The photograph should have been ordinary.

That was what unsettled Dr. James Mitchell the most.

It rested at the bottom of a cardboard box softened by time, wrapped in newspaper so fragile it cracked softly when touched. The ink from forgotten headlines had bled faintly through the paper, leaving behind ghosted words no one had read in generations. James had already spent most of the afternoon sorting through the remnants of a closed estate—church pamphlets, account ledgers, faded portraits of people whose names history never bothered to keep.

He nearly left the box untouched.

Then his fingers brushed against something cold.

Metal.

The unmistakable rim of a daguerreotype.

James paused. The object felt heavier than it should have been, as if it resisted being lifted. He carefully freed it from the paper, wiped the dust from the clouded glass with his sleeve, and leaned closer beneath the desk lamp.

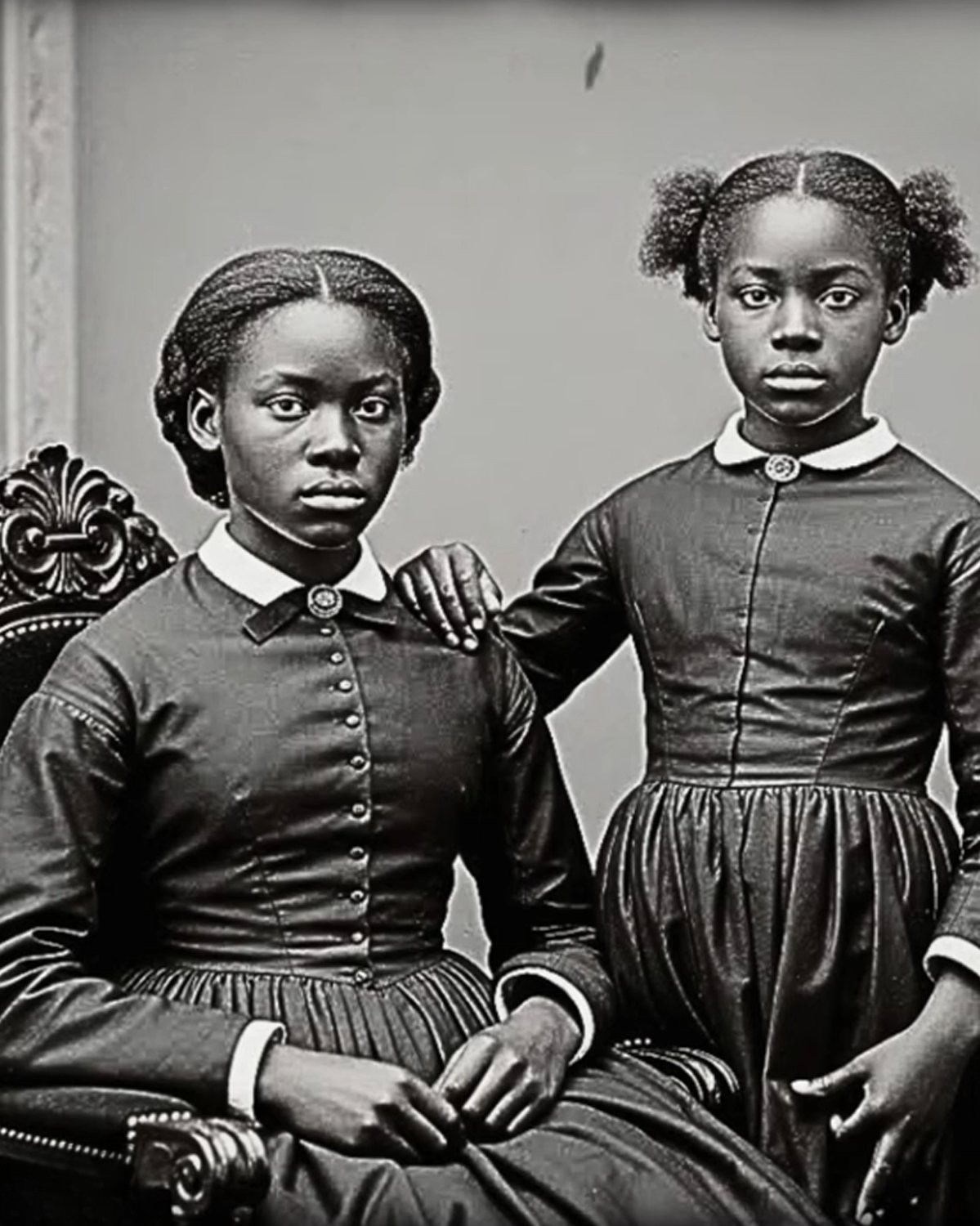

Two girls stared back at him.

They were Black, young, and dressed with deliberate care. This was not a casual image. The older sister sat upright in a carved wooden chair, her posture composed, her dark dress buttoned high to the neck. Her expression was calm, but not gentle—more measured, more aware. The look of someone who understood responsibility far beyond her years.

The younger girl stood beside her. She could not have been more than twelve. One hand rested lightly on her sister’s shoulder, a gesture meant to soften the formal pose. Her face was sharp and watchful, her lips pressed together as if holding back words she had been told never to speak.

