There are moments in war that become legend not because they are glamorous, but because they force everyone who hears them to re-measure what they thought was possible.

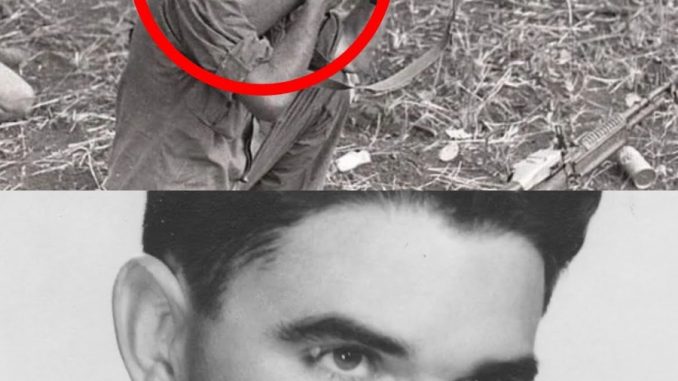

In the summer of 1967, one of those moments began with a feeling Gunnery Sergeant Carlos Hathcock didn’t like admitting to: a flicker of uncertainty. Not panic. Not hesitation. Just the cold awareness that somewhere out there, a skilled opponent had started writing a message in the only language snipers share—distance, patience, and intention.

Hathcock had already earned a reputation that traveled faster than any radio. Marines knew him as the calm presence behind a scope, a man who could read wind the way others read clocks. The opposing side, according to accounts often repeated among American troops, gave him a name tied to the small white feather he sometimes wore—something that wasn’t supposed to be a challenge, but became one anyway.

And challenges, in that world, were never just personal. They were strategic. Psychological. Designed to tilt the balance long before a trigger was ever touched.

That’s how the jungle felt when the rumor started spreading about a North Vietnamese sniper nicknamed “Cobra”—a specialist supposedly selected for one purpose: to hunt the hunter.

Whether every detail of that story was true didn’t matter as much as the effect it had. Stories like that get into men’s heads. They make you listen harder to silence, stare longer at shadows, second-guess the obvious.

Then one day, Hathcock came across something that made the warning feel real—an unmistakable sign that an enemy sniper was not only nearby, but thinking about him specifically.

It wasn’t bravado that pushed him forward after that. It was duty, stubbornness, and the hard truth that in a conflict like Vietnam, unseen threats could shape entire operations. If there truly was a sniper out there targeting Marines—targeting him—then leaving the problem alone wasn’t just risky. It was irresponsible.

So he moved.

