June 14, 1973.

Danny Crawford stood on County Road 22 outside Grundy Center, Iowa, holding everything he owned in a worn duffel bag. He was seventeen. The door had shut behind him for the last time, and the final sentence from his stepfather still rang in his head like a slammed gate:

“You’re seventeen now. You can figure it out. Get out.”

His mother had been there, tears on her face, hands trembling at her sides. But she didn’t step between them. She didn’t argue. She didn’t say, “Stay.” She just cried while Danny’s clothes were shoved into a bag and the world he knew was cut loose.

Now he stood at the roadside as the sun lowered into the cornline. His stomach felt hollow, not only from fear, but from the sudden understanding that nobody was coming to fix this for him.

He had $47 in his pocket. No car. No job. No place to sleep. No relative whose number he could call. No family that wanted him.

A farm truck slowed and pulled onto the shoulder.

An older farmer stepped out, boots crunching on gravel. He studied Danny for a moment the way farmers study weather—quiet, careful, trying to read what isn’t being said.

“You need a ride, son?” he asked.

Danny swallowed. He nodded.

The farmer opened the passenger door and waited until Danny climbed in. The cab smelled like dust, coffee, and the faint sweetness of hay. The truck rumbled back onto the road.

They drove in silence for several miles. The farmer didn’t press him. He didn’t perform kindness like a show. He just drove like it was the most normal thing in the world to pick up a kid with a duffel bag at sunset.

Finally, he asked, “Where you headed?”

Danny stared out at the passing fields. “I don’t know,” he admitted.

“You got family somewhere?”

“No, sir.”

“What happened?”

Danny hesitated, then said the simple truth. “Got kicked out.”

The farmer nodded as if he’d heard that story more times than he wanted to count. “How old are you?”

“Seventeen. Graduated last month.”

“You got work lined up?”

“No, sir.”

“You got any skills?”

Danny’s voice came out tight. “I can work. I’m strong. I learn fast.”

The farmer didn’t answer right away. He kept driving, hands steady on the wheel, eyes forward. Then he turned his head slightly.

“I’m Earl Mitchell,” he said. “I could use help on my farm. Can’t pay much. Eighty dollars a week. You could sleep in my machine shed for now, till we sort out something better. You interested?”

Danny felt something hot rise in his throat—panic, relief, disbelief, all tangled together. He forced himself to breathe through it.

“Yes, sir,” he managed. “Thank you.”

That’s how, at seventeen, Danny Crawford became a hired hand, sleeping on a cot in Earl Mitchell’s machine shed and working from sunrise to sundown for eighty dollars a week.

It wasn’t comfort. It wasn’t security. But it was a chance.

Earl farmed four hundred acres of corn and soybeans. He had decent equipment and a careful way of doing things, but he was sixty-eight and slowing down. He needed someone who could keep up with the pace the land demanded.

Danny threw himself into the work with the intensity of someone who understood what hunger felt like—hunger for food, yes, but also hunger for stability. He learned fast. Within two weeks, Earl trusted him to run equipment. Within a month, Earl stopped watching over his shoulder.

Danny saved every dollar he could. He ate simply. He wore the same work shirts until the seams thinned. He didn’t go into town unless it was necessary. After three months, he had saved $940.

Earl let him use an old 1962 Chevy pickup that barely made it down the lane without complaining. Danny fixed it himself with salvage-yard parts and Earl’s tools. Something in him liked the process: broken thing, patient hands, working thing again. It felt like a language he could learn.

One Saturday in September, Danny saw a small ad in the Grundy Register:

“Farmall H tractor for sale. Needs work. $100. Call Robert.”

Danny stared at the words longer than he should have. A hundred dollars was almost everything he had fought to protect. It was also the kind of price that only existed when nobody else wanted the problem.

He called.

He drove to see it on a Sunday afternoon, following directions down a gravel road to a sagging shed behind a modest farmhouse. The tractor sat inside like a forgotten animal, heavy and still. A 1948 Farmall H that hadn’t run in five years. The tires were flat. The paint was faded into a dull memory of red. Rust had crept along the metal like time leaving fingerprints.

