coexistence wherever possible.

Conclusion: What The “Super Pig” Phenomenon Teaches Us

The story of Canada’s feral hogs is ultimately about human curiosity meeting unintended consequences. It shows how nature responds creatively to new conditions, often in ways that surprise even experts.

By approaching the issue with patience, research, and humility, society can learn not only how to manage wildlife responsibly, but how deeply connected human actions are to the world around us.

Sometimes, the most unexpected stories emerge not from distant wilderness, but from our own fields, wetlands, and past decisions.

Sources

National Geographic

University of Saskatchewan Research Publications

Scientific Reports Journal

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

All That’s Interesting