The account book lay open on the mahogany desk like a scar that time refused to heal. Fresh ink still shimmered where a clerk’s pen had lingered too long—names aligned with figures, dates pressed into columns that pretended to be orderly. Each line looked harmless on its own. Together, they told a story no one in the house was meant to read.

Beyond the tall windows, Charleston breathed through a humid afternoon. The river moved slowly, weighted with cargo and heat, while ships eased toward their berths with the patience of creatures that had learned not to hurry. Outside, the world continued as it always had. Inside the Whitcombe residence on East Bay Street, something had shifted, and it would not settle again.

On the morning Margaret Whitcombe turned fourteen, her father presented her with what he called a practical gift.

It was not silk from France. Not a new volume of poetry. Not the piano lessons she had been begging for since spring. Instead, it arrived quietly, without ceremony, in the form of a girl.

The carriage stopped short of the front steps, as though the horses themselves sensed the impropriety. The driver did not knock. He waited.

The door opened anyway.

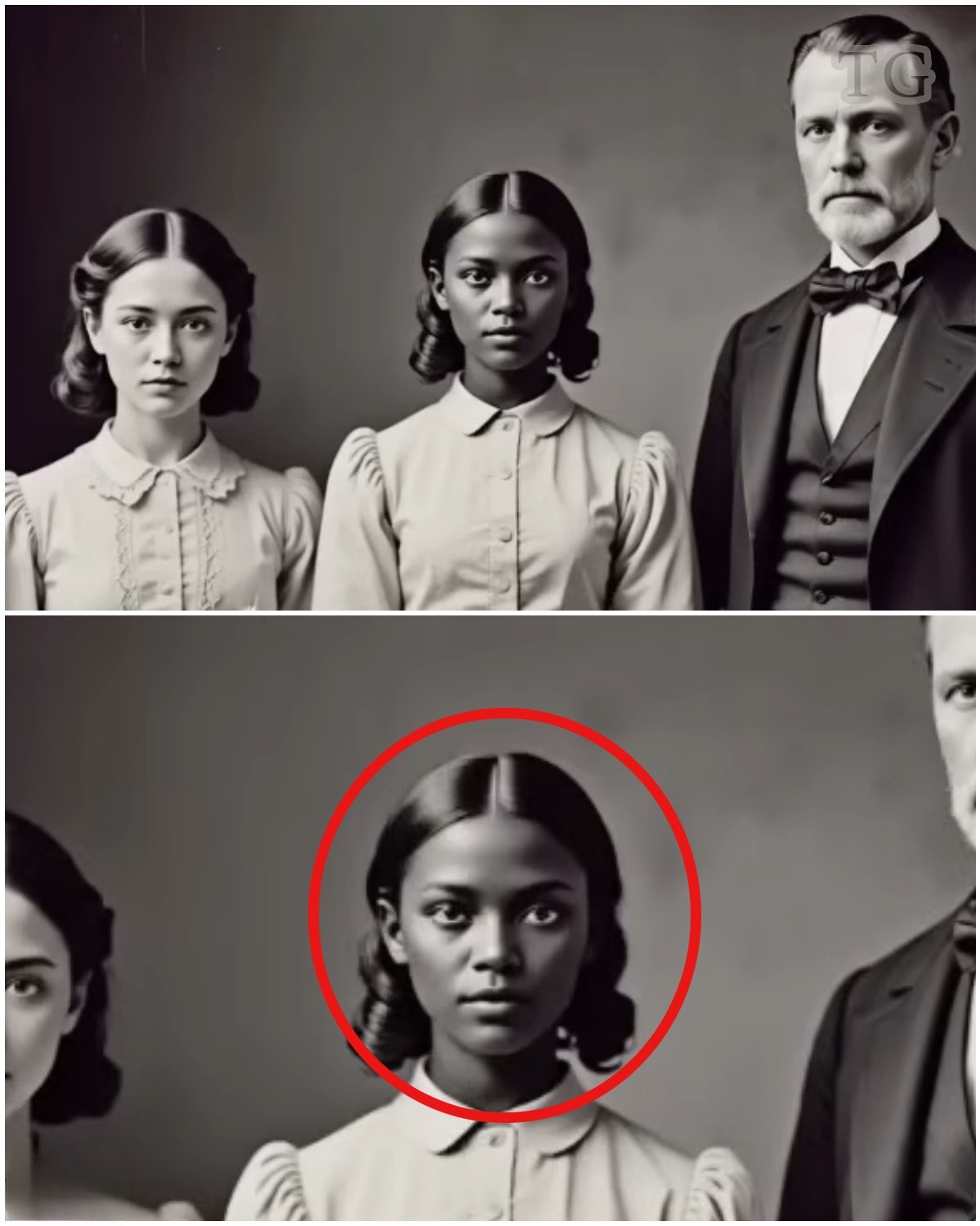

The girl stepped down alone. Her posture was careful, practiced. She wore a plain dress, clean but undecorated, the sort meant to disappear into the background of larger rooms. Her hands were folded in front of her body, fingers pressed together as if holding herself intact. She did not lift her eyes.

Her name, the driver said softly, was Eliza.

Nothing about her should have caused alarm. Nothing, except the moment she crossed the threshold.

Sound drained from the entrance hall. Servants froze mid-step, trays held suspended as if the air itself had thickened. Mrs. Whitcombe’s fingers tightened around the banister until her knuckles blanched. Margaret, who had been descending the staircase two steps at a time, stopped halfway down and stared.