The owner, Robert Hayes, was seventy-four. He leaned on the doorway and watched Danny walk slow circles around the machine.

“I bought it new in ’48,” Robert said. “Used it till ’68. Been sittin’ since. I don’t have the energy to tinker with it anymore. I just want it gone.”

He squinted at Danny. “You really want this thing?”

Danny ran a hand over the hood. The metal was cold. The tractor felt like it had been abandoned, but not finished.

“Yes, sir,” Danny said. “I’ll give you a hundred if you let me work on it here until I get it running. Then I’ll haul it away.”

Robert chuckled, half amused, half curious. “Deal.”

Danny paid the hundred dollars—almost everything he’d saved—and walked away with $840 left.

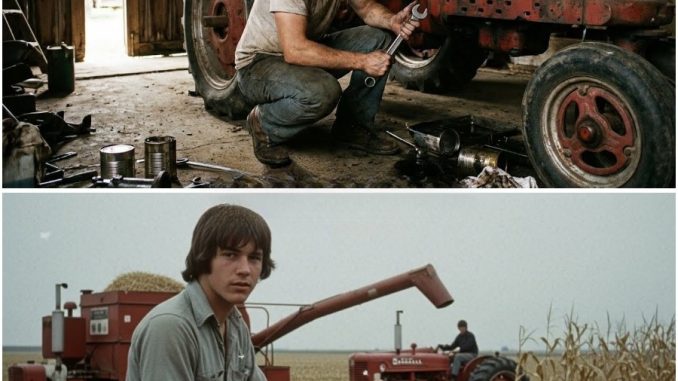

Over the next six weeks, he spent every Sunday in that shed, sleeves rolled up, hands blackened with grease, mind locked on the puzzle in front of him. Earl lent him tools and offered quiet guidance, but mostly Danny figured it out himself.

He soaked the cylinders with penetrating oil for two weeks, returning again and again, coaxing the seized engine like you coax a stubborn door in an old house—patient pressure, not brute force. He worked the pistons loose. He rebuilt the carburetor with a cheap kit. He cleaned the fuel system. He replaced plugs and overhauled the magneto. He hunted down used tires at a salvage yard—forty dollars for all four—and mounted them himself.

Then he scraped off loose rust, primed the exposed metal, and repainted the tractor International Harvester red. Paint and supplies cost him fifty-eight dollars. The color didn’t just make it look better. It made it look like something worth owning.

By the end of October, the Farmall H ran.

Not perfectly. It smoked a little. It made strange noises the first few minutes like it was clearing its throat. But it ran. It could pull. It could work.

For the first time in his life, Danny owned something that mattered—something he had brought back with his own hands.

Earl came to see it.

He walked around the tractor, nodded slowly, then looked at Danny with a kind of respect that didn’t need words.

“That’s good work,” Earl said. “Real good. What’re you gonna do with it?”

Danny wiped his hands on his jeans. “I don’t know yet,” he said. “But I will.”

That first winter nearly broke him.

November 1973 through March 1974 was an Iowa winter that didn’t care about hope. The machine shed wasn’t heated. The wind slipped through cracks in the walls. Some mornings Danny woke up with frost on his blankets. He could see his breath inside. His fingers felt stiff, like they belonged to somebody else, until he rubbed them back to life.

He had a cot, three blankets, and a small space heater that did its best but never quite won.

He didn’t complain. He didn’t ask Earl for more. He was terrified that if he asked for anything, he’d be reminded he was only there by permission, and permission could be taken back.

Some nights he sat by the heater reading farm magazines Earl had given him—crop rotation, soil management, equipment maintenance. He studied like it was school, except this school could determine whether he ate.

Other nights he thought about his family.

He wondered whether his mother thought about him. Whether she ever stood in that kitchen and wished she had spoken up. He usually decided she hadn’t. That was easier than hoping.

