When people talk about the end of the Crusades, the focus usually lands on battles, shifting borders, and dynasties rising or falling. But for countless civilians—especially women—“the end” did not feel like closure. It felt like a transition from open conflict to a new kind of control: bureaucratic, household-based, and designed to absorb conquered populations into an unfamiliar system.

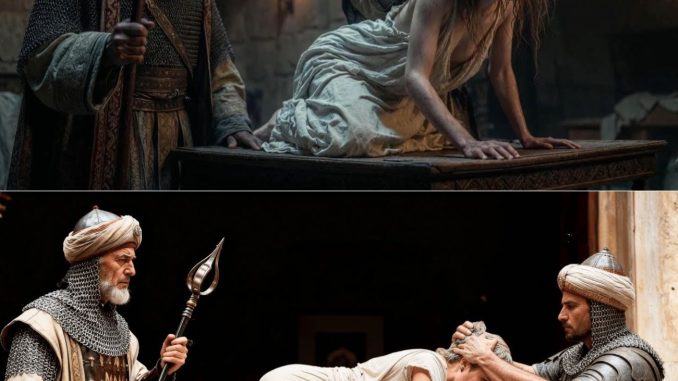

Stories like the one later attributed to a Christian woman called Catherine—captured in the mid-thirteenth century and processed through Mamluk institutions—often survive in fragmented form: hints in legal records, household ledgers, and later retellings shaped by moral outrage or narrative drama. The details can vary, and modern retellings frequently exaggerate for shock. Still, the broader themes the story points to are historically meaningful: conquest, captivity, forced cultural adaptation, and the complicated legal realities of slavery and manumission in medieval societies.

This article reframes the narrative in a policy-safe, educational way. It does not romanticize conquest or reduce suffering to entertainment. Instead, it explains why “rewriting” a person’s life—changing language, status, name, household role, and identity—could be more socially effective than simple brutality, and why some individuals sought agency through the very rules that restricted them.

Damascus in a Changing World

By the 1260s, the eastern Mediterranean was undergoing rapid transformation. Crusader strongholds were weakening, and new power structures were consolidating across the region. In that environment, cities like Damascus were not just military targets; they were administrative hubs. They held courts, markets, training networks, and complex household economies that required labor, skills, and organization.

The Mamluk system itself was distinctive. The ruling military elite was largely composed of men who had entered the society through servitude and training. Many were brought as youths, converted, educated, and integrated into disciplined structures that rewarded loyalty and competence. This origin story mattered because it influenced how the state perceived “integration”: not as a gentle cultural exchange, but as a managed process that could reshape people into functional members of a hierarchy.

That framework, in turn, shaped how newly captured populations were handled. Rather than leaving everything to chaos, authorities and households often relied on classification: age, language, health, skill level, and perceived adaptability. In other words, captivity could be administered, not only enforced.

A Family’s Calculation—and Its Limits

In the story version often told, Catherine’s father is described as a merchant who believed that paperwork, connections, and negotiated promises could shield his family. That belief is understandable: merchants often lived by contracts and relationships that crossed political boundaries. They relied on networks, guarantees, seals, and intermediaries.

But war has always had a way of nullifying the logic of commerce. In moments of conquest, personal protections could collapse quickly—especially when the actors on the ground were not the same people who signed agreements in calmer settings.

Whether or not every detail of the tale is literally true, the underlying point stands: during upheaval, civilians could be separated, displaced, and absorbed into new structures with little warning. Families were often fractured. Survivors were left with missing relatives, uncertain fates, and years of not knowing.

Processing as Policy: How Systems Create “Order” After Violence

A major theme in the narrative is that captured women were not treated as individuals with a future of their own, but as “units” to be assigned. The story describes an administrator who interviews captives, tests language ability, and sorts them into different pathways.

In educational terms, this reflects a real dynamic common to many historical slave systems: institutional sorting. People were evaluated for labor potential and placed accordingly. Some were directed toward hard physical work. Others were placed in domestic settings. A smaller number—those with literacy, numeracy, or language skills—were used in administrative or household management roles.

This is one reason historical accounts can feel chilling even without graphic detail: the harm is not only personal; it is structural. When suffering becomes organized, it can appear “reasonable” to the people running it. That is exactly how systems endure—through routine, paperwork, and normalized roles.

“Integration” as Identity Replacement

The most important idea the story tries to communicate is not simply captivity, but identity replacement: the gradual erasure of language habits, social cues, and personal belonging until a person becomes legible inside the new order.

In the narrative, an older woman serves as a trainer—someone who once endured the same system and now instructs newcomers in what to say, how to behave, and how to survive. Whether this specific character existed or is a storytelling device, the pattern is plausible historically: institutions often rely on intermediaries, and those intermediaries are sometimes people who were previously subjected to the system themselves.

The mechanisms described—language correction, etiquette training, household hierarchy, document formats—are “soft” controls rather than overt force. Yet soft controls can be powerful because they reshape daily life. Over time, people may learn to avoid words that mark them as outsiders, adopt new norms, and perform compliance not only to avoid punishment but to reduce friction and danger.

