The silence in Covington County, Mississippi, could fool people who didn’t know how the heat held memories. On a still night, the fields looked calm from a distance. The big house stood bright against the dark, confident in its columns and its rules. The quarters lay farther back, half-hidden in pine and shadow, where whole lives unfolded without being recorded.

In September of 1859, that silence cracked—not with thunder, not with war drums, but with a kind of panic that moved through the plantation like smoke. It began as sound, sharp and sudden, from different corners of the Thornhill estate. Not the kind of shouting that comes from a bar fight or a hunting accident. The sound of men realizing the world they controlled could not protect them from consequence.

At the center of the whispers that followed was a woman named Esther.

For seventeen years, the white families around Natchez and beyond had treated Esther like a rare advantage—an enslaved midwife whose hands seemed to “just know” what to do. They spoke of her like a miracle they owned. They borrowed her as if she were equipment. They praised her skill in the same breath they denied her personhood.

Esther brought babies into the world. She calmed frightened mothers. She carried a worn medical bag and a calm face that made rooms settle. She was invited into the most private moments of powerful households, trusted with their fear, their shame, their prayers. When an outcome was good, the credit went to Providence, to the master’s good fortune, to the doctor’s supervision. When an outcome was hard, the blame fell anywhere it could—never on the system itself.

In the plantation ledger, Esther had a price.

In the world inside her, she had a name that came first, long before Mississippi tried to rename her. Older women in her family had carried knowledge like a living inheritance: which plants could ease pain, which ones could slow bleeding, which ones could calm a fever, which rituals helped people breathe through terror. Esther’s skill did not come from the plantation. It came with her, carried through loss, protected by silence.

She learned fast that skill could keep you alive—but it could also make you a target.

A talented enslaved person was not treated like a human being with gifts. They were treated like a more valuable possession. A “special” person was still owned. Sometimes that meant better food, cleaner clothes, a different sleeping place. Sometimes it meant being pulled closer to the very people you most needed distance from.

Esther lived inside that contradiction for years.

By day she moved through polite rooms, listening to white women speak softly of faith while the system outside their windows swallowed families whole. By night she returned to the quarters, where the truth was spoken in fragments—carefully, because the wrong words could travel.

And in the middle of all that, Esther built the only thing that ever felt like it belonged to her.

A family.

She found steadiness with Samuel, the blacksmith, a man whose strength wasn’t loud. Their marriage had no legal protection. Their future had no guarantee. Still, in a world that kept trying to turn people into tools, they made a home out of what they could: shared food, shared silence, shared plans whispered after dark.

In 1852, their daughter Grace was born.

Grace became the center of Esther’s endurance. She was bright-eyed, curious, quick to notice what others missed. Esther tried to teach her the first rule of survival on a plantation: be careful where you stand, who you look at, what you say. She taught her to stay close to safe adults and far from the big house. She taught her to move quietly. She taught her, gently, that some parts of the world were dangerous not because of storms or snakes, but because of people.

At night, Esther whispered old plant names like lullabies. Not to make Grace a doctor at seven years old, but to give her something the system could not steal: a sense that she came from more than fear.

For a long time, Esther’s reputation offered a thin layer of protection. Her cabin—small, plain, and still under surveillance—was treated as a “medical space,” as if calling it that made it hers. The white families wanted her steady hands available, so they did not want her visibly broken. That was the limit of their restraint.

The protection did not extend to dignity.

The protection did not extend to safety.

The protection did not extend to Grace.

In late summer of 1859, the harvest pressure rose. Workdays stretched. Tempers shortened. The plantation’s rules grew sharper at the edges. Small “protections” that existed on calmer weeks began to fray. Esther was called away for a difficult delivery on another estate, gone longer than planned, leaving Grace in the medical cabin under the watch of people who were distracted, exhausted, and careless.

What happened during Esther’s absence was not recorded in any official book. The plantation did not keep accounts of harms that would force it to face itself. But when Esther returned, the air felt wrong. People avoided her eyes. A hush sat over the quarters the way it does after a community has been wounded.

Esther found Grace surrounded by women who were doing everything they could—comforting, cooling, praying, holding. Samuel stood nearby like a man trying not to fall apart. No one needed to explain in full. Esther could read a room the way other people read letters.

