Stanley “Tookie” Williams remains one of the most discussed figures in the modern history of American criminal justice. His life story intersects with issues of urban violence, personal responsibility, rehabilitation, and the death penalty—topics that continue to divide public opinion decades later. The final 24 hours before his execution in December 2005 did not simply mark the end of a legal case. They reignited a national conversation about whether transformation inside prison should carry moral or legal weight when a death sentence has already been imposed.

This article presents a neutral, factual account of Williams’ final day, the circumstances surrounding his execution, and why his case continues to be referenced in debates about punishment and redemption.

From Early Life to National Notoriety

Stanley Tookie Williams was born in 1951 in New Orleans and later moved to Los Angeles as a child. His adolescence and early adulthood unfolded against a backdrop of poverty, racial segregation, and limited economic opportunity—conditions that shaped many American cities in the late 20th century.

In the early 1970s, Williams became associated with the founding of the Crips, a street gang that grew rapidly and later became linked to widespread violence across California and beyond. Over time, the gang’s expansion contributed to long-term social damage in many communities, an outcome that Williams himself would later publicly criticize.

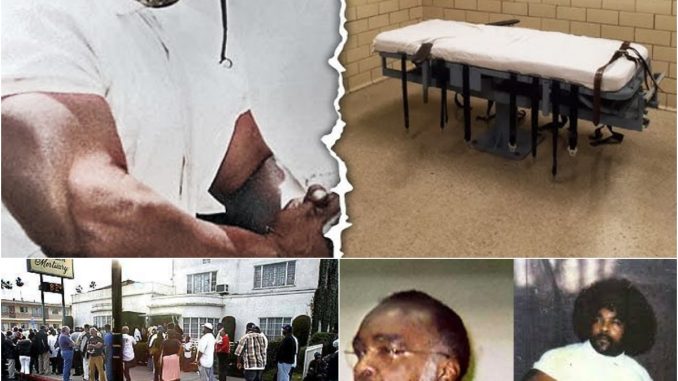

In 1979, Williams was convicted of four killings related to robbery incidents in Los Angeles County. He consistently maintained his innocence, but after years of appeals, his conviction and death sentence were upheld. He was sent to death row at San Quentin State Prison, where he would remain for more than two decades.

Life on Death Row and Claims of Transformation

During his incarceration, Williams’ public identity began to shift. He authored a series of children’s books and essays aimed at discouraging young people from joining gangs and engaging in violence. These writings were widely circulated and used in some educational and intervention programs.

Supporters pointed to this work as evidence of personal change. Over time, his advocacy efforts led to several nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize, a fact frequently cited by those who believed his sentence should be reconsidered. Critics, however, argued that awards and public recognition did not negate the seriousness of the crimes for which he was convicted.

This divide—between those who emphasized accountability for past actions and those who focused on demonstrated change—became central to the public debate surrounding his execution.

Clemency Requests and the Final Decision

As Williams’ execution date approached, supporters from various backgrounds urged California officials to grant clemency. The requests did not challenge the jury’s verdict directly but instead appealed to the governor’s authority to consider mercy based on post-conviction conduct.

At the time, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger reviewed Williams’ case and ultimately denied clemency. In his decision, the governor cited the absence of a clear admission of responsibility and questioned whether Williams had fully accepted accountability for the crimes.

The denial effectively exhausted Williams’ remaining options, setting the stage for the final hours of his life.

The Final 24 Hours at San Quentin

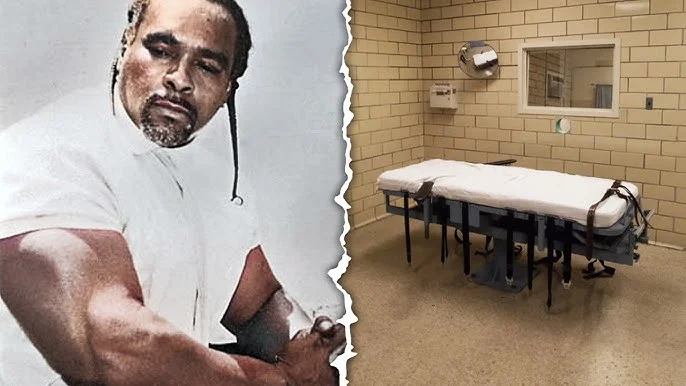

Williams was transferred to a closely monitored area of San Quentin State Prison as his execution date neared. Reports from witnesses and officials described him as composed and outwardly calm during this period.

