Afraid of Freedom

June 8, 1945.

At Camp Gruber, the war had already ended on paper. World War II was over. Germany had surrendered. The announcements had been read, the flags had changed, and the world was beginning to speak the language of “after.”

Fifteen-year-old Klaus Becker stood at the fence anyway.

Not because he wanted to escape.

Not because he wanted to fight.

He stood there because the idea of leaving made his chest tighten in a way he didn’t know how to explain. He wrapped both hands around the chain-link until his knuckles lost their color, staring out at the prairie that seemed to go on forever—flat land, wide sky, nothing burning, no sirens, no collapsing walls.

Behind him, a guard’s boots crunched over gravel. Klaus didn’t turn his head.

He had been there a long time. Long enough for the sun to shift, long enough for his palms to sweat against the metal, long enough for the strangest thought of his life to settle into place:

For the first time, he was afraid of freedom.

Most prisoners begged for release. Most dreamed about the first step outside the wire.

Klaus was bracing for something worse than captivity.

He was bracing to be sent back to Hamburg—back to a city he could no longer picture as real, back to rubble and hunger and a future that smelled like cold ash. His father was gone. His older brother had never come home. His mother, last he’d heard, had vanished into the confusion of shifting borders.

He tried to summon the idea of “home,” and his mind refused to cooperate.

Home was supposed to be a place. What waited across the ocean felt more like a question no one wanted to answer.

Here in Oklahoma, behind wire and watchtowers, there was food. There was routine. There were books. There was school. There was sleep that lasted through the night.

And in a twist Klaus felt ashamed to admit even to himself, the camp had given him something Germany couldn’t promise anymore:

A future.

That realization had struck him three nights earlier, when he lay on his bunk staring at the ceiling of the barracks. He tried to imagine returning to Hamburg—walking streets he knew, finding doors that still opened, calling out for his mother.

Nothing came.

The streets were gone in his mind. The doors were gone. The voice in his head that used to say “it will be okay” had stopped showing up.

What waited for him wasn’t a return.

It was a restart, and Klaus didn’t know if he had anything left to restart with.

Hitler’s Children

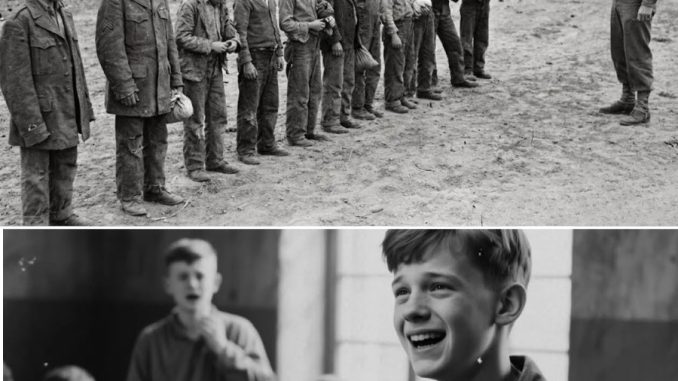

The boys had arrived at Camp Gruber in the winter of 1945.

Some Americans called them “Hitler’s children,” a phrase that sounded like both accusation and pity. Most were thirteen to sixteen—faces still soft, shoulders still narrow, uniforms that didn’t fit right. Helmets sat too low. Belts had to be tightened until the leather folded.

They had been pulled into the war late, when Germany was running out of men and time. Some had been attached to the Wehrmacht. Others had been forced into the Volkssturm—the desperate last line of defense made from boys and old men.

A few had been present near Battle of the Bulge. Others had dug trenches, carried messages, or stood beside anti-aircraft guns they could barely operate.

When American troops captured them, many looked less like enemy soldiers and more like children in costumes no one had asked them if they wanted to wear.

The U.S. Army didn’t know what to do with them.

They weren’t the kind of prisoners you could treat as hardened fighters. They were kids.

But they also couldn’t simply be sent back immediately. Many had nowhere to go. Many had no clear family. And a shattered country doesn’t always welcome its youngest survivors with open arms.

So they were shipped to camps across the American heartland—places that sounded unreal to German ears, names the boys repeated like nonsense syllables until they began to feel like geography: Texas, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma.

Camp Gruber, near Muskogee, became one of the largest holding sites for them.

They lived in wooden barracks. Ate in mess halls. Stood for roll call. Followed rules. And then, slowly—almost quietly—something unexpected began to happen.

They started to heal.

Not dramatically. Not in speeches.

In the small way healing happens when nobody is shouting in your face, when nights are quiet, when meals arrive regularly, when the future is a day-by-day thing you can hold without dropping.

Klaus Before Oklahoma

Klaus had been taken in December 1944.

Fourteen years old.