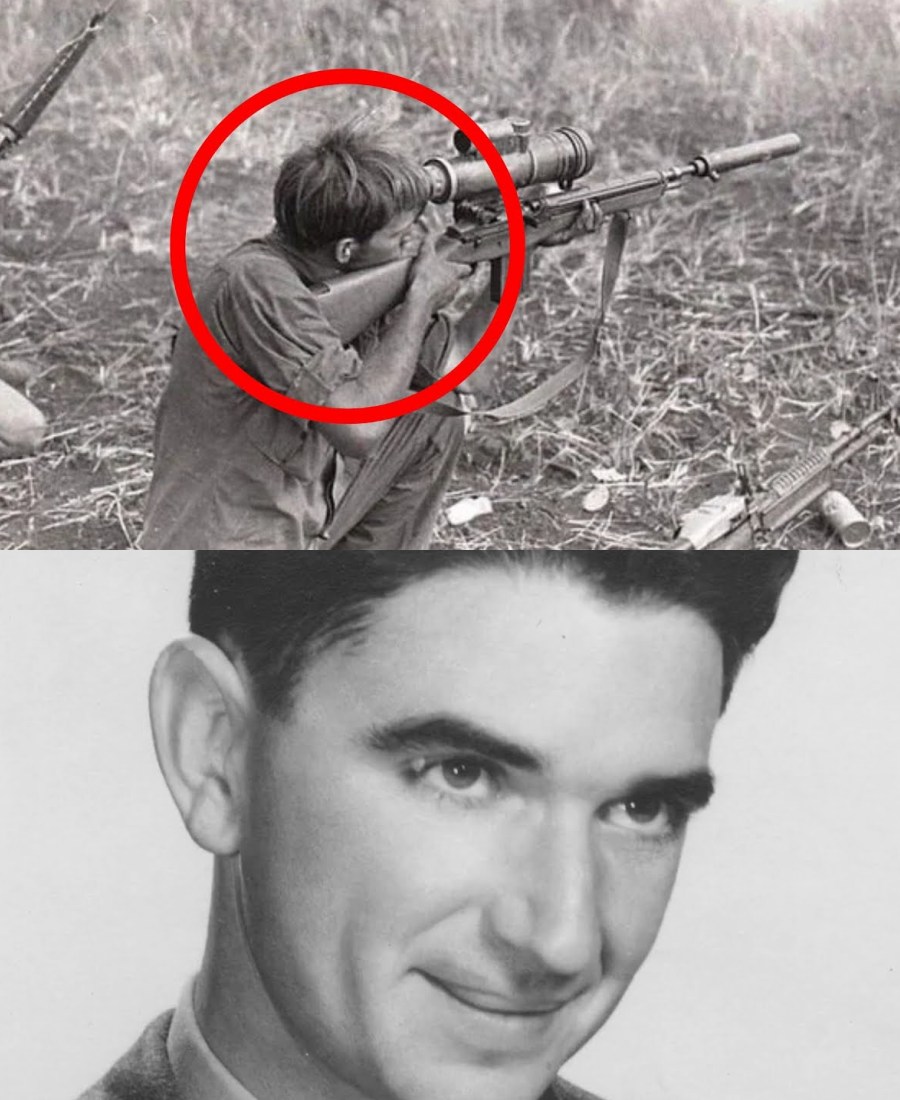

And his spotter moved with him.

They didn’t walk into the jungle like action-movie heroes. They crawled, slowly, uncomfortably, hour after hour, their bodies pressed into the ground. They became students of insects, mud, heat, and the thin line between a branch that’s just a branch and a branch that hides a human eye.

This wasn’t romantic. It was work.

And the jungle didn’t care about reputations.

Born With a Rifle in His Future

Long before Vietnam, long before whispers of Cobra, Hathcock’s life had been shaped by a kind of poverty that teaches you practical skills early and unforgivingly. Food didn’t appear because you needed it. Warmth didn’t happen because you deserved it. If your family was going to get by, somebody had to bring something home.

For Hathcock, that “something” was often a small animal taken cleanly, quickly, with the kind of shot that doesn’t waste ammunition or energy. He learned discipline the way other kids learned games: through repetition and necessity.

There’s a difference between shooting for sport and shooting because missing has consequences. In one world, you shrug and try again. In the other, you go to bed hungry.

By the time he was old enough to think seriously about the future, he wasn’t dreaming of comfort. He was dreaming of the Marines. Not because he romanticized war—but because the Marine Corps represented purpose, identity, and a path out of the narrow life he could see in front of him.

When he enlisted, he didn’t arrive as a loud prodigy. He arrived as a young man who could endure discomfort without needing to talk about it.

That became his advantage.

Boot camp breaks some people not because it is impossible, but because it is relentless. Hathcock absorbed it. He learned to keep his mind quiet when everything around him demanded reaction.

