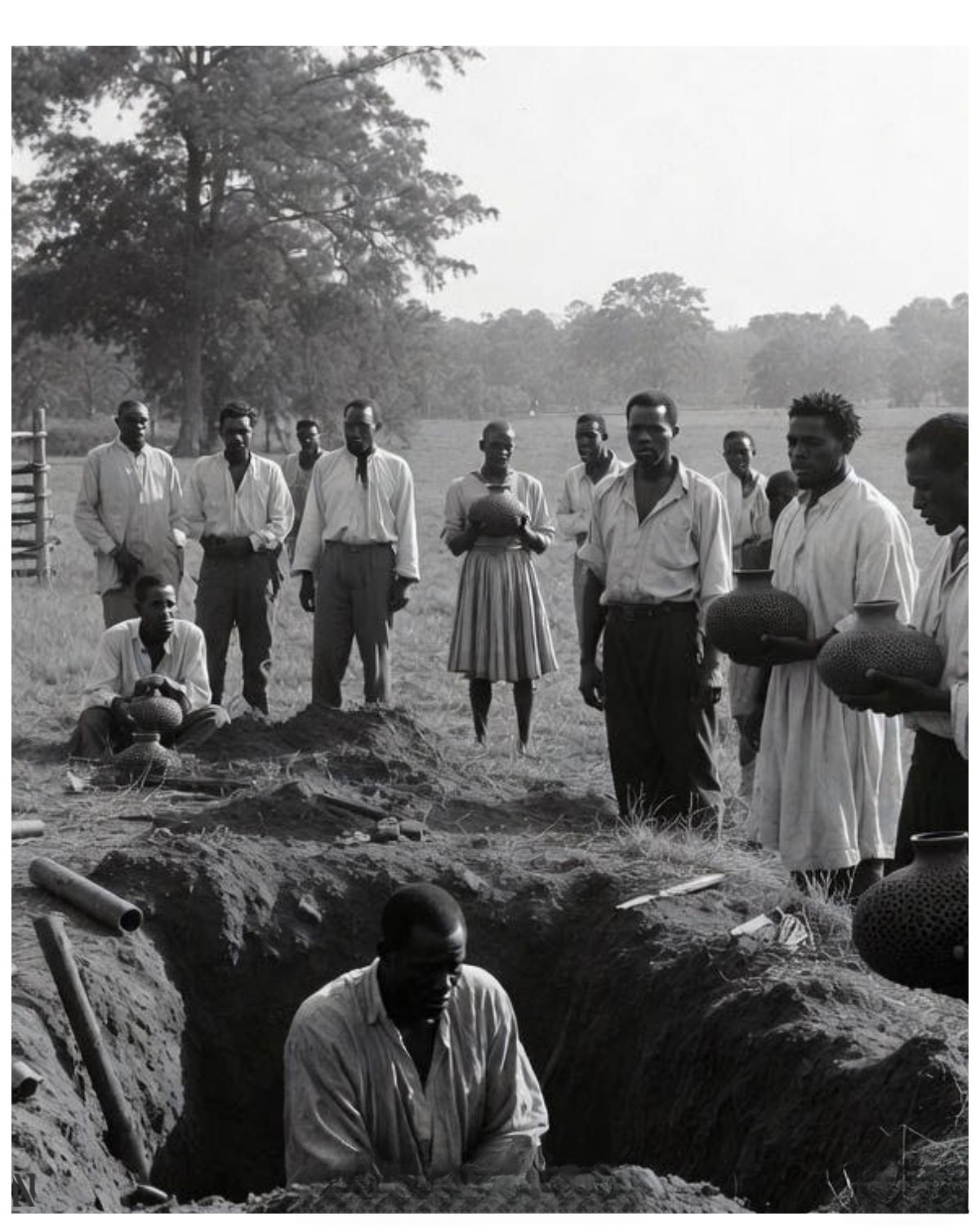

Alabama and Georgia Plantations, 1839: The Rituals History Chose Not to Record

The year was 1839.

Across Georgia and Alabama, vast plantations operated as closed worlds—self-contained systems governed not only by crops and labor, but by law, custom, and fear. These estates were not simply agricultural enterprises. They were structures of absolute authority, where wealth and social rank granted unchecked control over every aspect of life within their borders.

From the outside, plantations projected order.

White columns framed large houses. Churches were attended. Guests were hosted. Plantation families were praised for refinement and moral standing. To neighboring communities, these estates appeared stable, even admirable.

But plantations were places where public image and private reality rarely aligned.

