5 Children Pose For Photo At Night. A Century Later, Experts Zoom In — And the Image Raises Alarming Questions

It began the way many historical mysteries do: with a photograph.

A quiet discovery. A faded image tucked inside a leather-bound album, forgotten for decades on a dusty archival shelf inside the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

At first, it appeared unremarkable. But when researchers examined it closely, they realized this photograph held a secret far more unsettling than anyone expected.

Dr. Evelyn Morse, a cultural historian specializing in late-Victorian domestic photography, came across the image while cataloging unclassified donations from a recently acquired private estate. The collection had once belonged to Dr. Harold Ketley, a physician known for his fascination with commemorative imagery from the turn of the century.

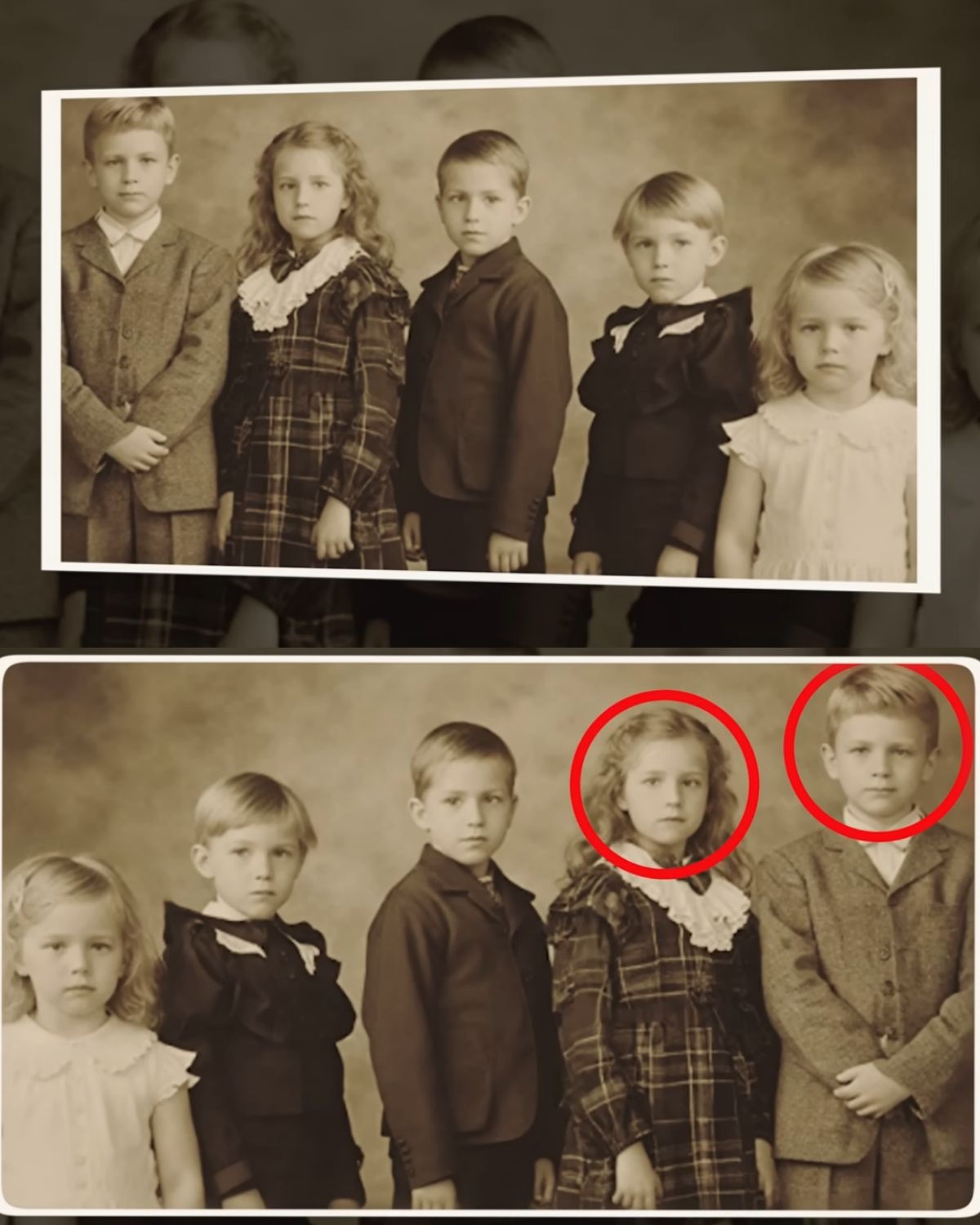

At a glance, the photograph seemed typical of its era: five children, dressed formally, standing rigidly side by side. Unsmiling, as was customary for long-exposure photography.

But something about it made Evelyn pause.

Beneath the image, written in thin, looping ink, were the words:

“Lambeth, 1901. Five children.”

And yet, as she studied the faces more carefully, one detail felt… off.

—

The smallest child, a girl no older than three, stood at the far left. Unlike the others, her head tilted slightly. Her eyes were closed.

