The photograph was never meant to stand out.

That was what Rachel Chen told herself the first time she lifted the small leather case from the bottom of a collapsing cardboard box at a Richmond estate sale. The box had been shoved under a folding table, surrounded by chipped china and yellowed ledgers, the kind of forgotten items people no longer wanted to sort through.

Rachel had seen this before. Hundreds of times.

Old photographs. Carefully posed families. Expressions fixed into seriousness by long exposure times and social expectation. Images designed to project stability, success, and permanence—even when none of those things were truly secure.

Still, something made her pause.

She opened the case.

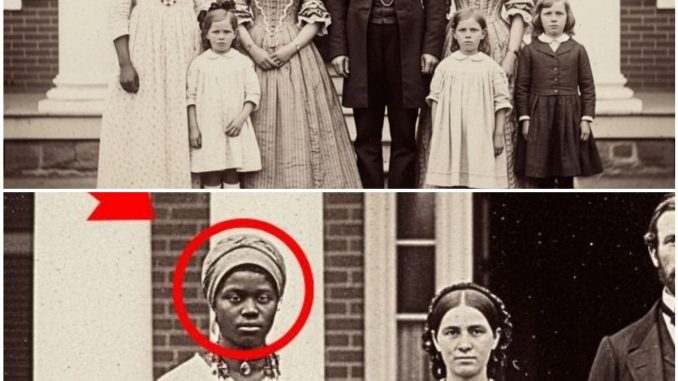

Inside lay a daguerreotype, its surface dulled slightly by time but still intact. The image showed a white family of five standing in front of a brick house with tall columns that rose like declarations of permanence.

A man stood at the center, his jaw set hard, eyes alert as if guarding something unseen. His posture carried authority, the confidence of someone accustomed to being obeyed.

Beside him stood a woman in a tightly structured dress, the fabric expensive, the tailoring precise. Her expression was calm but controlled, the practiced stillness of someone who understood how she was meant to be seen.

Three children stood in front of them, arranged by height. Their hands were folded stiffly, fingers interlaced as adults had instructed. None of them smiled.

It was a composition Rachel knew well.

She had cataloged hundreds of photographs like this during her years working with historical collections. Wealth framed as order. Family presented as proof.

Her fingers hovered over the edge of the case, ready to close it.

Then she noticed the figure behind them.

A young Black woman stood slightly apart, positioned just far enough back to remain clearly visible yet unmistakably secondary. She was not touching the family, not leaning in. Her place was defined with care.

She wore a plain calico dress, practical and unadorned, and a simple head wrap tied close to her scalp. Her posture was straight—too straight, Rachel thought, for someone meant to blend quietly into the background.

Rachel tilted the photograph toward the light.

As the angle shifted, the woman’s face became clearer.

Her eyes were not lowered.

They met the camera directly.

There was no fear in them. No submission. Instead, Rachel sensed something deliberate, an awareness that contradicted the role the image tried to assign her.

Rachel felt the familiar tightening in her chest.

It was a sensation she had learned to trust over more than a decade of working with historical photographs. The feeling that told her an image was holding something back.

She noticed the necklace then.

A thin strand of beads rested just above the collar of the woman’s dress, barely visible unless one looked closely. It could have been dismissed as decorative, accidental, unimportant.

Rachel did not dismiss it.

She bought the photograph without negotiating the price.

Back in Washington, Rachel placed the daguerreotype beneath the high-resolution scanner in the museum’s conservation lab. The room was quiet except for the low hum of machinery and the distant echo of footsteps in the hallway.

As the scan began, Rachel reminded herself to remain cautious. Objects did not always mean what viewers wanted them to mean. Beads could be decorative. Jewelry could be random.

Still, she watched closely as the image sharpened on her screen.

She zoomed in on the woman’s face first.

The detail startled her.

The gaze held steady, intelligent, composed. There was an awareness there that felt intentional, as if the woman understood the moment and chose how to meet it.

Rachel shifted her focus downward.

The necklace resolved into individual beads.

Her breath caught.

They were arranged in a pattern.

Three white beads. Two red. One black. Two red. Three white.

The sequence repeated with exact precision.

Rachel leaned back in her chair, pulse quickening.

She had seen this before.

Not this exact configuration, but the idea behind it.