Her daughter’s light was fading.

Grace stayed awake long enough to recognize her mother’s voice, long enough to reach for her hand. Esther held her, steady and close, and promised her the only promise she could make in that moment: that she would not forget.

When Grace died, something in Esther went quiet in a new way.

Not numb.

Not empty.

Focused.

People often expect grief to look like noise. Esther’s grief looked like a still surface over deep water. She did not turn into a screaming ghost. She turned into a woman who understood the truth of her world with a clarity that left no room for bargaining.

She also understood something else: Mississippi would not give her justice.

In the eyes of the plantation order, the suffering of an enslaved child was not a crime the way the suffering of a white child was. It was a problem to be managed, a liability to be hidden, a threat to the plantation’s reputation—nothing more.

If there was going to be an accounting, it would not come from the courts.

And Esther knew she could not simply “fight” her way through a system built to crush resistance. Brute force was not her advantage. Loud revenge would not end with justice; it would end with her death and more punishment for the people she loved.

So Esther did what she had always done to survive.

She observed.

She planned.

She disappeared.

In the days after Grace’s burial, Esther moved like a woman carrying ordinary sorrow. She treated the sick. She kept her voice low. She did not announce anything. The plantation’s inner circle—men who believed control was their birthright—remained confident in their routines. They did not imagine that the healer they paraded like a trophy had a mind built for strategy.

Then, one night, the plantation woke up to fear.

Not fear of fire. Not fear of an uprising in the fields. A different fear—more personal, more humiliating. The fear that someone inside the system had reached a breaking point and had found a way to make the powerful feel vulnerable without ever facing them in open daylight.