Within their boundaries, enslaved people lived under constant surveillance, subject to rules that extended far beyond labor. Every movement, every word, every refusal carried consequences. The law did not recognize them as witnesses or victims. Harm done to them was measured not in human terms, but as property loss.

This legal erasure created an environment where abuse did not need secrecy. Silence was already enforced.

Power Without Accountability

In 1839, Southern law granted plantation households near-total authority. Enslaved men and women could not testify against white individuals. Courts protected ownership, not humanity. This single legal fact shaped everything that followed.

What occurred behind plantation gates was treated as private domain, shielded from scrutiny. Neighbors did not ask. Courts did not intervene. Churches preached obedience. Respectability became armor.

Within this system, patterns emerged—repeated routines that enslaved communities recognized but could never openly challenge. These were not isolated acts, but structured practices sustained by power, predictability, and the certainty of impunity.

Among the enslaved, such patterns were remembered not because they were announced, but because power leaves traces. Certain people were summoned. Certain spaces became dangerous. Certain times were avoided. Fear developed its own geography.

These practices endured not because they were rare, but because the system was designed to keep them invisible.

Silence as a Mechanism

Silence was not accidental. It was engineered.

Plantation life demanded restraint. Survival required knowing when not to speak, where not to stand, what not to notice. Children learned early which paths to avoid and which questions were dangerous.

Stories moved quietly through the quarters in fragments—warnings rather than accusations. Names were omitted. Details softened. Memory was preserved not for justice, but for survival.

This is why so many plantation abuses were never recorded in official archives. Records favored ledgers, architecture, and yields. Diaries spoke of hospitality. Letters avoided disruption. Even later historical accounts often relied on documents written by enslavers, unintentionally reproducing the same silences.

What survived instead were patterns.

A System, Not an Anomaly

What makes these histories unsettling is not their uniqueness, but their consistency.

Across Georgia and Alabama plantations, post-emancipation recollections, abolitionist hints, and oral histories reveal similar structures: authority without oversight, silence enforced by law, and abuse normalized through power.

These patterns are not unique to the American South. Scholars studying colonial systems elsewhere—including indigenous communities under European rule—have identified comparable dynamics. Different cultures, different laws, but the same logic: when absolute control exists without accountability, exploitation follows.

The plantation was not merely a workplace. It was a closed moral universe where hierarchy replaced ethics.

Survival as Intelligence

Despite this environment, enslaved communities were not passive.

Survival required intelligence, observation, and cooperation. Knowledge became currency. Elders taught the young which overseers were dangerous, which moments offered brief safety, and how to disappear into routine when necessary.

Resistance often took subtle forms. Tasks completed imperfectly. Tools misused. Information shared quietly. Cultural practices preserved in song, prayer, and story. These were not open rebellions, but assertions of humanity within a system designed to erase it.

Music carried layered meanings. Stories encoded lessons. Humor provided momentary relief. Family bonds became protective structures.

Psychological resilience was not optional. It was required.

The Cost of Endurance

The emotional toll of this constant vigilance was immense.

Trauma did not end with the individual. It shaped families, behaviors, and memory across generations. Silence became both shield and wound—necessary for survival, but costly in the long term.

After emancipation, many former enslaved people remained cautious about speaking openly. Power structures had shifted, but fear persisted. Communities learned that memory itself could be dangerous.

As a result, many truths survived only in fragments. Stories without names. Warnings without explanations. Behaviors shaped by histories never fully spoken.

This absence has often been misinterpreted as lack of evidence. In reality, it is evidence of how thoroughly silence was enforced.

Why These Stories Matter

Confronting this history is not about sensationalism. It is about accuracy.

Slavery’s brutality was not limited to chains and forced labor. It operated through legal structures, social norms, and psychological domination. Abuse thrived not in chaos, but in order—protected by law and masked by respectability.

Understanding this requires moving beyond romanticized plantation imagery and sanitized historical narratives. It requires listening to what was whispered, not only what was written.

The plantation households of 1839 were not aberrations. They were products of a system that rewarded control and erased accountability.

Memory Against Erasure

Even today, the echoes of these structures remain.

Communities descended from the enslaved carry inherited caution, resilience, and cultural memory. The strategies developed under bondage—adaptation, solidarity, coded communication—did not disappear. They evolved.

History, when told honestly, must account for both oppression and endurance.

The rituals history tried to erase were not simply acts committed in secrecy. They were sustained by silence, legality, and social consent. Breaking that silence now is not about revisiting horror, but about refusing erasure.

What haunted Georgia and Alabama in 1839 was not one household or one individual. It was a system.

And systems leave legacies.

Recognizing that truth does not diminish history. It completes it.