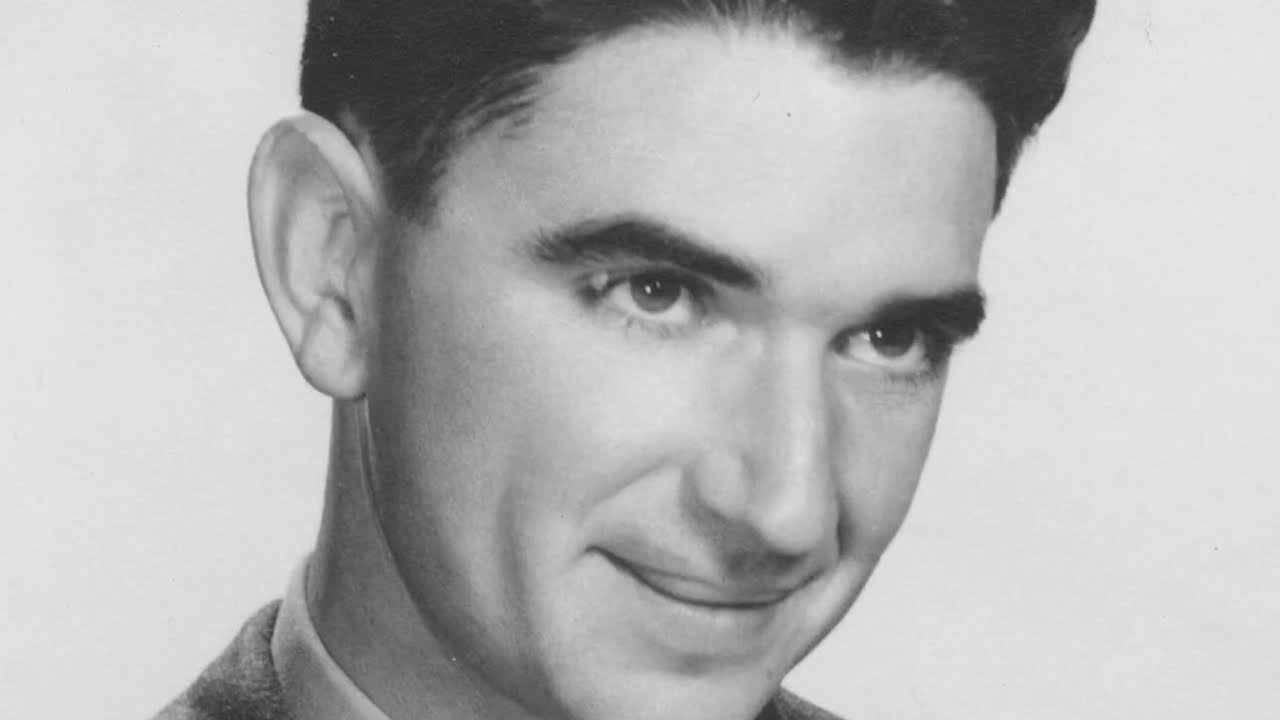

Later, when he found competitive marksmanship, his talent had a place to become measurable. Scores and targets don’t care about personality. They don’t care about your background. They care about whether you can do the thing—again, and again, under pressure.

He practiced until positions that felt painful became normal. He repeated drills until “good” was no longer enough. He didn’t chase attention. He chased consistency.

And consistency at the extreme becomes intimidating.

The Day He Proved It at Camp Perry

In the world of competitive rifle shooting, certain places carry a kind of weight. Camp Perry in Ohio is one of them—a proving ground where the best shooters in the country gather under conditions that punish arrogance.

At long distance, you don’t just fight your own nerves. You fight wind you can’t feel at your position. You fight mirage, heat distortion, tiny shifts in conditions that turn a perfect shot into a near miss.

Hathcock had already built his reputation inside the Marine Corps shooting community, but Camp Perry was a different kind of stage. It wasn’t about being good in your unit. It was about standing among the best and staying calm when one mistake can erase a year of effort.

He did what he always did: narrowed the world.

Not in a dramatic way. In a practical way. Wind. Breath. Trigger. Follow-through. Data. Adjustment. Repeat.

He won. Not by luck. By the same methodical control that would later define his battlefield reputation: the ability to keep the mind quiet, the hands steady, and the attention locked onto what mattered.

To outsiders, a long-range championship might sound like a footnote. To the Marines preparing for combat, it sounded like a signal: this man could perform under pressure in a way that wasn’t common.

And soon enough, Vietnam demanded that kind of uncommon.

Vietnam Wasn’t a Range

The battlefield didn’t reward clean conditions. It didn’t offer neat lanes, predictable flags, or a calm firing line. In Vietnam, distance came with haze. Wind came with humidity. A target was rarely a target in the clear. It was a fragment: a movement, a shape, an odd line that didn’t belong.

And the stakes were not medals. They were patrols returning, convoys surviving, Marines not being surprised.

Hathcock arrived with a rifle and the habits he had forged over years—habits that mattered when fatigue, heat, fear, and moral weight tried to shake a person loose from discipline.

War also confronts you with realities that training can’t make comfortable.

In stories told about Hathcock, one early incident is often described as a moment that haunted him: the sight of a young courier moving weapons and ammunition. It’s one thing to talk about tactics in a briefing. It’s another to face how war pulls the young into its machinery.

What matters for understanding Hathcock is not the sensational version of that incident. What matters is the moral collision.

He was a Marine. His job was to protect other Marines. But he was also a human being, confronted with the kind of situation where every option leaves a mark.

Many veterans carry that kind of memory: not only what they did, but what the circumstances demanded, and how the mind tries—unsuccessfully—to file it under “normal.”

Hathcock kept going anyway. Not because it got easier, but because the mission continued.

The Rival in the Green

Over time, the idea of Cobra grew. Marines talked the way soldiers always talk: in fragments, rumors, sharp warnings passed down the line. Sometimes those stories are exaggerated. Sometimes they’re close enough to the truth to be dangerous.

But then there were signs that felt deliberate—like the enemy wanted Hathcock to know someone was watching.

A skilled sniper doesn’t just aim at bodies. He aims at behavior. He aims at fear. He aims at decision-making. The goal is to make the other side cautious, slow, uncertain. To make them waste time.

And if you can make the best sniper in the area start calculating too much, you’ve already changed the battlefield.

Hathcock’s spotter, John Burke, understood that dynamic. A spotter isn’t a passenger. He’s the second half of the weapon system. He reads what the shooter can’t. He watches angles, distances, movement, and the strange stillness that means “someone is there.”

Together, they began to track the threat—not by charging into danger, but by reading patterns. Snipers are patient by design. They wait. They observe. They let time reveal habits.

The jungle, however, makes patience expensive. It drains you. It tests your concentration. It tempts you to shift when you shouldn’t, to move when stillness is safer.