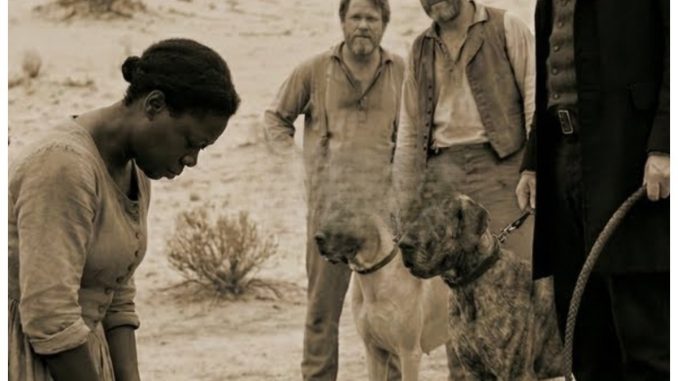

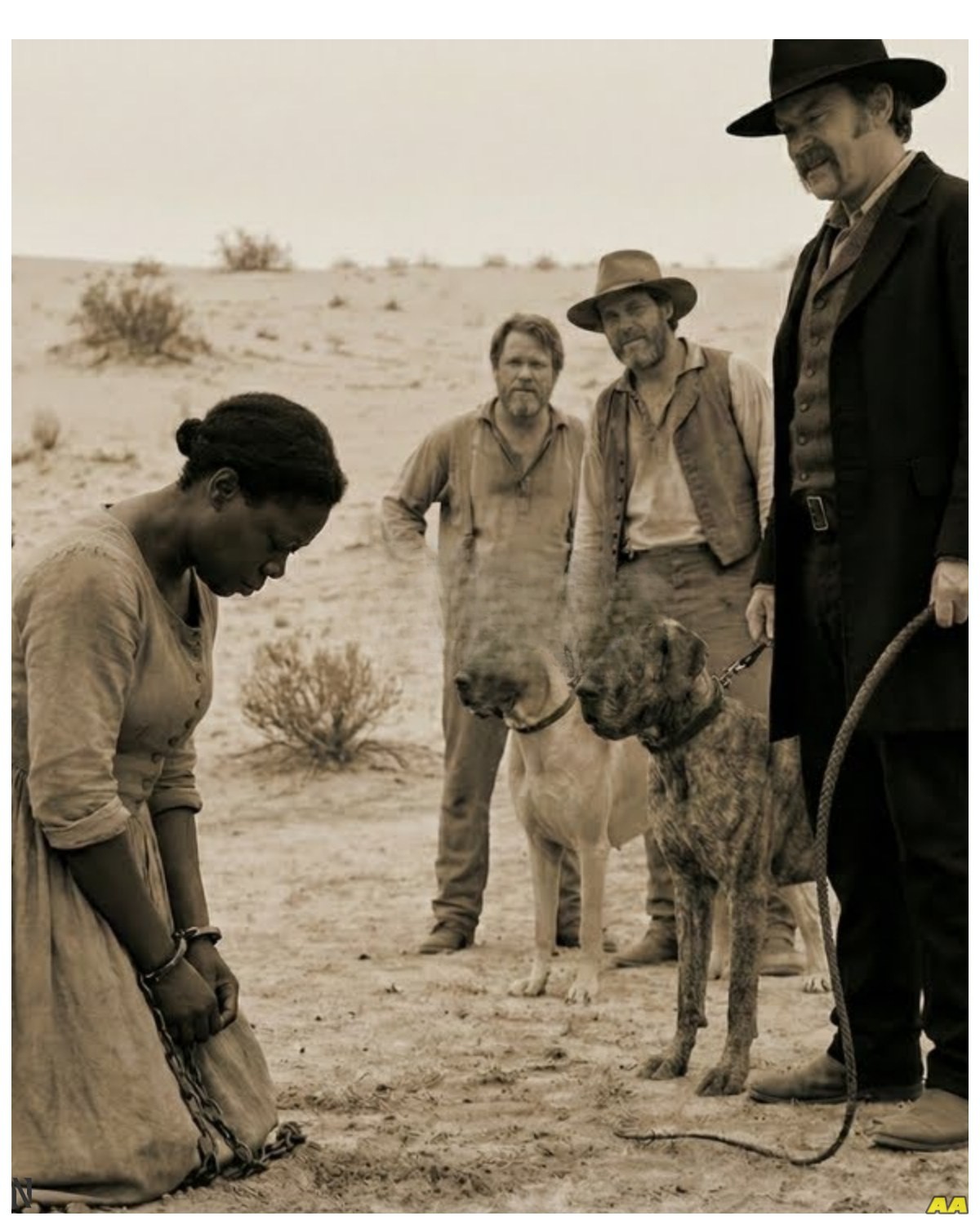

By dawn, word had spread through the estate: something had happened to the men who ran Thornhill, something that stripped them of swagger, something that made them retreat into locked rooms and tight voices. The plantation tried to control the story, but panic has its own mouth. Riders were sent out. Dogs were loosed. Neighbors were called. The search began with a violence the system knew well.

But Esther was no longer there.

She had left no farewell. No confession. No dramatic last words. She left the way people who have spent a lifetime learning how to survive leave: quietly, with prepared supplies, with memorized routes, with help from a network that existed precisely because the law refused to protect them.

In the weeks that followed, Thornhill Plantation became a place of suspicion. Overseers watched one another. The doctor blamed the staff. The colonel blamed the night. Everyone blamed “outside agitators” because admitting the truth was unbearable: that an enslaved woman, once treated as background, could outthink them.

In the quarters, people spoke in whispers. Not the kind of whispers that celebrate harm. The kind that acknowledge a shift in power. The kind that remind a community that the system’s confidence was not the same thing as invincibility.

Esther’s name became a rumor carried carefully. Some said she made it north. Others said she crossed into a free Black community and took another name. Some claimed she lived near a lake city and helped families through sickness and childbirth, quietly rebuilding what the plantation tried to destroy.

No official record confirms it. Plantations were excellent at keeping books about cotton and money, and terrible at recording the humanity of the people they exploited.

But the story survived anyway, as family stories do.

Not as a manual for revenge.

As a warning about what happens when a society builds comfort on cruelty and then pretends surprise when the cruelty echoes back.

If Esther truly vanished into freedom, she did not do it as a mythic warrior. She did it as what she had always been: an expert at life, a student of survival, a woman who refused to let the system write the last line of her story.

And in that refusal, the plantation learned something it never wanted to learn.

The most dangerous person in a place built on dehumanization is not always the strongest.

Sometimes it’s the one who has been forced to stay quiet long enough to become precise.