That is what “rewriting” means in this context: not changing the past, but changing what a person is allowed to be going forward.

Literacy as a Double-Edged Skill

A key turning point in the story is Catherine admitting she can read and write. Literacy becomes both protection and vulnerability.

It can be protection because skills create value. In many historical systems, a person with a specialized skill could be less “disposable” than someone assigned to exhausting labor. Literacy could lead to work that was physically safer and more stable.

But literacy also binds a person more tightly to the institution. If your value is tied to administrative service, you may be kept inside elite households and drawn deeper into their social and political networks. You are closer to power, but not part of it. You may have information, but not authority. You become useful in ways that make escape harder.

This is why the story’s emotional logic resonates: survival is not the same as freedom.

Household Life as an Institution of Control

The narrative emphasizes that elite households operated like small governments: ranks, rules, staff, schedules, responsibilities, and careful supervision. That is historically consistent with how large households functioned in many places and eras. Households were economic units. They managed labor, finances, alliances, and reputations.

If someone like Catherine served as a letter-writer or recordkeeper, she would be part of the household’s operating system—helping maintain social ties, gift exchanges, negotiations, and documentation. Her work could be mundane on the surface, but it supported the broader structure of influence.

This is also where many sensational retellings cross a line—turning household control into explicit sexual narrative. For a policy-safe educational rewrite, it’s enough to say: captivity in elite households could involve multiple forms of coercion and lack of consent, and it created long-term psychological survival strategies. We don’t need explicit reenactment to understand that such conditions can be damaging and dehumanizing.

The Petition: Using the System’s Rules Against It

One of the most interesting parts of the story is the moment Catherine seeks manumission (formal release from enslavement) by petitioning through legal and administrative channels.

In many Islamic legal traditions, manumission was a recognized practice, though it varied across time and place. People could be freed through purchase, reward, religious encouragement, contractual arrangements, or at the discretion of the owner. It was not an automatic guarantee. But it existed as a concept within the legal landscape—meaning a skilled person could sometimes argue for freedom using the society’s own rules.

The narrative frames Catherine’s petition as strategic: she cites long service, documented contributions, and precedents; she chooses a public moment when denial would carry reputational cost. Whether the exact scene happened that way is hard to verify, but as a structure, it reflects how agency can emerge even in restrictive systems: people study the rules, learn the language of legitimacy, and look for moments where power has incentives to appear lawful.

In other words, the petition is less about a heroic speech and more about administrative leverage.

Freedom That Isn’t Escape

The story’s ending is deliberately complicated: Catherine receives legal freedom but remains within the same social world. She becomes a paid worker inside the structure that once owned her. She has protection from sale, but not a restored past. The places she came from may no longer exist as they once did. Family ties are broken. Identity has been reshaped by years of forced adaptation.

This is an uncomfortable but important historical truth: manumission can be real and still incomplete. Legal status changes faster than lived reality. Even after freedom, people often remain economically dependent, socially constrained, and culturally isolated. They may have no safe route “home,” or no “home” left to return to.

So the story’s most lasting lesson is not a clean triumph. It is the idea that systems can take so much that even liberation feels narrow.

What This Story Gets Right—Even If Some Details Are Stylized

Modern viral retellings often mix fact, plausibility, and invented dialogue. That’s why it’s important to separate the sensational packaging from the historically meaningful themes.

The story gets several big ideas right:

- Captivity after conquest often led to long-term absorption into new social structures, not simply short-lived imprisonment.

- Institutions can normalize cruelty through routines, paperwork, and “reasonable” procedures.

- Language and etiquette are tools of power, used to mark insiders and outsiders.

- Skills like literacy can increase survival odds while also increasing entanglement.

- Agency sometimes appears through legal literacy, petitions, and strategic use of precedent.

- Freedom can be partial, especially when family, community, and homeland have been erased.

And it also points to something that matters today: the most durable harm is often the kind that is organized, defended as normal, and carried out by people doing “their jobs.”

Why Remembering Matters

History is not only a list of rulers and battles. It is also a record of how ordinary lives were redirected by institutions—how identities were managed, how families were dissolved, how survival required adaptation, and how rare acts of agency could emerge from careful understanding of the rules.

Whether or not “Catherine” existed exactly as described, the category of experience does not need to be doubted: many women lived through conquest, captivity, and forced cultural reshaping. Their stories are often absent because the archives were built by those with power. When a voice appears—even indirectly—it is worth handling responsibly: without sensationalism, without graphic reenactment, and without turning pain into entertainment.

If you want, I can do one of these next (still AdSense-safe):

- Version 2 in the same “Family Stories” tone but less academic, more emotional—still without explicit sexual content

- A shorter 1,000–1,200 word version optimized for Facebook long-form

- A “debunk / fact-check” version that flags which parts are likely dramatized and which are historically grounded