Saturday, August 23rd, 1958. Idlewild Airport, New York. At exactly 3:47 p.m., a Pan American Airways flight lifted off the runway, bound for Havana, Cuba. Among the passengers was Herbert “Herby” Goldstein, forty-two years old, a certified public accountant who had spent the last seven years managing the financial affairs of Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson.

Herby traveled light, at least in appearance. He carried only two suitcases. One held clothing, toiletries, and personal items suitable for a tropical climate. The other contained something far more significant: approximately two million dollars in cash. This money had not been taken all at once. It had been quietly redirected over six months through falsified records, inflated operational costs, and carefully disguised transactions.

The plan had been years in the making. For nearly three years, Herby studied every aspect of the organization’s financial structure. He memorized cash flows, identified weak points in oversight, and created layers of protection—backup accounts, intermediary transfers, and trusted contacts abroad. He knew that if he ever made a move, it would have to be precise and final.

Cuba was not a random choice. In 1958, Havana was a destination for American expatriates, gamblers, and individuals seeking discretion. The political climate favored those with money, and cooperation with U.S. authorities was limited. Herby believed that once he arrived, he would be free to disappear into a comfortable life funded by money he felt he had earned.

He chose a Saturday deliberately. Bumpy Johnson was known to reserve weekends for family. Financial reviews were typically postponed until the following week. Herby calculated that it would take at least seventy-two hours for the missing funds to be noticed, analyzed, and understood. By then, he would be beyond reach—geographically and, he believed, practically.

What Herby did not know was that his calculations were already obsolete.

For nearly two months, Bumpy Johnson had sensed something was wrong. Certain expenses were higher than expected. Revenue appeared slightly inconsistent. Nothing blatant, nothing he could immediately point to, but enough to trigger his instincts. Years of experience had taught him that small discrepancies often pointed to larger problems.

Rather than confront Herby directly, Bumpy observed. He allowed the numbers to continue moving while quietly examining patterns. He waited.

The moment Herby’s plane left the ground at 3:47 p.m., Bumpy received confirmation that the move had finally been made.

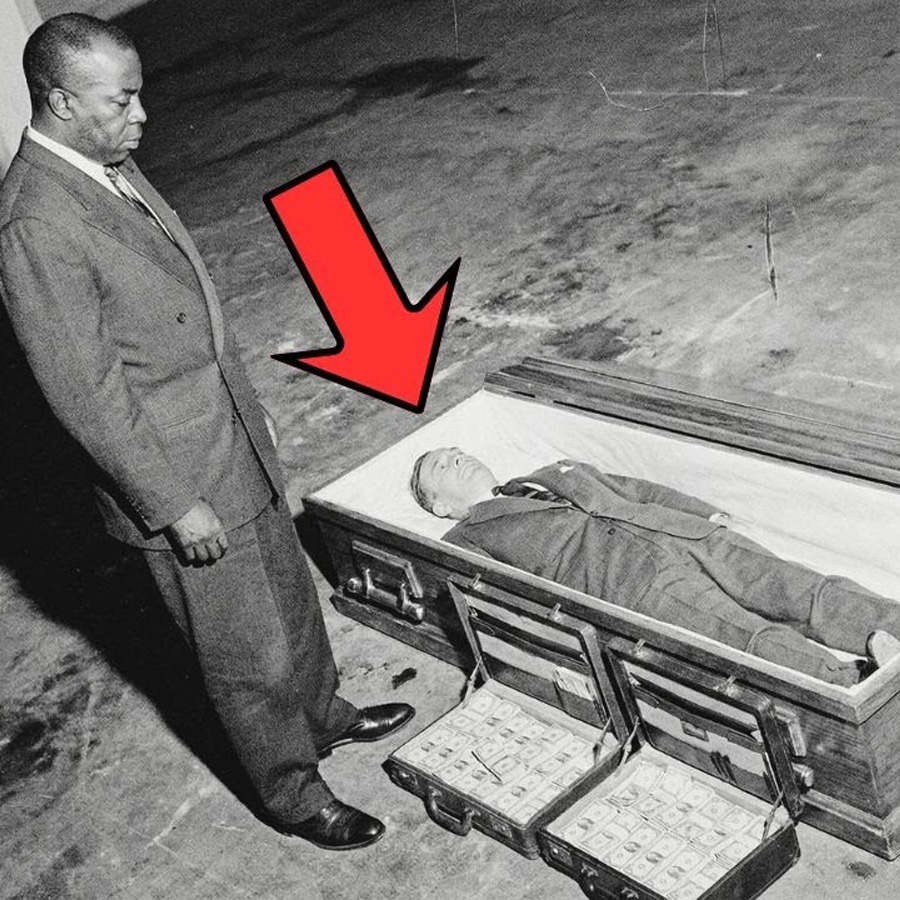

By 4:15 p.m., Bumpy’s associates had identified Herby’s destination. By 5:00 p.m., trusted contacts outside the United States had been alerted. And by 5:47 p.m.—exactly two hours after departure—Herbert Goldstein was no longer alive in a Havana hotel room. Arrangements were already underway to return his remains to New York in a sealed coffin, accompanied by a written message.

