The Whitmore Plantation was never the largest in Louisiana, but people in the parish spoke about it as if size didn’t matter. What mattered was control. Aldrich Whitmore ran his land the way some men ran armies: with rules that did not bend, punishments that arrived quickly, and an expectation that everyone beneath him would learn to anticipate his moods before he ever raised his voice.

His eldest son, Edward, was raised to inherit that certainty. The land. The house. The authority to decide what happened to everyone who lived and worked under the Whitmore name. The younger son, William, moved through the same halls like a visitor who had wandered into the wrong life. He read too much, questioned too easily, and carried a kind of discomfort that wealth could not smooth over. And then there was Caroline, a cousin taken in by the family, polished and watchful, promised to Edward in a marriage designed to fuse property with property. In public, they called it a match. In private, it was a contract with a ring.

Those were the names Louisiana would remember when the estate finally cracked.

But Flower’s name did not travel the same way. In records she was not listed as a person at all, only a line: female, age uncertain, mute. People who never looked closely at her believed she had always been that way, a quiet figure in the garden, a shadow moving between rose bushes and kitchen doors. The truth was simpler and far more revealing.

She had not always been silent.

Her silence began when she was six years old, back when her name was Iris, back when her world was the cramped cabins behind the main house and a mother who taught her how to survive by taking up as little space as possible.

That summer night in 1845, heat lay over the quarters like wet cloth. Iris stepped outside because the air indoors felt too tight to breathe. At first she heard nothing but insects, then a voice carried through the dark—her mother’s voice, not singing, not laughing, but strained and urgent in a way that made a child’s skin go cold.

Iris followed the sound without understanding what she was running toward. She found herself near the main house, near a basement window, small enough to stand beneath without being seen. She looked through the glass and saw her mother on the stone floor, and saw two figures above her—Aldrich Whitmore and his son Edward, still young enough to be called a boy by some, but already old enough to know exactly what power meant on that plantation.

A child’s body wants to do one thing in a moment like that: make noise, pull adults out of sleep, force the world to stop. Iris opened her mouth and learned that fear can be faster than sound. Something in her shut down. She backed away, ran, hid, and waited for morning like it was a rescue that might not come.

When her mother shook her awake the next day, Iris tried to speak and found that her voice would not return. The plantation doctor offered a comfortable explanation for the Whitmores—something about nerves, about a fragile constitution, about a child’s “fit.” Dela, her mother, did not need a doctor to name what had happened. She saw it in her daughter’s wide eyes, in her rigid posture, in the way Iris flinched at certain footsteps on the porch boards.

Dela did not collapse. She did not scream. She did not beg. She did what enslaved women on plantations like Whitmore did when the world proved it had no mercy for them: she folded her pain into daily routine and let something harder grow beneath it. Patience. Calculation. A quiet, disciplined kind of fury.

Iris—who would eventually become Flower—learned a different lesson. When you do not speak, people stop expecting anything from you. When you do not speak, you become background. And when you become background, people forget you are listening.

That was the beginning of her education.

By the time Flower was sixteen, her silence had become part of the plantation’s furniture. People stopped trying to coax words out of her. They talked around her. They said things they would never say if they believed she could carry a sentence from one room to another. Flower moved through the Whitmore household and gardens like someone who belonged there but did not fully exist, and the powerful mistake people make, again and again, is assuming that invisibility means emptiness.

Edward Whitmore noticed her the way his father noticed anything he wanted: as if wanting it was justification enough. In a house where some men treated boundaries as suggestions, Edward grew up believing consequences were for other people. He told himself stories about her silence, about what it meant, about what it allowed. He mistook her lack of words for lack of memory.

Caroline noticed her too, but Caroline’s interest was never driven by impulse. It was driven by information. Caroline was not naïve about what happened in rich men’s houses. She understood how reputations were built, how they were protected, how they could be threatened. She followed patterns. She listened to half-finished conversations. She watched which doors opened late and closed early. She did not look at Flower and see only a victim. She saw leverage.

Later, Caroline would be recorded saying something that revealed the logic she lived by: that Flower was her insurance policy, that as long as Flower existed, Edward could not destroy her completely. It was not compassion. It was strategy. Caroline believed she was holding a dangerous secret by the throat.

She never considered that the secret might be holding her.

William Whitmore looked at Flower and saw something else entirely. Not a tool. Not an asset. Not a threat. He saw a symbol, and like many young men raised in comfort who discover injustice too late, he turned that symbol into a private story about himself. In his mind, he became the one who would save her. He wrote poems. He left wildflowers. He built a fantasy in which his tenderness could undo a world built on force.

He did not truly know her. He loved a version of her he invented, and inventions are easy to adore because they never contradict you.

Flower understood all of this with a clarity that came from years of listening. Edward’s hunger. Caroline’s ambition. William’s longing. Each of them believed they were acting from their own agency, steering the household with their own hands. Flower rarely moved anything openly. She rarely needed to. She watched the gravitational pull of each person’s desires, and she understood that people often destroy themselves faster when you simply let them talk, let them assume, let them step deeper into the story they want to believe.

Meanwhile, Dela was building her own plan, separate from her daughter’s, quiet enough to be missed by everyone who underestimated her. If Flower was learning the household’s secrets, Dela was learning time. She did not rush. She studied routines. She learned what could be stolen in small amounts without being noticed. She collected bits of harsh substance from places people rarely checked, dried herbs from the edge of the woods, and held them the way a person holds matches in a world full of straw.

