In September 1802, a newspaper in Richmond, Virginia, printed a story that stunned the young American nation. It claimed that the sitting President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson—the man who had written the words “All men are created equal”—had maintained a long, private relationship with an enslaved woman named Sally and had fathered several children with her.

The revelation surfaced in the middle of Jefferson’s presidency. His political opponents seized on it immediately, using the story as a weapon. Newspapers circulated mocking cartoons. Church sermons condemned him as a moral contradiction. Yet Jefferson himself offered no response. He neither denied nor confirmed the accusation. He remained silent, and that silence endured for nearly two centuries.

What the article did not fully explain was even more unsettling. Sally Hemings was not only enslaved by Jefferson; she was also the half-sister of his late wife. The two women shared the same father. When Jefferson’s wife died, he inherited Sally. She was nine years old. Years later, Sally would give birth to six children, all fathered by the same man.

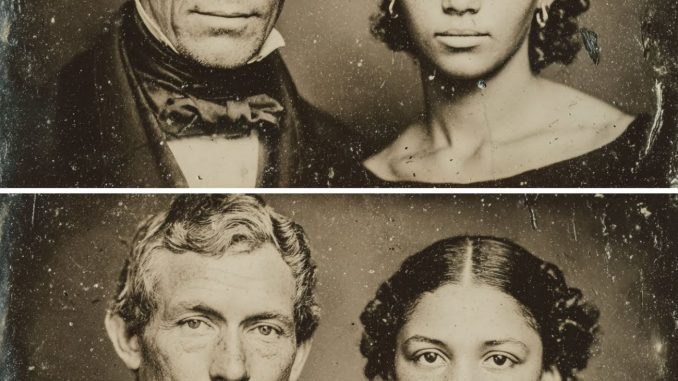

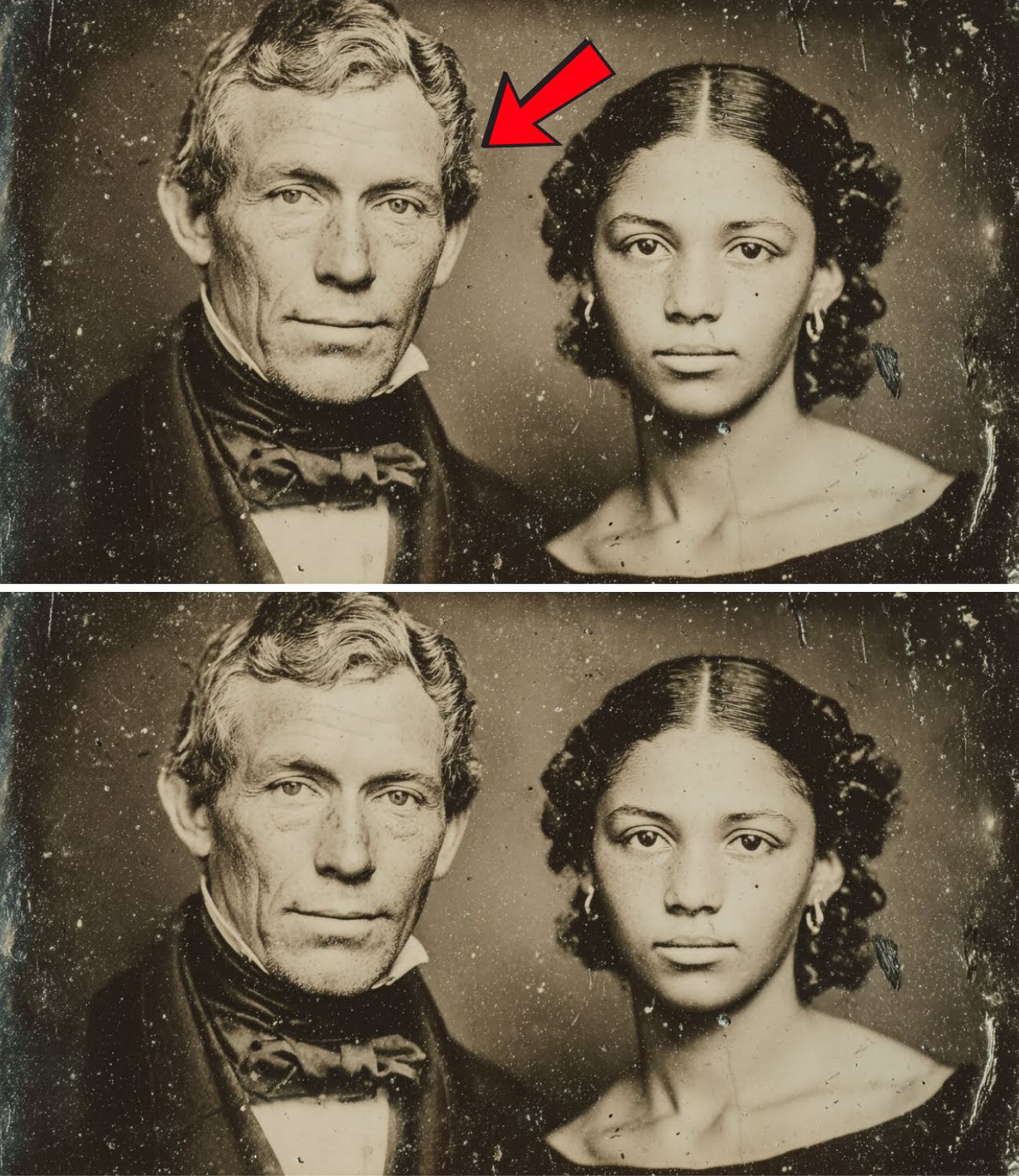

All of those children were born into slavery. All had skin light enough to blend into white society. All carried Jefferson’s features. The author of the Declaration of Independence lived with a hidden family formed with his deceased wife’s sister.

