By any honest moral standard, the slave patrols of the American South were never true guardians of order. They were instruments of fear, empowered by law to stop, question, punish, and destroy Black lives with little scrutiny and no consequence. Their authority was designed to move in one direction only, flowing from white riders to enslaved bodies. In the late 1850s, in the heart of Alabama’s Black Belt, one woman decided that fear would no longer travel so easily.

Her name was Priscilla Green.

For nearly two decades, she lived as an enslaved hunter and tracker on the Whitmore Plantation in Sumter County. Each morning, she entered the forests and swamps to provide food for the household, moving quietly through pine corridors and river bottoms, learning the land not as scenery but as language. Every footprint told a story. Every change in soil or water revealed intention. Survival required attention, and attention became knowledge.

She also carried something older than America, something passed down through women in her family long before chains or plantations existed. It was not a weapon in the usual sense. It was understanding—of terrain, of human habit, of how the natural world could protect or destroy depending on how it was approached.

For years, that knowledge remained dormant. Silence was safety. Obedience was survival.

Then, in May of 1859, Priscilla’s fourteen-year-old daughter, Mercy, was stopped on a dirt road by a slave patrol. She carried a written pass, but written permission meant nothing when belief itself was denied. The men accused her of deception. Witnesses were ignored. By nightfall, Mercy was dead, killed publicly, her body left hanging as a warning.

For three days, Priscilla was forced to pass that place. To see. To endure. To remain silent.

She buried her child without ceremony, without protest, without visible grief. Those who knew her noticed something unsettling in that restraint. She did not collapse. She did not plead. She observed. Faces. Voices. Paths. Patterns.

Grief did not break her. It sharpened her.

In the months that followed, Priscilla continued her daily routines. She hunted. She cooked. She moved in and out of the plantation as she always had. To those who owned her, nothing appeared different. That invisibility—so long a condition of her existence—became her protection.

But beneath that quiet surface, she began to study something new.

The patrols.

Men on horseback believe themselves powerful. Power breeds predictability. Riders favored the same trails, the same crossings, the same clear paths through the forest. They traveled in formation. They paused in familiar clearings. They trusted the ground because it had never betrayed them before.

Priscilla noticed everything.

She learned when they rode and where they turned back. She learned how rain changed the earth and how dry spells hardened it. She learned where horses hesitated and where they rushed forward. She learned that fearlessness often masquerades as confidence—and that confidence dulls attention.

By late autumn of 1859, something changed in Sumter County.

Patrols began to vanish.

At first, the disappearances were explained away. A rider drowned. A horse fell. A man failed to return. But the incidents accumulated. Entire groups entered familiar stretches of forest and did not emerge. Bodies were found days later, sometimes far from where they were last seen, sometimes in places that defied easy explanation.

There were no uprisings. No crowds. No warning shots.

Only absence.

And then fear.

The white communities whispered about bad luck, sickness, treacherous land. Some blamed weather. Others spoke vaguely of old tricks or unseen dangers. Almost no one publicly entertained the idea that an enslaved woman—quiet, obedient, overlooked—could be responsible.

The thought itself was too destabilizing.

Yet among the enslaved, another understanding spread quietly. Someone was answering for Mercy.

Priscilla remained unseen. She passed through the big house daily, serving meals, carrying tools, returning from hunts. Her face revealed nothing. The same blindness that had allowed men to kill her child without consequence now shielded her from suspicion. To the patrols, she was labor. Background. Noise.

Not a mind.

