The summer of 1847 arrived in Louisiana like a fever—thick, suffocating, and impossible to escape. The air hung heavy with the scent of magnolia and damp earth, a sweetness that seemed to hide something darker beneath. In the parish of St. Helena, where cotton fields stretched endlessly toward horizons that offered no mercy, the Bowmont estate rose like a monument to power itself.

Governor Charles Bowmont owned everything the eye could see. Twenty thousand acres, three hundred people held in forced labor, and a wife whose beauty was discussed in parlors from Baton Rouge to New Orleans. Elellanena Bowmont was a vision rendered in silk and pearls, her blonde hair always perfectly arranged, her posture a study in aristocratic grace.

At thirty-two, she had mastered the art of being admired without being known, praised without being understood. But beneath the corsets and courtesy—beneath the practiced smiles and Sunday prayers—Elellanena Bowmont was suffocating. The mansion itself was a cathedral of southern excess: white columns that reached toward God, marble floors imported from Italy, chandeliers that caught the light like frozen waterfalls, twelve bedrooms, though only one was ever meant to hold husband and wife.

Separate wings, separate lives, separate worlds under the same roof. Charles Bowmont was fifty-seven, a man whose face had been shaped by ambition and hardened by power. His political career had been built on cotton, compromise, and the calculated subjugation of those he deemed beneath him. He spoke of civilization and progress, while his wealth was paid for by people who picked his fields under the Louisiana sun, day after day, year after year.

He loved his wife the way he loved his plantation: as possession, as reflection, as proof of his dominion over the world. Elellanena knew her place in that arrangement. She had known it since the day her father traded her future for political favor when she was seventeen. Marriage was not romance, but transaction—not partnership, but performance.

She played her role with precision: the gracious hostess, the devoted wife, the symbol of refinement every governor needed on his arm—until the day she saw Elijah. Tell me in the comments which country you are from and what you thought of this story and if this story made an impression on you. Subscribe to the channel so you don’t miss any future stories.

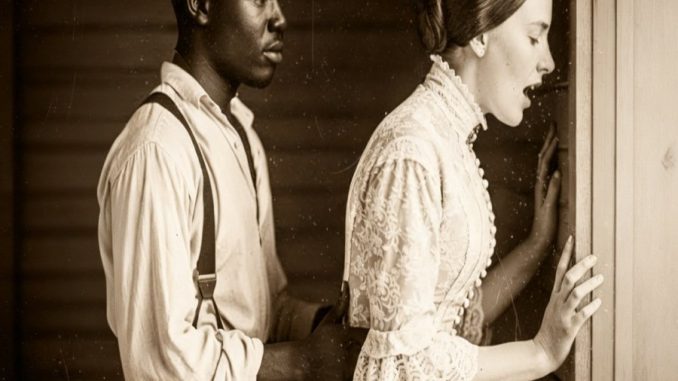

It happened in the stables on a morning in late May, when the heat had not yet become unbearable and the world still pretended at gentleness. Elellanena had come to inspect the new mare Charles had purchased—another acquisition, another display of wealth. She rarely ventured to the working parts of the estate. Her world was confined to gardens, parlors, and the suffocating propriety of afternoon tea.

But that morning, drawn by a restlessness she could not name, she walked past the rose garden, past the quarters where the house workers lived, toward the stables where field hands sometimes came for repairs and supplies. He was shoeing a horse when she entered.

Elijah was thirty years old, though the record books listed him as property item number 47—acquired in 1839 for eight hundred dollars.

He stood six feet tall, his body shaped by labor that would have broken lesser men, his skin dark as Louisiana earth after rain. But it was his eyes that stopped Elellanena in her tracks—eyes that did not drop, did not shrink, did not perform the submission that the system demanded.

He looked at her for three seconds that stretched into eternity. Then he returned to his work. Elellanena felt something crack open inside her chest, something she had sealed away so thoroughly she had forgotten it existed. She stood there frozen, watching the way his hands moved with precision and care, the way he spoke softly to the horse in a voice that carried no panic, no pleading—only a quiet steadiness that seemed impossible in a world designed to grind it out of people.

“You,” she said, her voice barely audible. “What is your name?”

He did not look up. “Elijah, ma’am.”

“Elijah,” she repeated, and the name felt like prayer and violation all at once.

She left without another word, her heart thundering against her ribs, her hands trembling inside her lace gloves. That night, she could not eat. She could not sleep.

She lay beside her husband’s snoring form and stared at the ceiling, seeing nothing but those eyes—eyes that refused to be reduced, refused to vanish, refused to become nothing.