For thirteen years, she waited.

No one—least of all the Whitmores—understood what that kind of waiting meant.

By September of 1854, the house was already full of tension even before anyone admitted it aloud. Caroline had gathered enough whispers, enough evidence of Edward’s behavior and recklessness, to believe she could break her engagement and secure a settlement that would let her leave with both reputation and resources intact. She did not want a public scandal. She wanted a controlled outcome: Edward embarrassed, the Whitmores pressured into paying her to disappear, and her future salvaged before it ever fully belonged to him.

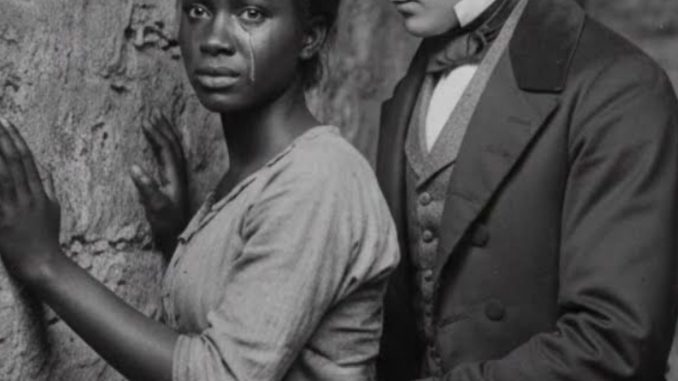

A family meeting was called in the parlor, the kind of room designed to project calm even when nothing behind it was calm at all. Windows were open to hot air. Aldrich sat with the stillness of a man who had never questioned his authority. William sat off to the side, clinging to a book like it was armor. Edward drank, his impatience sharpening with every swallow. Flower, as always, stood near the edge serving tea, invisible by design.

Caroline laid out her case with careful precision. She spoke of behavior, of propriety, of the risk Edward posed—not just to her, but to the Whitmore name. She believed she was tightening a rope around him.

Edward did not respond like a man cornered by logic. He responded like a man cornered by exposure. His face changed. His voice rose. He accused Caroline of plotting, William of weakness, his father of control. And then, as if reaching for the one thing in the room he believed could be blamed without consequence, he pointed at Flower.

She knows, he said. She’s been playing us.

The room turned.

For the first time in thirteen years, Flower did something that disturbed everyone who saw it. She lifted her eyes fully and smiled—not a warm smile, not a shy smile, but a small, deliberate expression that looked almost like recognition.

It was enough to snap something already cracked.

Edward moved toward her. William moved to intervene. Dela, hearing the commotion, arrived like a storm that had been gathering for years. Words became shouting. Bodies moved too fast for everyone to track. In a house built on control, control evaporated in minutes.

Later, people would call what happened a riot, a rebellion, a tragedy of passion. They would search for a label that let them believe it was sudden and therefore unavoidable. But the truth was that it was the result of pressure stored too long, secrets held too close, fear and power stacked on top of each other until the structure could no longer hold its own weight.

By dawn, the Whitmore house was no longer a symbol of order. It was a wrecked stage where too many lives had collided and too few had survived.

When the sheriff arrived, he found a scene he would spend the rest of his life trying to describe without feeling it crawl back into him. Members of the Whitmore family were dead. A deputy lay where panic and confusion had caught him. Dela was gone too, her long waiting ending in the most irreversible way. And in the middle of it all sat Flower.

Not hiding. Not running. Not pleading.

Sitting on the floor, soaked in evidence of what had happened around her, hands empty, face calm, as if the night had unfolded exactly as she expected.

Men who had seen battlefield injuries later admitted that what unnerved them most was not the death. It was the stillness of the girl who had lived inside that house without being seen and had now become impossible to ignore.

The investigators wanted a clean story. They wanted a single hand to blame. They wanted a motive that fit inside the moral boxes of their time. But Flower offered them nothing—no confession, no defense, no tearful explanation. The system tried threats, then bargaining, then religious appeals. Silence absorbed them all.

And so the courtroom, when it came, turned into something stranger than a trial. It became a public argument about whether a person could be guilty without touching a weapon, whether a life could be shaped by what it refused to reveal, whether silence itself could be treated as intent.

Flower stood there in chains not because anyone could prove she had struck anyone down, but because the story had to land somewhere. Caroline was a respectable white woman. The dead could not testify. The parish wanted closure, not complexity.

So the case became what powerful systems often turn complicated truths into: a lesson, a warning, a removal. A way to sweep the unsettling parts of the story out of sight.

Yet the question that lingered long after names faded from local memory was not simply who did what in that parlor and basement and hallway. The deeper question was the one that made people uncomfortable to ask out loud, because it pointed back at the world they lived in.

If you train a child to survive by becoming invisible, what kind of power do you accidentally create?

If you build a household—and a society—on secrets and force, what happens when the people who were never allowed to speak learn to listen perfectly?

Flower’s hands were empty. That much was true.

But Louisiana learned, in the hardest way, that empty hands do not always mean absence of influence, and that sometimes the most dangerous presence in a room is not the one holding a weapon.

It is the one who has been watching all along.