“The loneliness was worse than the cold,” he would later tell Sarah. “The cold hurt, but it didn’t reject you. The loneliness did.”

The Farmall became therapy.

When you’re seventeen and the world has declared you disposable, fixing something that others call junk feels like rebellion. It feels like proof. Every bolt he tightened, every stubborn piece he coaxed back into function, was a quiet message to himself: I can make things work. I can stay.

That winter, Earl got sick.

Pneumonia put him in the hospital for three weeks. Danny ran the farm alone—feeding cattle, doing maintenance, keeping everything from falling behind. He moved through each day with the steady fear of making a mistake he couldn’t afford. But he didn’t stop. He couldn’t.

When Earl came home in January 1974, thinner and weaker, he pulled Danny aside.

“You saved this place while I was gone,” Earl said. “I owe you more than I paid you.”

Danny shook his head. “You gave me a chance when nobody else would,” he said. “We’re even.”

Earl’s expression didn’t soften. “No,” he said. “We’re not. But we will be.”

In March 1974, Earl made an offer that changed the direction of Danny’s entire life.

“I’m seventy now,” Earl said. “Can’t farm like I used to. I don’t have kids. My nephew’ll inherit this land, but he doesn’t want to farm. He’ll sell it when I’m gone.”

He looked at Danny. “How’d you like to rent eighty acres from me? Farm it yourself?”

Danny stared at him, unable to process the words at first.

“I don’t have equipment,” he said. “Just that old Farmall.”

“That Farmall can handle eighty acres if you’re patient,” Earl replied. “I’ll rent you the land for four thousand a year. Pay me after harvest. If you make it work, we expand next year.”

Danny’s throat tightened. “Why would you do that for me?”

Earl shrugged. “Because you remind me of me,” he said. “Somebody gave me a chance once. I’m giving you one.”

That spring, eighteen-year-old Danny Crawford rented eighty acres.

He used his Farmall H and borrowed Earl’s planter and cultivator. He planted corn across every acre. He was still living in a machine shed, farming with a tractor he had dragged back from silence for a hundred dollars.

He worked harder than he’d ever worked in his life.

Days were Earl’s four hundred acres. Early mornings and late evenings were his own eighty. He slept maybe five hours a night. He ate fast. He lived tired. But he felt something he hadn’t felt before: direction.

The corn grew well. The weather cooperated. No major disasters. Just a long season of work and waiting.

Harvest came in September.

Danny borrowed Earl’s combine. He had never run one alone before. The thought of damaging it made his stomach knot. The thought of ruining his first crop was worse.

But he climbed into the cab, started cutting, and learned as he went—slow at first, then steadier as the rows fell behind him and the grain tank filled.

Load by load, he hauled grain to town and sold it. At the elevator, he held the checks in his hands and understood what they meant.

This wasn’t a paycheck handed to him by someone else.

This was money he had created.

The eighty acres yielded 112 bushels per acre—8,960 bushels. Corn sold for $3.70 a bushel. The gross was $33,152.

After paying Earl the $4,000 rent, plus seed, fertilizer, fuel, and other costs, Danny cleared around $16,400.

Eighteen years old, farming eighty acres with a $100 tractor, and he had made sixteen thousand dollars profit.

He sat in the truck outside the elevator, stared at the checks, and cried—quietly, like the sound didn’t matter. He wasn’t crying because he was sad. He was crying because, for the first time since that roadside evening, he believed he might actually be okay.

That night, he called home.

His stepfather answered.

“Who is this?”

“It’s Danny,” he said. “Can I talk to Mom?”

“She doesn’t want to talk to you.”

Danny heard his mother’s voice faintly in the background. “Who is it?”

“Nobody important,” his stepfather said, and the line went dead.

Danny never called again.

From 1974 through 1981, he expanded slowly and carefully.

He didn’t chase big leaps. He didn’t buy shiny machines to prove anything. He didn’t drown himself in debt because he had lived too close to the edge to ever trust borrowed comfort.

He paid cash. Always.