It should have ended there. In any reasonable world, in any story with sense and safety, Elellanena Bowmont would have returned to her needlework and her social calls, and Elijah would have remained what the law declared him to be: a thing, not a person—certainly not a man who could matter.

But the heart does not obey the law, and some hungers, once awakened, cannot be forced back into silence.

The second time they spoke was in the rose garden three days later. Elellanena had taken to walking there in the early morning before the house stirred, before the performance of her life began. She told herself she needed air, needed solitude—needed anything but the truth clawing its way to the surface.

Elijah was pruning the roses. His presence there was not unusual. The people forced to labor for the Bowmont estate were everywhere and nowhere—visible only when needed, invisible when inconvenient. But Elellanena knew, the way guilt and longing always know, that he had been placed there deliberately; that someone—perhaps the overseer, perhaps fate itself—had brought them close again.

“They’re beautiful,” she said, gesturing toward the roses.

“Yes, ma’am.” His voice was careful, neutral, empty of anything that could be used against him.

“Do you have a family, Elijah?”

The question hung in the humid air like something dangerous. Enslaved people were not supposed to have families—not in any way protected by law or sentiment.

They had connections that could be severed at auction, bonds that existed only until they became inconvenient to someone else’s profit.

“Had a wife once,” he said quietly, his hands never stopping their work. “Sold off seven years back. Alabama, I heard. A daughter, too. Never knew what happened to her.”

Elellanena’s throat tightened.

She had heard such stories before. Everyone had. They were the background noise of southern life, the acceptable tragedies that allowed people like her to sleep in silk sheets while others slept under the weight of ownership. But hearing it from his lips, seeing the grief that lived in the set of his shoulders, made it real in a way that shattered something fundamental inside her.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

He looked at her then—truly looked at her—and she saw something flicker across his face. Not hope, which would have been reckless. Not trust, which would have been impossible. But recognition, perhaps—the acknowledgment that she had spoken to him as if he were human, as if his loss mattered, as if his pain was not merely the natural order of things.

“Sorrow don’t change nothing, ma’am,” he said. “But I thank you for it anyway.”

She wanted to say more. She wanted to rage against the injustice, to promise things she had no power to deliver, to somehow erase the chasm of cruelty between them. But the words died in her throat, because what could she say that would not be shameful in its inadequacy?

Instead, she did something far more dangerous.

She came back the next morning, and the morning after that. At first, they barely spoke. Elellanena would walk among the roses while Elijah tended them, the silence between them heavy with things that could not be said. But gradually—carefully—words began to emerge. Small exchanges that meant nothing and everything.

She asked about the roses, and he taught her their names, their needs, the patience required to make beauty bloom in hostile soil. He spoke of seasons and pruning, of knowing when to cut back and when to let grow, and she heard in his words a metaphor for survival that made her chest ache. She told him about books she had read, about the world beyond Louisiana that she would never see, about the suffocating emptiness of a life lived entirely for appearance.

She did not tell him she was lonely. That would have been too naked, too honest. But he heard it anyway—in the pauses between her words, in the way her voice softened when she forgot to perform.

The house workers noticed first. They always did. People survived by paying attention, by reading subtleties that the powerful believed were invisible.

They saw Elellanena Bowmont rising before dawn, saw her walking to the rose garden with increasing frequency, saw the way she lingered when Elijah was there and left quickly when he was not. Mama Saraphene, the cook who had served the Bowmont family for thirty-four years, watched with eyes that had seen too much to be surprised by anything.

She said nothing, but she began leaving biscuits wrapped in cloth near the garden gate—a small kindness, a silent warning, a prayer against the storm she knew was coming.

Because everyone knew what happened when white women looked at Black men with anything other than indifference or contempt. Everyone knew the stories of accusations, of mobs, of bodies found after the night had done its work, of communities destroyed because someone smiled too warmly or stood too close.

But Elellanena and Elijah were not smiling.

They were drowning—separately and together—in something neither of them had permission to feel.

By the end of June, they were talking about things that mattered. She told him about her marriage—not in complaint, which would have been improper, but in careful confession: the loneliness, the sense of being a decoration rather than a person, the slow suffocation of living a life chosen by others.

He told her about freedom—not as a place, but as a feeling he remembered from childhood before he had been sold for the first time at age eight. The memory of his mother’s voice. The taste of food he had grown himself. The brief shining moments when he had belonged to himself.

They never touched. Not once.

They maintained the physical distance that law and custom demanded, but in every other way they were reaching toward each other across an abyss that was supposed to be uncrossable.

And in the mansion, Governor Charles Bowmont began to notice that his wife was smiling again.