On December 12, 2005, the day before the execution, Williams declined a traditional last meal. Instead, he chose a simple serving of oatmeal and milk, a decision that later became symbolic for supporters who viewed it as a sign of quiet acceptance rather than protest.

Throughout the day, Williams received approved visits from supporters and long-time acquaintances. Among them was his co-author and advocate, Barbara Becnel, who would later read his final statement publicly. Williams did not request extensive religious services, reportedly focusing instead on personal reflection.

Outside the prison, demonstrations gathered. Some protesters opposed the death penalty in principle, while others focused specifically on Williams’ case and the broader issue of rehabilitation.

The Execution Procedure

In the early hours of December 13, 2005, Williams was taken into the execution chamber at San Quentin. Witnesses included members of the media, prison officials, and representatives connected to the victims’ families.

The state carried out the execution by lethal injection in accordance with California law at the time. Williams did not deliver a spoken final statement in the chamber. His previously prepared message, later read by Becnel, emphasized his belief in personal change and his opposition to gang violence.

He was pronounced dead shortly after midnight. The execution marked California’s first use of capital punishment in several years and immediately drew national and international attention.

Public Reaction and Immediate Aftermath

News of Williams’ execution spread quickly. Supporters expressed disappointment and renewed criticism of capital punishment, arguing that the state had ignored evidence of rehabilitation. Opponents countered that the justice system had followed due process and that the sentence reflected the severity of the crimes.

Media coverage highlighted both perspectives, often framing the case as a test of whether transformation inside prison should influence final punishment. The attention extended beyond the United States, with international outlets examining the broader implications for human rights and criminal justice policy.

Why the Case Still Matters

Williams’ execution did not end the debate surrounding his life. Instead, it solidified his case as a reference point in ongoing discussions about the purpose of incarceration and the ethics of capital punishment.

Several unresolved questions continue to surface whenever his name is mentioned:

- Should evidence of positive change alter the outcome of a legally upheld sentence?

- Is remorse a necessary condition for mercy, or can impact alone justify reconsideration?

- What message does execution send about society’s belief in rehabilitation?

There is no consensus. For some, Williams’ case underscores the importance of finality and accountability. For others, it highlights what they see as a system unwilling to acknowledge transformation once a sentence is imposed.

A Broader Reflection on Punishment and Change

Viewed through a broader lens, the story of Stanley “Tookie” Williams illustrates the tension between justice as punishment and justice as prevention. His later work aimed at discouraging youth violence suggests that change can occur even in the most restrictive environments. At the same time, the legal system’s decision to proceed with execution reflects the weight given to original convictions and the rights of victims.

Today, Williams’ name appears frequently in academic discussions, policy debates, and educational settings—not as a symbol of innocence or guilt alone, but as a case study in how societies respond to claims of redemption.

Conclusion

The final 24 hours of Stanley “Tookie” Williams were not defined solely by the procedures of an execution. They represented the closing moment of a life that had evolved from influence in street violence to public advocacy against it, at least in the eyes of his supporters.

Whether one views his execution as justice carried out or an opportunity lost, the questions raised by his case remain unresolved. As debates over capital punishment, prison reform, and rehabilitation continue, Williams’ story endures as a reminder that the line between accountability and mercy is one society has yet to draw clearly.

Sources

CBS News – Execution Chamber Ordeal (2005)

Los Angeles Times – Tookie Williams Is Executed (2005)

SFGate – Williams Executed: Last Hours (2005)

NBC News – Convicted Killer Williams Put to Death in California (2005)

NPR – The Execution of Stanley Tookie Williams (2005)

New York Times – Excerpts From an Interview With Stanley Tookie Williams (2005)