1975: He rented 160 acres, still using the Farmall and Earl’s equipment. He bought a used 1964 Ford tractor for $1,200.

1976: He rented 240 acres. He bought a used disc and planter.

1977: He rented 320 acres from Earl and another 80 from a neighbor. He bought his first combine—a 1968 John Deere—for $9,000 cash.

1978: At twenty-two, he was farming 700 acres and had saved $94,000. Earl, now seventy-five, stepped back from active farming and let Danny operate all four hundred acres.

By 1981: Danny was twenty-five, farming 1,200 acres, making over $100,000 a year, with $230,000 in savings.

His lifestyle barely changed.

In 1980, he moved out of the shed into a small trailer on Earl’s property. It cost $4,000 and felt like a palace: heat, running water, a real kitchen. He drove the patched-up ’62 Chevy until 1984 when the frame finally cracked. Then he bought a used ’79 Ford for $2,800.

He wore Carhartt overalls until they were threadbare. He owned three pairs and rotated them until each one looked like it had lived a hard life. People assumed he was barely making it.

They didn’t know about the savings. They didn’t know he was building something steady and quiet, like a field growing under snow.

When Earl died in January 1982, his nephew put the four hundred acres up for sale. Asking price: $320,000.

Danny faced the biggest decision of his life.

He had $230,000 saved. He could borrow the rest, but he hated debt. He could walk away and keep renting. But this land wasn’t just acreage. It was the place where he’d been given a chance. It was the ground where he’d learned survival and then turned survival into a plan.

He thought about it for two weeks. He barely slept.

Finally, he decided he would offer $280,000 in cash. If the nephew refused, Danny would walk away. No loans.

The nephew accepted immediately.

“Cash closes fast,” he said. “I want it done.”

Danny sold a bit of equipment and drained his savings to raise the $280,000. They closed in March 1982.

At twenty-six, Danny Crawford owned four hundred acres.

That first night, he walked the boundaries alone. The stars were sharp above him, the land quiet under his boots. He kept thinking about the boy on the roadside with $47 and a duffel bag, and about how the most important thing that had happened to him wasn’t money.

It was being allowed to stay.

In 1983, Danny met Sarah at church.

She was twenty-four, an elementary school teacher, raised on a farm, practical in the way farm kids often are. She understood the hours, the uncertainty, the rhythm of seasons that didn’t care what you wanted.

They married in 1984. Sarah moved into Danny’s small trailer and never made him feel ashamed of it.

“We’ll build something nicer when we can afford it,” she said, as if it was the simplest truth in the world.

Their first child, a son, was born in 1985. They named him Earl Mitchell Crawford, after the man who had saved Danny’s life. Their second child, Grace, arrived in 1987.

In 1989, they built a modest house on the land—1,600 square feet, three bedrooms, nothing fancy. They paid $48,000 cash. Danny stood in the doorway the first night and listened to the quiet, not the lonely quiet of the shed, but the safe quiet of a home where someone waited for you.

When Danny’s mother died in 1989, Sarah encouraged him to go to the funeral.

“You’ll regret it if you don’t,” she said.

Danny went. His stepfather ignored him. His half-siblings barely acknowledged him. Danny paid respect at the graveside and left.

“Do you wish it had been different?” Sarah asked later.

“Every day,” Danny said. “But wishing doesn’t change anything. I built my own family now. That’s what matters.”

By 1990, Danny owned eight hundred acres and rented another thousand. His net worth was around $1.4 million.

By 2000, he owned 1,400 acres, rented 1,200, and his net worth climbed to roughly $2.8 million.

In 2010, at fifty-four, a Farm Journal reporter sat with him for an interview.

“You were kicked out at seventeen with $47,” the reporter said. “Now you’re worth over three million. How?”

Danny didn’t answer fast. He wasn’t the type to dramatize himself.

“I bought a $100 tractor nobody wanted,” he said. “Fixed it. Used it to farm eighty acres. Made sixteen thousand dollars the first year. Put it back into the land. Never stopped. Took a long time. But I built it.”