During her graduate studies, she had researched African-American material culture, particularly the ways enslaved people embedded meaning into objects that enslavers dismissed as insignificant. Patterns were rarely arbitrary. They were language.

Rachel saved the images and sent an email marked urgent.

Dr. Amara Okafor called less than two hours later.

“Rachel,” she said without preamble, “where did you find this?”

“An estate sale in Richmond,” Rachel replied. “The photograph appears to be from around 1860.”

There was a pause on the line, followed by the soft sound of pages turning.

“This pattern,” Dr. Okafor said slowly, “is Yoruba. Very specific Yoruba. The sequence signifies lineage and spiritual protection. It is not decorative. It is communicative.”

Rachel felt a chill move through her.

“So she knew exactly what she was wearing.”

“Yes,” Dr. Okafor replied. “And so would anyone else who recognized it.”

Rachel glanced back at the image glowing on her screen.

“Then she was taking a risk.”

“In Virginia, in 1860?” Dr. Okafor said quietly. “An enormous one.”

After the call ended, Rachel remained in the lab long after the lights dimmed automatically for the evening. The woman in the background of the photograph no longer seemed passive.

She had been speaking.

Identifying the white family proved relatively easy. The house was distinctive, its brickwork and column design common among Richmond’s tobacco elite. Census records confirmed it: Daniel Whitfield, merchant; his wife, Margaret; and their three children.

The enslaved woman was another matter.

The slave schedules listed her only as “mulatto female, age 20.”

No name.

Rachel hit her first wall there.

Days turned into weeks as she searched through church registers, business records, letters, and estate documents. The woman appeared nowhere else, as if she had existed only for the brief moment the camera captured her image.

Late one night, Rachel found a Freedmen’s Bureau registration dated May 1865.

Anney Whitfield.

Age 25.

Formerly enslaved by Daniel Whitfield.

Occupation: seamstress.

One child.

Rachel stared at the entry, reading it again and again.

A name.

Not a category. Not a description.

A person.

The triumph was fleeting. There were no birth records. No death certificate. No indication of what had happened to Anney between 1860 and emancipation.

History revealed just enough to prove itself real, then withdrew.

Then came the email.

The subject line read: I think you found my ancestor.

Diane Washington wrote from Atlanta. Her family, she explained, had passed down stories of a woman named Anney—known as “Mama Anney”—who had been enslaved in Richmond and wore a beaded necklace taught to her by her mother.

The necklace, Diane wrote, had been lost generations earlier. But the pattern had survived in memory.

Rachel called her immediately.

“My grandmother used to say the beads carried protection,” Diane said. “She said Anney wore it even when she was afraid.”

The photograph was no longer silent.

As Rachel and Diane pieced the story together, contradictions emerged. Dates conflicted. Locations overlapped in ways that made no sense.

Then Dr. Okafor raised an unsettling possibility.

“What if Anney wasn’t meant to survive?” she asked.

She explained that certain bead patterns were reserved for specific lineages, sometimes tied to ceremonial or political roles. If Anney wore such a pattern, it suggested her mother had not been an ordinary captive.

Rachel reached out to scholars in Nigeria.

One name appeared repeatedly: a historian specializing in the Oyo Empire.

When he examined the pattern, his response was immediate.

“This design,” he said, “was associated with families connected to the royal court. Not royalty—but close enough to matter.”

If Anney’s mother carried that lineage, then the necklace was not just memory.

It was evidence.

When the museum exhibition opened, visitors arrived in droves. Some stood in silence before the photograph. Others debated the interpretation.

Not all responses were welcoming.

Emails arrived accusing the museum of exaggeration. A private collector claimed ownership of a similar necklace. One anonymous message warned Rachel to “stop rewriting history.”

One evening, Rachel discovered the photograph’s digital file had been corrupted.

Only one element remained intact.

The necklace.

At the final family gathering, Diane held a recreated version of the beads in her hands. Around her stood dozens of descendants, connected by a pattern that had survived captivity, erasure, and time.

The photograph hung nearby, unchanged.

Anney still stood in the background. Still half-hidden. Still looking directly forward.

Rachel wondered what else Anney had known. What warnings she had woven into those beads.

If one necklace could carry this much history, how many other messages were still waiting in photographs no one had examined closely enough?

The image endured.

The pattern remained.

And somewhere between the past and the present, Anney’s voice was still speaking—unfinished, unresolved, and far from done.