James had studied thousands of Civil War–era photographs. He knew the stiffness required by long exposure times, the rituals of early portraiture, the way bodies were arranged to endure the stillness. This image followed all those rules.

And yet, it felt alert.

Alive.

He tilted the photograph closer to the light.

That was when he noticed the younger girl’s free hand.

It hung at her side, but it wasn’t relaxed. Her thumb and forefinger formed a near-perfect circle. The remaining three fingers extended upward, angled deliberately—not randomly, not casually.

James felt his breath catch.

The hum of the desk lamp suddenly felt too loud in the quiet archive room. He leaned closer, heart beating faster. He had seen that configuration before—not in photographs, but in sketches. In coded notebooks. In fragments of a system never meant to be preserved in plain sight.

This was not a pose.

It was a signal.

James stood so abruptly that his chair scraped loudly across the floor. He crossed the room to a locked cabinet—where he kept materials that rarely appeared in lectures or textbooks. He pulled out a leather-bound journal dated 1862, its pages yellowed and brittle with age.

It belonged to William Still.

James flipped through the pages until he found the margins filled with hurried sketches—hand positions, finger angles, symbols disguised as casual gestures. They were signals once used to identify safe locations, capacity limits, and directions without leaving written evidence.

The match was exact.

The circle: safe location.

Three fingers: three rooms available.

The angle: eastern district.

James slowly lowered himself back into the chair.

This was not a family portrait.

It was a message.

An announcement meant only for those who knew how to see.

And it had been mislabeled, ignored, and overlooked for more than a century.

On the back of the daguerreotype, written in fading ink, were only three words:

Sisters, Philadelphia, October 1863.

No names. No explanation.

Someone had wanted it that way.

The realization unfolded slowly. Why encode something so dangerous into a photograph—an object that could be seized, copied, misunderstood? Why trust an image that could fall into the wrong hands?

Then the answer became clear.

Plausible deniability.

To anyone else, it was simply a portrait. Two sisters. Nothing unusual. But to the right eyes, it quietly declared: shelter here. Safety here.

James felt the weight of that decision settle in his chest. Philadelphia in 1863 was crowded with informants and sympathizers on both sides of the conflict. Entire networks could collapse with a single mistake.

And yet someone had chosen to let a child carry the signal.

He looked again at the older sister’s face. The tension in her jaw. The directness of her gaze.

She knew.

She had allowed it.

Turning the photograph over once more, James noticed the photographer’s mark barely visible in the corner: J. Taylor, 247 South Street.

A lead.

The next hours blurred into focused searching—city directories, archived business records, university databases resurrecting forgotten names. By morning, James found himself standing in the special collections room of the Library Company of Philadelphia, watching an archivist place a slim ledger on the table.

October 1863.

The entries were precise. Dates. Names. Fees.

Then—

October 23rd, 1863. Two sisters portrait. Paid in full. Client: Ruth Freeman. 412 Lombard Street.

Lombard Street.

James pulled out a historical map. Lombard cut through the heart of Philadelphia’s free Black community—a known corridor of abolitionist organization.

The archivist returned with a city directory.

Freeman, Ruth — boarding house.

A boarding house.

James closed his eyes.

A boarding house meant movement. Guests. Turnover. A perfect cover.

Then came the detail that unsettled him most.

Ruth Freeman had been fourteen years old when she registered the property.

Fourteen.

An orphan, according to census records. Her parents had died during a cholera outbreak. The house had been inherited, debts unresolved.

And yet, the boarding house remained active for years.

Letters from the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society confirmed it—carefully worded references to “the Lombard station,” praise for “exceptional discretion,” notes about “items forwarded north.”

Then James found the final record.

Clara Freeman—the younger sister—had died in February 1864.

Cause: pneumonia.

Age thirteen.

The simplicity of the entry was unbearable.

As James dug deeper, church journals and benevolent society records revealed the rest. Clara had not only appeared in photographs.

She had been a courier.

Her youth made her invisible. She carried messages, directions, warnings—walking through winter streets while adults searched for dangers that never looked like her.

One line in a private ledger stopped James cold:

“The younger Freeman girl has proven invaluable. Her age shields her. Her resolve does not.”

The final mention came days before her death.

“She grows weaker, but insists on finishing the route.”

The photograph suddenly felt heavier than ever.

That carefully shaped hand gesture—so precise, so calm—had been made by a child who understood exactly what it meant. A child who knew the risk and chose it anyway.

Months later, James stood before a crowded auditorium. The photograph filled the screen behind him as he reconstructed the sisters’ story piece by piece. Ruth and Clara watched silently from the past.

The applause at the end felt distant.

After the lecture, an elderly woman approached him, holding a small daguerreotype of her own ancestor.

“Do you see anything?” she asked quietly.

James hesitated.

That night, alone in his office, he returned to the Freeman photograph one last time. He studied every shadow, every fold of fabric.

And then he noticed something he had missed.

Reflected faintly in the polished metal surface behind Clara’s hand was another shape.

Another hand.

Not belonging to either sister.

Someone else had been in the room.

Watching.

James felt a chill move through him.

The photograph, it seemed, was still telling its story.