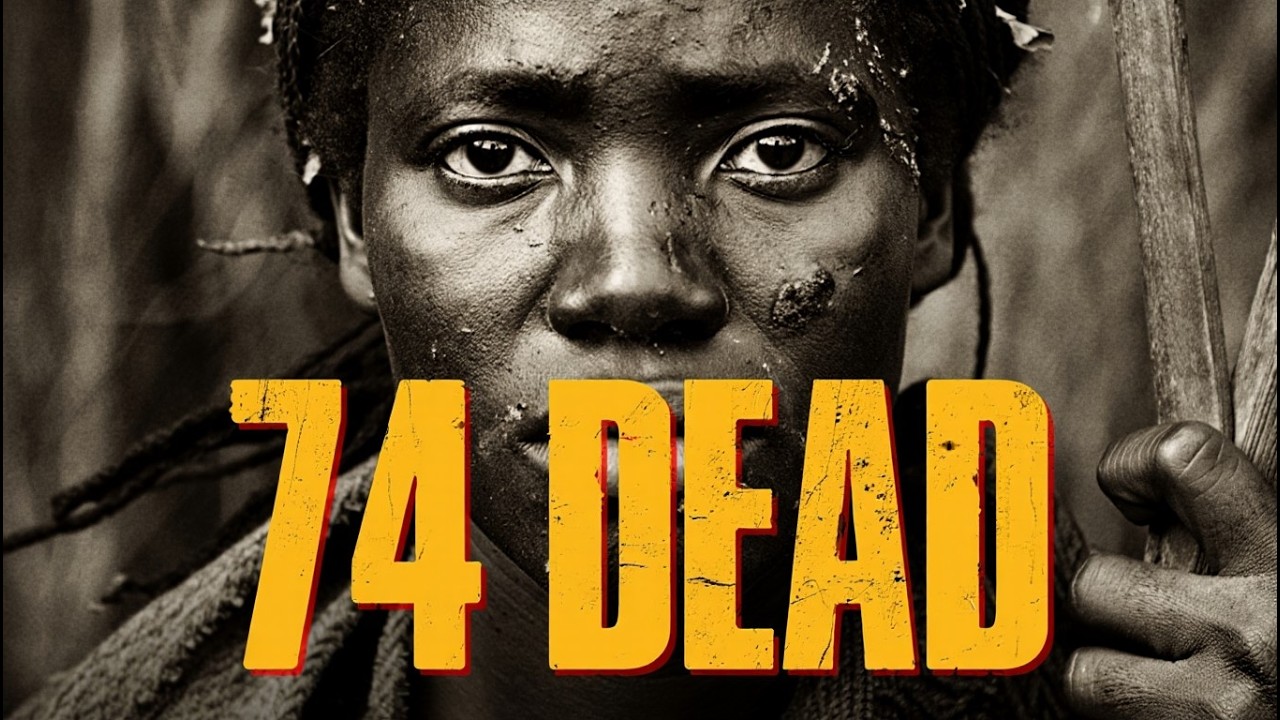

Between November and February, the deaths mounted. Seventy-four patrol riders would never return home. Wives pleaded. Mothers prayed. Men argued over who would ride first and who would bring up the rear. Patrol routes shifted. Torches were added. Dogs were brought. Still, the fear persisted.

The riders had lost something more important than numbers.

They had lost certainty.

For the first time, authority felt fragile. The forest—once merely a space to be controlled—became something else entirely. A place that did not answer to laws written in courthouses or enforced by whips. A place that did not recognize racial hierarchy.

Historians approach this story carefully, as they must. Enslaved resistance was rarely recorded honestly in official documents, and oral histories were often guarded for generations. Details blur. Timelines overlap. But across accounts, certain truths align: the killing of a child, a season of unexplained patrol deaths, widespread panic, and rumors of a woman who “knew the land like breath.”

None of this surprises those who understand slavery.

What unsettles is the scale—and the implication.

The slave system depended on a dangerous contradiction. It declared Black people inferior while relying completely on their expertise. Hunters, trackers, midwives, builders, river pilots—enslaved knowledge sustained the very world that denied their humanity.

Priscilla’s story exposes that contradiction.

She did not strike blindly. She did not seek chaos. She used understanding—of land, of habit, of arrogance—to interrupt a system that had left her no lawful path to justice. The men who killed her daughter would never face trial. The law would never acknowledge her loss. Her grief had nowhere sanctioned to go.

So it went elsewhere.

Violence, even when born of unimaginable injustice, carries consequences history cannot cleanly resolve. Among the dead were men who had laughed while enforcing cruelty. Others were participants in a system they lacked the courage to refuse. Their families mourned. Their absence rippled outward.

History offers no simple balance sheet.

What it does offer is context.

Priscilla did not act because she desired harm. She acted because the law had declared her child disposable. Because silence had failed. Because survival had taught her that knowledge, applied patiently, could become power.

By early 1860, the worst of the panic subsided. Patrols altered their behavior. Some men refused to ride at all. The deaths slowed, not because the threat disappeared, but because fear had reshaped movement.

The damage, however, was lasting.

For years afterward, white families spoke quietly of “the winter the forest took men.” Among the enslaved, a different memory endured. The understanding that the system was not invincible. That even in the deepest imbalance of power, resistance could take forms the law never anticipated.

What became of Priscilla Green is uncertain. Some say she disappeared into Union lines when war came. Others believe she fled north. Some insist she lived out her days quietly, never questioned, never named.

The record grows quiet where certainty is most desired.

But the meaning remains.

This is not a story of victory. Mercy did not return. The years stolen were not restored. And the end of slavery did not erase the structures of control it created.

It is a story of refusal.

Refusal to accept that grief must remain silent. Refusal to accept that intelligence belongs only to those in power. Refusal to accept that humanity can be erased by law.

The land remembers what people try to forget. And stories like this persist because they expose an uncomfortable truth: the enslaved were never passive. They were thinkers, observers, planners—living under extraordinary constraint, yet never without agency.

Priscilla Green did not bend history toward mercy. She bent it toward truth.

And in doing so, she forced a society built on terror to confront, however briefly, the consequences of believing some lives did not matter.