“Stole $2 million at 3:47 p.m.

Returned at 5:47 p.m.

Nobody steals from Bumpy Johnson. —BJ”

To understand how events unfolded with such speed, it is necessary to look back at the relationship between Bumpy Johnson and Herbert Goldstein.

They began working together in 1951. At that time, very few licensed professionals were willing to associate with a Black crime figure, regardless of compensation. The risks were significant, and the social climate offered little protection. Herby, however, saw opportunity. He was intelligent, discreet, and ambitious.

Bumpy rewarded loyalty generously. Herby earned $50,000 per year—a remarkable sum at the time. In return, he managed a complex web of financial activity: cash-based businesses, real estate holdings, and operations that required constant movement of funds while avoiding unwanted attention.

For seven years, Herby performed flawlessly. His records were thorough. His explanations were convincing. He earned Bumpy’s trust.

But over time, familiarity bred entitlement.

Herby watched millions flow through accounts he controlled. He began to compare his salary to the scale of the operation. He convinced himself that his role was undervalued. These thoughts grew quietly at first, then steadily, until they formed a plan.

He could not ask for more money. That would draw suspicion. Instead, he decided to take it gradually, in amounts small enough to avoid immediate detection but significant enough to accumulate quickly. Once he had enough, he would disappear.

He began in February 1958. Small adjustments. Minor expense inflations. Redirected payments. Each transaction was designed to blend in. By summer, the total approached two million dollars.

By June, Bumpy noticed.

He called Herby in for a discussion, asking him to explain specific expenses. Herby responded confidently, offering plausible justifications. Bumpy listened carefully. He did not accuse. He did not argue. But he remained unconvinced.

Instead, Bumpy sought confirmation.

He hired an independent auditor, Calvin Reed, from Chicago. Calvin had no prior relationship with Herby and no stake in the outcome.

“Review the last six months,” Bumpy instructed. “Quietly.”

Calvin spent weeks analyzing records. His conclusion was clear.

“Your accountant is diverting funds,” he said. “At least $1.8 million.”

The methods were sophisticated, but the evidence was undeniable.

Bumpy asked if the matter could be addressed legally. Calvin was blunt. A legal approach would expose everything. That option did not exist.

Bumpy accepted the reality. He chose patience over confrontation.

He instructed Calvin to monitor Herby’s activity closely. Bank transfers. Withdrawals. Travel arrangements.

In mid-August, the activity intensified. Funds were consolidated. Cash withdrawals increased. Airline tickets appeared.

“He’s preparing to leave,” Calvin reported.

Bumpy contacted his lieutenant, Marcus Webb.

“He’s running,” Bumpy said. “I want this resolved immediately.”

Arrangements were made. Contacts in Havana were alerted. Favors were called in.

On Friday, Calvin confirmed the final details. A flight scheduled for 3:47 p.m. Saturday. Arrival at 6:12 p.m. Two suitcases. Cash withdrawn.

Everything was in motion.

On Saturday afternoon, Herby boarded the plane. He wore his best suit, trying to appear relaxed. During the flight, he ordered a drink and allowed himself to believe the plan had worked.

At 6:12 p.m., the plane landed in Havana. Herby retrieved both suitcases. Everything appeared intact.

Then two men approached him by name.

They were calm, well-dressed, professional. One spoke English. They asked him to come with them.

Outside, a car waited. They drove to a well-known hotel. Inside a private room sat Santo Trafficante Jr.

The conversation was brief.

Herby attempted to explain. To negotiate. To offer the money back.

Santo checked his watch.

“Your plane landed thirty-five minutes ago,” he said.

Shortly after, the matter was concluded.

The process afterward was efficient. A coffin had already been prepared. The money was secured. The message was written exactly as instructed.

By Sunday morning, everything arrived in New York.

Bumpy examined the results and gave one final instruction.

“Make sure everyone sees it.”

Word spread quickly.

Herbert Goldstein had taken two million dollars. He had fled the country. He returned in a coffin.

No one attempted such a thing again.

Not accountants. Not attorneys. Not anyone connected to the organization.

The lesson was clear: distance did not guarantee safety. Time did not equal escape.

Herby had three hours between departure and consequence.

Three hours of freedom.

That was all.