How did a teenager become involved with the most powerful man in the country? Why did Sally return from Paris when she could have remained legally free? And how did this arrangement continue under one roof for decades without intervention? To understand, the story must begin years earlier, in 1787, when Thomas Jefferson brought Sally Hemings with him to France.

This is the history America avoided confronting for generations. A story whispered, denied, and eventually confirmed only through science. It begins in Virginia.

In 1782, Thomas Jefferson was 39 years old. He was a lawyer, a statesman, an architect, and a philosopher. Six years earlier, he had written the Declaration of Independence. He owned a large plantation called Monticello, where hundreds of enslaved people lived and worked. He was widely admired as a man of ideas and principles.

That same year, tragedy struck. His wife, Martha, died shortly after giving birth to their sixth child. Jefferson was devastated. He withdrew from public life for weeks. When he emerged, he made a vow: he would never remarry. He kept that promise, but found another way to fill the absence.

Martha had brought land, wealth, and enslaved people into the marriage, including the Hemings family. Their matriarch, Elizabeth Hemings, had twelve children. Six were fathered by John Wales—Martha’s father. One of those children was Sally.

Sally Hemings was nine years old when Martha died. She was light-skinned, with straight hair and delicate features. Her father was the same man who had fathered Jefferson’s wife. That made Sally Martha’s half-sister—and Jefferson’s legal property.

Unlike most enslaved children, Sally was not sent to the fields. She worked inside the main house, assisting with domestic tasks, staying close to Jefferson’s family. This arrangement was unusual, but the Hemings children occupied a unique position due to their family ties.

Time passed. Jefferson entered public service as Governor of Virginia and later as a diplomat. In 1784, he traveled to France, taking his eldest daughter with him. Three years later, he arranged for his younger daughter, Polly, to join him. When the ship reached Europe, the child was accompanied not by an adult woman, but by 14-year-old Sally Hemings.

Jefferson accepted the change without protest. Sally arrived in Paris in the summer of 1787. For the first time, she experienced a world where slavery was not legally recognized. She lived in Jefferson’s household, learned French, refined domestic skills, and moved freely in public spaces. Technically, she was not enslaved under French law.

She could have stayed. She could have sought freedom. But she was young, isolated, without resources or support beyond the Jefferson household. Jefferson observed her closely during those years—her resemblance to his late wife, her growing confidence, her presence in his home.

At some point during their time in France, Jefferson and Sally began an intimate relationship. He was in his mid-forties. She was a teenager. The imbalance between them was absolute—age, status, power, and authority all on one side.

In 1789, Jefferson prepared to return to the United States after being appointed Secretary of State. Sally resisted. According to later testimony from her son, she wanted to remain in France, where her child—she was pregnant—would be born free. Jefferson could not legally compel her to return.

Instead, he negotiated. He promised her special treatment if she came back to Virginia. Most importantly, he promised that her children would be freed when they reached adulthood. Faced with limited options, Sally agreed.

She returned to Monticello pregnant. Her first child did not survive infancy. Over the next two decades, she would give birth five more times. Four of those children lived to adulthood.

During these years, Jefferson rose to the highest office in the land. He served as Vice President and then as President. He divided his time between Washington and Monticello. Each time he returned, Sally remained nearby, living in a room adjacent to his own.

The children grew up at Monticello. They were not assigned to the fields. They learned trades, received better treatment, and gradually gained quiet freedoms denied to others. Their resemblance to Jefferson was widely noted, but rarely spoken aloud.

In 1802, journalist James Callender published the accusation that brought the secret into public view. The backlash was immediate. Jefferson’s opponents attacked him relentlessly. Yet Jefferson maintained silence, and the controversy faded.

Life continued much as before. Sally gave birth to her final child in 1808. Jefferson completed two terms as president and retired to Monticello in 1809. Sally remained enslaved.

When Jefferson died in 1826, he freed only a handful of enslaved people in his will. Among them were three of Sally’s children. Sally herself was not formally freed. She left Monticello shortly afterward with her children and lived quietly in Charlottesville.

Her children took different paths. Some passed into white society, concealing their origins. One, Madison Hemings, lived openly as a Black man and later told the full story in a newspaper interview. For decades, his account was dismissed.

Jefferson’s descendants denied the story. Historians minimized it. The nation preferred a simpler narrative.

In 1998, DNA evidence confirmed the connection between Jefferson’s lineage and Sally Hemings’ descendants. Science verified what had long been whispered.

Today, the story is acknowledged openly. Monticello includes Sally Hemings in its history. But recognition came long after her death.

Thomas Jefferson remains celebrated as a Founding Father. Sally Hemings lived and died without public acknowledgment. Their story reveals the contradictions at the heart of American history—a tale of power and silence, ideals and reality, remembered only when the evidence could no longer be ignored.