While the other children faced the camera directly, her posture seemed unusually rigid — almost supported rather than natural. Her arms hung stiffly at her sides. The lighting, too, felt deliberate: soft illumination on the children, with a dark, indistinct background behind them.

Evelyn was familiar with memorial photography. During the Victorian period, it was common for families to commission images of loved ones shortly after their passing, posed peacefully and surrounded by relatives.

She had studied dozens of such examples.

But this one felt different.

Not because it depicted loss — but because of how carefully controlled the scene appeared.

—

To preserve the photograph, Evelyn submitted it for high-resolution digital scanning. What the lab returned would change the entire interpretation of the image.

The enhanced scan revealed subtle details invisible to the naked eye. The youngest girl’s dress appeared slightly oversized, as though borrowed. Her shoes did not match. And beneath her wrist, barely visible, was the faint outline of a thin metal support — the kind used in early photography to stabilize subjects during long exposures.

It became evident that the smallest child was not standing independently at the time the photo was taken.

This suggested the image was a form of post-event portraiture — not uncommon for the era.

But questions remained.

—

Why had the family chosen to photograph the children outdoors, at night, without the traditional mourning arrangements common to such images? Why no flowers, no drapery, no visual cues of remembrance?

Evelyn began researching the family name and location listed beneath the photograph.

Census records from 1901 showed a household in Lambeth matching the description: Edwin and Lillian Langford, living with five children — James, Mary, George, Peter, and Clara.

Further records revealed that Clara Langford had been registered in burial documents dated March 6th, 1901, with illness cited as the cause.

The photograph, according to a faded studio marking, had been taken on March 5th.

Just one day earlier.

—

This meant the photograph was not taken as a remembrance after burial. It was created during a narrow window of time before official records were finalized.

Evelyn contacted Dr. Hugh Calder, a forensic historian specializing in early photographic analysis. After reviewing the scan, his observations were immediate.

“This is a deliberately arranged composition,” he explained. “Notice how the other children subtly angle away from her. No one is touching her. Their hands are hidden or stiffly placed.”

He pointed out their expressions.

“This isn’t just formal posture. It suggests discomfort.”

—

In many Victorian memorial images, the departed was often held or closely embraced by family members. Here, the separation was clear.

The setting also raised concerns. Why had the session been rushed? Why conducted privately, away from a studio?

Evelyn searched trade directories and uncovered a short-lived photography service operating in Lambeth around that time:

E. Chilturn & Sons, specializing in private commemorative photography.

The name appeared once more — in a 1902 court ledger related to an irregular licensing complaint. The allegation mentioned “misrepresented photographic documentation,” though no formal charges followed.

The trail grew colder — until Evelyn examined the donation records from the Ketley estate more closely.

—

Among Dr. Ketley’s medical ledgers was a handwritten entry dated March 4th, 1901:

“Langford household visit.

Clara L., age 3. High fever. Condition worsening. Family informed. Certification pending.”

Beneath it, another note appeared:

“Private image arranged prior to documentation.”

This wasn’t merely a family keepsake.

It was a delay.

—

Why would a family postpone formal records long enough to stage a photograph?

The answer emerged through probate archives.

Just weeks later, an inheritance from Edwin Langford’s estranged father had been distributed. The terms were clear: funds were to be divided equally among Edwin’s living children at the time of execution.

If any child was no longer alive, that portion would be redirected to the executor.

The photograph, dated precisely one day before the estate’s release, may have served as informal proof that all five children were present.

—

In an era when documentation moved slowly, visual evidence could carry weight — especially when no one questioned it.

The photograph suddenly took on a new meaning.

It explained the rushed timing. The private setting. The involvement of a physician. The unusual restraint of the children.

They were not grieving.

They were following instructions.

—

One final detail emerged during a later enhancement.

Inside the youngest girl’s sleeve, a small fabric tag bore stitched initials: “C.K.”

Not “C.L.”

Clara Langford’s initials should have been “C.L.”

Evelyn returned to Ketley’s earlier records and found another entry:

“Clara K., age 4. Respiratory decline. Prognosis poor. Mother: Margaret. Unmarried.”

No burial record followed.

It appeared this child had quietly disappeared from official documentation.

—

The implications were chilling.

The girl in the photograph may not have been Clara Langford at all — but another child, used to create the appearance of continuity at a critical legal moment.

A single image. A single date. A carefully orchestrated illusion.

—

Evelyn documented her findings cautiously, framing them as evidence of historical manipulation rather than accusation.

When her research was published in the Journal of Victorian Material Culture, it sparked widespread discussion about grief, desperation, and the ethical gray zones of the past.

Evelyn declined interviews.

In her personal notes, she wrote:

“The question is not who deceived whom — but how circumstance, loss, and survival shaped decisions in an era with few safeguards.”

—

The photograph remains archived today — no longer viewed as a simple family portrait, but as a reminder of how much meaning can hide within a single image.

Sometimes, history doesn’t shock us because of cruelty.

But because of how quietly people adapt when faced with impossible choices.