His father, a factory foreman, had been killed in an air raid the year before. His older brother was gone too, swallowed by a front Klaus only knew through fragments of letters and a silence that never lifted.

When men arrived with orders and uniforms and a certainty Klaus didn’t have, his mother begged them to leave her last son alone.

They took him anyway.

They pressed a rifle into his hands and told him to defend something called the fatherland—an idea that sounded grand until you were the one being sent to stand in the cold for it.

Klaus did not fire a shot in anger.

His unit surrendered to American forces near Aachen in February 1945. The soldiers who captured them looked confused more than furious, as if they couldn’t quite process what they were seeing.

One American—young enough that Klaus could imagine him as a classmate in a different world—offered Klaus a cigarette.

Klaus didn’t smoke. He took it anyway.

It was the first kindness he’d received in months.

The journey to America took weeks. The boys crossed the Atlantic packed in tight spaces, sea-sick and anxious, pretending bravado and then falling quiet when nobody was watching.

They talked about escape the way teenagers talk about impossible plans—part fantasy, part fear disguised as confidence.

But when they arrived and stepped into the stillness of the prairie, something inside them changed.

There were no broken buildings. No nightly sirens. No smoke hanging in the air.

The guards were firm, but the cruelty Klaus expected never arrived.

The food was plain, but there was enough of it.

And for the first time in years, boys who had been treated like tools were allowed, in small ways, to be boys again.

“Treat Them Like Kids, Not Like Enemies”

The camp commander, Colonel William Hastings, did something that shaped everything that followed.

He gathered his officers and gave them a simple order:

Treat them like kids, not like enemies.

Some guards didn’t like it. Many had lost brothers and friends. Mercy felt like betrayal.

Hastings didn’t argue with grief. He simply refused to let grief become policy.

“These kids didn’t start the war,” he told them. “And they won’t end it by rotting in a camp. Teach them. Give them a chance to become something else.”

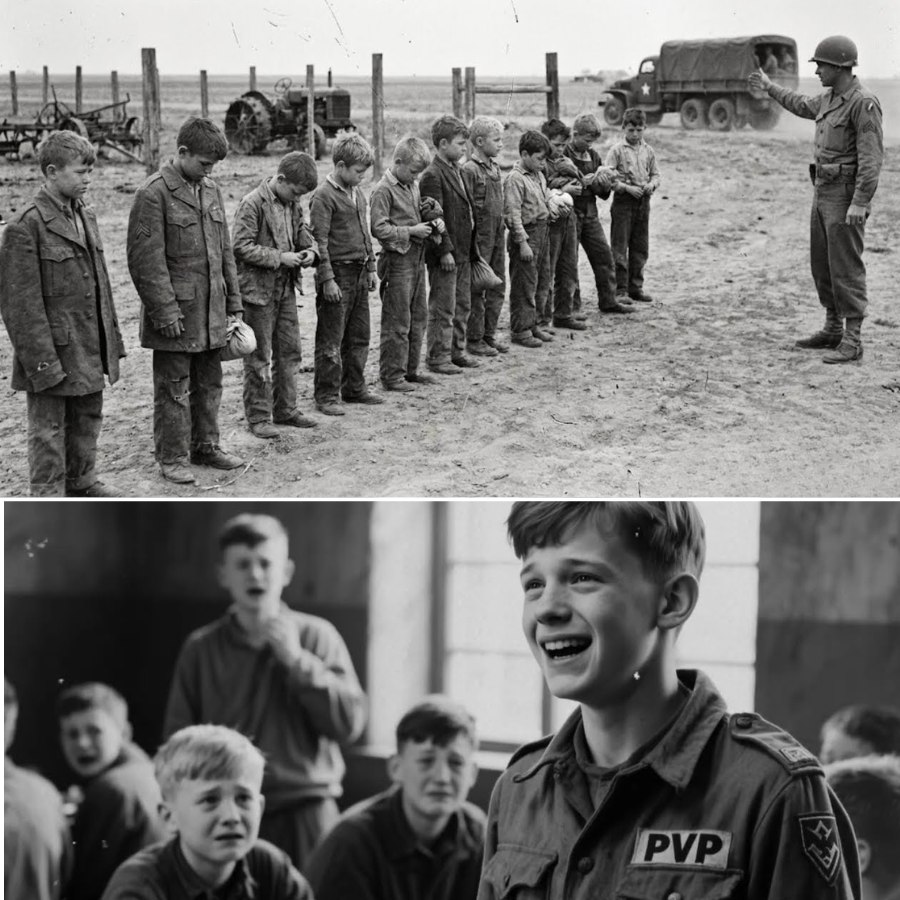

So they built a school.

A German immigrant and former professor, Dr. Friedrich Lang, was brought in to run it. He taught math, history, English—and something the boys had rarely been encouraged to practice before:

Thinking for themselves.