“What happened to your family?” the reporter asked.

Danny’s face tightened in a way that suggested the question still carried weight.

“My mother died in ’89,” he said. “We never made it right. I tried a few times, but it didn’t happen.”

“Do you forgive them?”

Danny stared at the table for a moment. “Some days yes. Some days no. But I don’t carry hate anymore. They made my start harder. But maybe that’s what pushed me to build something. I don’t know. I just know I’m here.”

“What did Earl Mitchell mean to you?”

Danny’s eyes watered, fast and unexpected.

“Earl saved my life,” he said. “He took in a scared kid and gave him work, and time, and a chance to become something. I named my son after him. Everything I built stands on that first chance.”

“And the Farmall?” the reporter asked. “The one you bought for a hundred dollars?”

Danny’s voice softened.

“Still got it,” he said. “Still runs. It’s in my shed. I start it up once a month, keep it maintained. That tractor is my whole journey—from nothing to something. I’ll never sell it. When I’m gone, it goes to my kids, with one instruction: keep it.”

The article ran in April 2010 under the title:

“From a $100 Tractor to a $3 Million Farm: The Danny Crawford Story.”

Tens of thousands of people wrote in. Young farmers said it gave them hope. Parents said they’d share it with their kids. People in different industries said the lesson felt the same: start where you are, fix what you can, and keep showing up.

Danny wrote back to every single one.

In 2015, Iowa State University invited him to speak to their agriculture program. The topic was “Building Success From Nothing.”

Danny trailered the Farmall H to campus and parked it outside the auditorium, red paint still shining, engine still ready to work.

Inside, eight hundred students filled the seats.

Danny told his story: the roadside in 1973, the machine shed, the tractor restoration, the first winter, the first eighty acres, the slow expansion, buying Earl’s land, building a family.

Then he took them outside and placed his hand on the tractor’s fender like you place a hand on an old friend.

“This tractor taught me something,” he said. “Broken doesn’t mean worthless. Patience can beat problems that look too big. And value isn’t what something looks like. It’s what it can do when you give it the chance.”

He looked at the students.

“You don’t need everything to start,” he said. “You need one thing that works and the willingness to work with it. Don’t underestimate small beginnings.”

The students applauded, then lined up to touch the tractor, to take photos, to ask for advice that sounded less like a speech and more like a blueprint.

In 1998, when his son Earl turned thirteen, Danny pulled the tarp off the Farmall in the shed.

“This tractor changed my life,” he told him. “Now you learn on it.”

Earl learned to drive on that 1948 Farmall the same way his father had learned to survive: slowly, carefully, respecting the machine, respecting the work. Later, when Earl graduated high school, Danny handed him the keys.

“It’s yours,” he said. “Maintain it. Use it. And one day pass it forward. Don’t sell it.”

Earl promised. Earl kept the promise.

By 2024, Danny was sixty-eight. His son ran most of the 1,800-acre operation now. Danny still helped, still watched the fields with the quiet attention that had saved him since he was seventeen. His net worth was around $4.2 million, built over decades, starting from $47 and a machine shed.

He’d also helped more than forty young farmers get started—renting land at fair rates, mentoring them through their first seasons, warning them gently about debt and rushing.

His advice never changed.

“Start with what you have. Fix what’s broken. Work harder than you think you can. Save aggressively. Build slowly. And never forget where you came from.”

There was a rule in Danny’s home: anyone who visited had to see the Farmall. They had to hear the story. They had to understand that success isn’t about where you begin, but what you do with what you’re given.

On the wall, two photos hung side by side.

June 14, 1973: Danny on the roadside, thin and stunned, holding a duffel bag.

September 1974: Danny sitting on the restored Farmall, farming his first eighty acres.

One year apart.

A lifetime of meaning in between.

And somewhere in Iowa, a 1948 Farmall H still started on an ordinary morning—engine turning over steady, like proof that the smallest thing, rescued and kept alive, can carry a person farther than anyone ever expected.