It was not resemblance.

It was duplication.

The angle of Eliza’s face, the slight cleft in her chin, the shape of her mouth when held in stillness—these were not echoes or coincidences. They belonged to someone Margaret knew. Someone she had seen only in paint and memory.

Her father.

In the study hung a portrait of Edmund Whitcombe as a boy, preserved in oil and gilt frame. It was not similar. It was the same face.

“Why does she look like Father?” Margaret asked.

No one answered.

Somewhere in the house, a clock began to tick, each second louder than the last.

Edmund Whitcombe arrived moments later, summoned by a servant whose words had broken apart before forming sense. He took in the scene in a single glance—the frozen staircase, his wife’s pallor, the girl standing at the center of the hall like an unspoken accusation.

He smiled.

“There you are,” he said mildly. “Eliza, was it? You’ll have your duties explained shortly.”

He did not study her face. Not for more than a heartbeat. He did not look toward the study that afternoon. When his wife asked him later whether he had noticed anything unusual, he kissed her forehead and said, “Children imagine patterns where none exist.”

But patterns, once formed, do not dissolve simply because someone refuses to acknowledge them.

Eliza was assigned to the third floor, among rooms that had not known regular use in years. She rose before dawn and lay down long after the house had gone quiet. She learned quickly, worked silently, and never complained.

She watched.

And when she spoke, it was only when addressed—except with Margaret.

Margaret understood she was not meant to grow close to her. The knowledge made no difference. Curiosity settled into something sharper, something that pressed against the inside of her thoughts. She sought Eliza out in the narrow spaces of the house—behind linen doors, beside the back staircase, in the pause between chores.

Eliza spoke of her mother, who sang softly in the evenings. Of a modest house near the river that smelled of ink and citrus. Of a man who visited only after dark and never stayed until morning.

“What was his name?” Margaret asked once.

Eliza shook her head. “He never told me.”

Unease replaced certainty. Margaret began to notice absences she had never questioned before—her father’s unexplained departures, her mother’s careful avoidance of the third floor, the locked door at the end of the corridor that was always clean, never dusty.

The first ledger appeared by chance.

Margaret had been sent to fetch a book from her father’s study. The shelves were immaculate. The desk arranged with obsessive care. Only the drawer betrayed him—sticking briefly before opening too easily.

Inside lay a slim volume, its pages crowded with entries in a careful, deliberate hand. Payments. Locations. Initials. Names that repeated across years, spaced apart yet bound by an unmistakable rhythm.

Margaret read until the words blurred. She returned the ledger exactly as she had found it.

That night, she dreamed of ink bleeding through white linen, soaking layer after layer until it reached skin.

The second discovery was deliberate.

Eliza came to her door just before dawn. Her eyes were wide but steady. “You should see something,” she said. “Before he notices.”

They crept to the third floor. Eliza produced a small key from beneath her sleeve, warm from her palm. The lock opened with a sound like a breath released.

Inside, trunks lined the walls. Letters lay bundled with twine. A single lamp burned low, its oil fresh.

They read until their legs ached.

The letters were written in Edmund’s hand—affectionate, precise. Promises. Apologies. Instructions. A name appeared again and again, crossed out, rewritten, disguised by initials. Beneath it all ran a repeating sequence: visit, gift, silence.

“He paid for me twice,” Eliza said quietly. “Once to my mother. Once to this house.”

Margaret searched for denial. None came.

“He wanted me close,” Eliza continued. “Close enough to watch.”

Fire revealed what words could not.

A small blaze broke out in the kitchen one night, contained quickly but not before smoke filled the lower floors. In the confusion, a trunk vanished from the third floor. Edmund accused a servant and dismissed him without hesitation.

Eliza said nothing.

Days later, the trunk reappeared in the carriage house, its lock broken. Inside lay a single object—the childhood portrait from the study. The canvas had been slashed, the face destroyed beyond recognition.

Edmund’s rage shook the house. He questioned everyone. When he reached Eliza, he stopped himself. Smoothed his coat. Dismissed her with a nod.

The restraint spoke louder than fury.

Margaret confronted her mother that night. Mrs. Whitcombe wept without denial. She spoke of rumors ignored, letters burned, and a quiet bargain made in the name of survival.

“Men do things,” she said hollowly. “And houses endure.”

But houses remember.

The final ledger surfaced on the eve of a grand gala meant to secure Edmund Whitcombe’s standing among Charleston’s most respected men. Margaret found it hidden behind a false drawer back she herself had once repaired. This ledger named names. It traced lines between households, fortunes, and carefully managed disappearances.

To reveal it would destroy her family. To hide it would make her complicit.

Eliza offered another path.

“We leave,” she said. “Tonight.”

They packed lightly, taking only what could be carried. They avoided the main staircase. In the carriage house, Edmund waited.

He looked smaller than Margaret remembered. Older.

“I did what was necessary,” he said.

“For whom?” Margaret asked.

“For order,” he replied.

Eliza stepped forward and met his gaze. The resemblance was unbearable.

They left before dawn.

Weeks later, whispers spread. A ledger burned. A gala canceled. Edmund withdrew from public life, citing illness. The third-floor door remained locked.

Margaret and Eliza reached a city upriver where names softened and faces blended. They lived above a print shop that smelled of ink and citrus. Eliza learned to set type. Margaret learned to listen.

One evening, a package arrived with no return address. Inside lay a single page torn from a ledger.

At the bottom, written in a familiar hand, were the words:

Paid in full.

The ink was still wet.