He asked questions instead of demanding slogans. He made them discuss, argue, read. He brought newspapers from multiple sources and made them compare what was said, what was omitted, and why.

At first, the boys resisted. They had been trained to treat doubt like weakness.

Klaus remembered a day when Dr. Lang spoke about the camps in Europe where civilians had been targeted and killed on a massive scale. Klaus stood up and called it propaganda. He said it loudly, partly because he believed it, and partly because admitting uncertainty felt like stepping off a cliff.

Dr. Lang didn’t shout him down.

He looked at Klaus with something close to sorrow.

“I understand why you want it to be false,” he said quietly. “But the truth doesn’t care what we prefer.”

That night Klaus couldn’t sleep.

He thought about his father’s stories of pride and glory and destiny—and he wondered how much of it had been designed to keep boys like him obedient.

The Routine That Felt Like Life

By spring, Camp Gruber had a rhythm.

Wake early. Chores. Classes. Meals. Recreation.

The boys played soccer on a dirt field behind the barracks. They borrowed books from a small library. Klaus spent hours there, drawn to stories about distance and reinvention.

He discovered Mark Twain and Jack London and began to imagine a life where the world was not defined by uniforms and orders.

Then May 8 arrived.

The announcement came over the loudspeakers: Germany had surrendered unconditionally.

The boys crowded into the mess hall. Some cried. Some stared at the floor. One boy—sixteen, named Hans—let out a cheer before catching himself, as if relief was something he wasn’t sure he was allowed to feel.

After that, uncertainty spread through the camp like a slow fog.

Would they be shipped to Europe immediately?

Would they be punished?

Would they be kept?

Rumors multiplied. No one knew which ones were true.

Klaus began dreading the day he’d be put on a ship back to Germany.

He tried to picture walking through Hamburg, searching for his mother, living among ruins, rebuilding a life in a place that might look at him and only see guilt.

And the more he pictured it, the more his stomach turned.

One evening he went to Dr. Lang.

“What if I don’t want to leave?” Klaus asked, voice low.

Dr. Lang studied him carefully.

“You’re a prisoner of war,” he said. “You don’t get to choose.”

“But the war is over,” Klaus insisted.

“Yes,” Dr. Lang replied. “And now your country has to rebuild. That work needs young people too.”

Klaus shook his head.

“There’s nothing to rebuild. My home is gone. My family is gone. What am I going back for?”

Dr. Lang didn’t answer immediately. He looked out at the prairie.

“I asked myself a similar question years ago,” he said softly. “And I chose to leave.”

Then he turned back.

“But you’re fifteen, Klaus. Don’t run because it’s broken. If you can, help fix it.”

Klaus wanted to believe him.

But belief is difficult when your future looks like smoke.

“I Don’t Belong Anywhere”

By June, dozens of boys had told someone—guards, teachers, chaplains—that they wanted to stay in America.

Some wanted to finish school. Some hoped to work. Some simply couldn’t face what awaited across the ocean.

The authorities were baffled. Rules and conventions assumed adult soldiers, not children who had been pulled into war at the end and then held in a place that, strangely, began to feel safer than the world outside.

Still, orders came down.

Repatriation would begin within weeks.

Klaus heard the schedule and felt something inside him give way—not a dramatic break, just a quiet collapse.

That night he lay awake staring at the ceiling, thinking about running, hiding, disappearing.

Then he realized how pointless it was.

The next morning he returned to the fence and stood there again, hands gripping the wire, eyes fixed on the open land beyond.

A guard—Corporal Miller—walked up beside him.

“You okay, kid?” he asked.

Klaus didn’t answer at first.

“I know it’s hard,” Miller said. “But you’ll be alright. Germany’s going to need people your age.”

Klaus turned slightly, looking up at him.

“What if I don’t want to go?”

Miller hesitated, as if searching for the correct official response.

“Doesn’t matter what you want,” he said finally. “It’s what has to happen.”

“Why?” Klaus asked.

Miller’s face tightened.

“Because that’s where you belong.”

Klaus shook his head once, slowly.

“I don’t belong anywhere.”

And that was the truth beneath everything.

Not ideology. Not politics.

Belonging.

A teenager who had been used up by a collapsing regime, who had seen his city disappear, whose family had scattered, standing behind a fence in Oklahoma and realizing the only place that felt steady was the place he wasn’t allowed to choose.

The prairie didn’t answer him.

It simply stretched on—wide, quiet, indifferent, and free.

And Klaus stood there, afraid of the freedom he could see but could not keep.

If you want, send Part 2 from your source as well (or say “continue from here”), and I’ll rewrite it in the same tone and length, keeping it AdSense-safe and consistent.