He did not know why, and that made him uneasy.

A man of his position understood power, control, the careful maintenance of order. A content wife was desirable. But a wife with secrets was dangerous.

He began to watch.

And in the quarters, people began to pray.

July arrived with a vengeance that seemed almost biblical. The sun pressed down on Louisiana like judgment, turning the air into something visible, something that had to be pushed through with effort. The cotton fields shimmered with heat waves, and the workers moved through them like ghosts, their bodies mechanical with exhaustion, their minds fleeing to whatever interior spaces still belonged to them alone.

Inside the Bowmont mansion, Elellanena felt the heat in a different way—as fever, as recklessness, as the physical manifestation of what was growing inside her chest.

She had stopped pretending—at least to herself—that her morning walks were about roses or fresh air or any of the acceptable reasons a woman of her station might leave her bed before dawn.

She went to see him.

That was the truth. Simple, terrible, undeniable.

Elijah had been reassigned to work closer to the main house. The overseer—a man named Thaddius Cole, whose cruelty was notorious even by the standards of a system built on cruelty—had made the change without explanation.

Some whispered Cole suspected something, that he was positioning Elijah where he could be watched more closely. Others thought it was coincidence, the constant reshuffling of human property that happened on plantations.

But Mama Saraphene knew better.

She had seen the way Governor Bowmont’s eyes had begun to track his wife’s movements, had heard him asking casual questions about Eleanor’s habits, her routines, her unexplained cheerfulness.

“The governor not a fool,” Saraphene said to Elellanena one morning, catching her in the hallway before she could slip outside. “He patient. He calculating. And he caught the scent of something wrong.”

“Child,” Saraphene said, her voice low, “you playing with fire that going to burn more than just you.”

Elellanena stopped, her hand on the doorframe.

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Yes, you do.” The old woman’s voice was not unkind, but it carried the weight of someone who had watched this story before, who knew how it ended. “I seen the way you look when you come back from them morning walks. I seen the way that man look when you pass by. And I’m telling you now, ain’t nothing good going to come from this.”

“We’ve done nothing wrong,” Elellanena said, and heard the desperation in her own voice.

“Don’t matter what you done or ain’t done. Matters what it look like. Matters what the governor going to think when he find out. And he will find out, Miss Eleanor. He always do.”

Elellanena met the old woman’s eyes and saw genuine fear there—not for Elellanena’s reputation or marriage, but for Elijah’s life.

That was what transgression meant in this world.

For her, it might mean scandal, separation, social exile.

For him, it meant a punishment so brutal it would be used as a warning for generations.

“I’ll be careful,” Elellanena whispered.

“Careful ain’t enough,” Saraphene replied. “You need to stop now before it too late.”

But it was already too late, and both women knew it.

That afternoon, Elellanena found Elijah in the workshed behind the stables, repairing a broken wagon wheel. The space was dim and close, smelling of wood shavings and oil, and for the first time since their encounters began, they were truly alone.

No garden paths where servants might pass. No open spaces visible from the house.

“You shouldn’t be here,” Elijah said without looking up, his hands steady on the spoke he was fitting into place. “I know they watching now. Cole been asking questions. Where I go, what I do, who I talk to.”

“I know,” Elellanena repeated, and this time her voice broke slightly.

Elijah set down his tools and finally looked at her. In the shadowed interior of the workshed, his face was half hidden, but his eyes caught what little light filtered through the cracks in the walls.

“Then why you here?”

She could not answer. How could she explain that she had spent fifteen years of marriage feeling like a porcelain figure in a glass case—beautiful and brittle and lifeless—until three months ago, when a man who was not supposed to be seen as a man had looked at her like she was real?

How could she articulate that for the first time in her adult life she felt heard, known—not as an ornament or a duty, but as a person with thoughts and longings and a soul that was starving?

“Because I can’t stay away,” she said finally, and the honesty of it hung between them like something sacred and forbidden all at once.

Elijah was quiet for a long moment. Then he spoke, his voice low and careful.

“You know what they do to men like me who even get accused of looking wrong at women like you? Don’t matter if it true or not. Don’t matter if she the one who come to him.” He stopped, jaw tightening. “You understand what I’m saying?”

“Yes.”

“Then you understand I can’t want this. Can’t let myself want this. Wanting things ain’t for people like me. It just a way to die sooner.”

Elellanena took a step closer, then another. She was trembling from fear or longing or the collision of both. She could not tell.

“What if I wanted enough for both of us?”

“That ain’t how the world work, Miss Elellanena.”