At some point, they realized the enemy had set a kind of invitation. A trail that looked too neat. A pull in a certain direction.

Bait.

The clever part of bait is that it doesn’t feel like a trap. It feels like a lead.

And leads are hard to ignore when Marines are being targeted.

So they took it.

The Crawl That Turned Into a Lesson

Hours of crawling changes your relationship with the world. Every inch is earned. Every sound has meaning. Your body becomes a slow machine—elbows, knees, breath, pause.

In many retellings, this hunt becomes dramatic, even cinematic. But the reality of crawling through the jungle is more like endurance than heroism. Sweat finds every seam in your gear. Mosquitoes don’t care that you’re a legend. The ground presses back.

The danger is not always a sudden explosion. Sometimes it’s the quiet realization that your opponent is waiting in a place you can’t see.

At one moment, Burke sensed something wrong. A feeling that wasn’t mystical—just the subtle shift that comes when a trained man notices the pattern has changed.

And then came the crack of a shot somewhere out in the green.

Both men flattened instantly, as if gravity had increased.

In that instant, the hunt became what it always becomes when two skilled snipers meet: a contest measured in seconds, angles, and tiny mistakes. The next movement could be fatal. The next breath taken at the wrong time could reveal a position. The next decision could end everything.

There’s a special kind of pressure in that situation. In a firefight, chaos spreads risk across many people. In a sniper duel, risk narrows until it feels like a private courtroom with only one verdict.

Hathcock did what he always did. He narrowed the world.

Not to be brave. To be functional.

The Shot They Said Couldn’t Be Done

The phrase “1.4-mile shot” sounds like myth if you’ve never studied shooting. It sounds like something someone says at a bar and exaggerates with every retelling.

But distance shooting is not magic. It is math, environmental reading, disciplined technique, and a deep understanding of how a projectile behaves over time. The farther a bullet travels, the more the world has time to interfere with it.

Wind isn’t one thing across a long distance. It’s many winds—different at the shooter’s position, different mid-flight, different near the target. Temperature and humidity affect air density. Light bends perception. The slightest misread becomes huge by the time the bullet arrives.

And in combat, there’s another complication: you’re not firing at a paper target that stays still and politely waits.

You’re firing to remove a threat before it removes someone else.

In the famous story, Hathcock made an extraordinary long-range shot using a heavy machine gun fitted with a scope. The details have been told in multiple ways over the years, but the core idea remains: he used available equipment creatively, pushed beyond what most people believed possible, and delivered a result that changed how others thought about range.

What matters is not the bragging rights. What matters is the mental process behind it.

A person doesn’t make a shot like that by “just trying.” He makes it by understanding exactly what must go right—and then doing the work to make it right.

He would have accounted for distance and drop. He would have watched the environment. He would have read the conditions with the same seriousness he read targets. He would have committed only when the picture made sense.

And then—one shot.

Not a volley. Not repeated attempts that reveal position. Not drama.

Just the decision, the squeeze, and the discipline to let the shot happen cleanly.

That’s why it became legend: it challenged assumptions about what was possible, and it highlighted the difference between confidence and skill.

What Legends Leave Out

Stories about war often flatten complexity. They turn people into characters: hero, villain, rival, prey. But the real weight of a sniper’s life isn’t only in the shots that land. It’s in the hours of watching, the tension of waiting, and the knowledge that every success has consequences that don’t fit neatly into celebration.

Hathcock’s reputation grew, and with it came a strange burden: when people believe you can solve impossible problems, they bring you more impossible problems.

At the same time, the enemy adapts. A skilled opponent watches your patterns and tries to break them. That’s what makes the Cobra story compelling—even if details are debated. It represents the reality that expertise attracts attention, and attention attracts danger.

In the end, the “1.4-mile shot” wasn’t just a technical milestone. It was a symbol of something broader: the way necessity in war forces innovation, and the way calm minds under pressure can reshape what everyone else believes.

But it also leaves a quieter lesson that veterans often understand better than anyone reading from a distance:

Even the most capable people don’t walk away untouched.

They just learn to carry it.

The Human Cost of Precision

A sniper’s work is often described as surgical. That word can be misleading. Surgery is meant to heal. Combat is meant to stop a threat. The technique may be precise, but the moral weight is not clean.

Hathcock’s story endures partly because it isn’t only about skill. It’s about discipline under fear. It’s about carrying responsibility. It’s about the uncomfortable truth that sometimes a person can be both highly effective and deeply human at the same time.

If you strip away the dramatic language, what you find is a man shaped by hardship, refined by repetition, tested in a conflict that demanded more than technique—and remembered because, for a moment, he did something that forced even skeptics to admit:

Some limits aren’t real.

They’re just unchallenged.