“My name is Elellanena. Just Ellanena. When we’re alone, please don’t call me Miss anything. Let me be just a woman. Just once. Just here.”

Something shifted in his expression—then cracked, like armor under strain.

“You asking me to forget everything that keep me alive. Everything I learned since I was old enough to understand my life don’t belong to me.”

“I’m asking you to remember you’re human. That I’m human. That this”—she gestured between them—“this feeling, whatever it is, it’s real. It matters. Even if the world says it doesn’t, even if the world says we don’t.”

Elijah looked at her for a long time, and she saw the war playing out across his face—between survival and the desperate human need to be seen, to be valued, to matter to someone in a world that had spent his entire life telling him he was nothing.

Finally, he spoke.

“My daughter name was Grace. I think about her every day. Wonder if she remember me. Wonder if she alive. Wonder if she growing up thinking her daddy just left her. Didn’t fight for her. Didn’t love her enough to.” His voice caught. “I couldn’t save her. Couldn’t save my wife. Couldn’t save myself. I wake up every morning in chains I can’t see, but I feel in every breath I take. And you standing here asking me to feel something. To want something. To be something other than what they made me. You know how much that hurt?”

Elellanena felt tears streaming down her face. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I should never have—”

“I didn’t say stop.”

The words fell between them like a spark into dry grass.

“I didn’t say I don’t feel it,” Elijah continued, his voice rough with emotion he had spent a lifetime burying. “I didn’t say I don’t see you every time I close my eyes. Don’t hear your voice when I try to sleep. Don’t wake up thinking about the way you really listen when I talk. Like my words got worth. I just said it hurt. But maybe…” He paused, something desperate and reckless flickering across his face. “Maybe something’s worth the hurt.”

Elellanena closed the distance between them. Her hands reached for his before she could stop herself.

His hands were rough with calluses—marked by labor and a lifetime of being treated like a tool.

Hers were soft, pampered, decorated with rings that cost more than a human life in the economy that had made them both.

When their fingers intertwined, it felt like revolution and ruin all at once.

They stood like that for minutes that felt like hours—barely breathing, not speaking, just holding on to each other across a divide that was supposed to be absolute.

Elellanena could feel his pulse through his palm. Could feel the tremor in his hands that matched the trembling in her own.

“This is madness,” she whispered.

“Yes.”

“They’ll destroy you if they find out.”

“Yes.”

“I can’t protect you. I have no power. I’m just—”

“You ain’t just anything,” Elijah interrupted, and his voice carried a fierceness that made her look up into his eyes. “You a person who see me as a person in this whole world. That rare. That precious. To be seen. Really seen. You know how long it been since I felt that?”

“Then see me too,” Ellanena said. “Please see me. Not the governor’s wife. Not the proper lady. Not the role I have to be for everyone else. Just me. The person I was before they told me who I had to become.”

“I see you, Elellanena,” he said, and hearing her name from his lips—just her name, without title or distance—felt like stepping into something new and terrifying. “I been seeing you since that first day in the stables. Seeing the loneliness you carry like I carry mine. Seeing the cage you in, even though yours got silk bars instead of iron. Seeing the way you hungry for something real.”

“What are we doing?” Elellanena asked, and she wasn’t sure if she meant this moment or the larger arc of what they had set in motion.

“I don’t know,” Elijah admitted. “But I know I’m tired of surviving without living. Tired of being empty inside just to keep breathing outside. If this the only time I get to feel human, to feel wanted, to feel like I matter to somebody—even if it only last a minute—even if it cost me everything—maybe that worth it.”

They were still holding hands when they heard footsteps approaching the workshed.

They broke apart instantly—muscle memory and fear moving faster than thought.

Elijah grabbed his tools. Elellanena smoothed her dress, and by the time Thaddius Cole appeared in the doorway, they were six feet apart: a perfectly proper distance between mistress and enslaved man. Nothing to see but a woman who had wandered into the wrong building, and a man focused entirely on his work.

But Cole was not naive.

His eyes moved between them with the assessing calculation of a man who made his living reading fear.

He was forty-three, lean and weathered, with a face that seemed carved from something harder than flesh. He carried a leather strap coiled at his belt, more as symbol than instrument. Everyone knew what he was capable of, and most days the threat was enough.

“Afternoon, Mrs. Bowmont,” he said, his voice carrying a false politeness that somehow made it worse. “Can I help you find something?”

“I was looking for the stable master,” Elellanena said, her voice steady despite the thunder of her heart. “My mare has been favoring her left foreleg.”

“Stable master in the south barn.” Cole’s eyes flicked briefly to Elijah. “Ma’am, this here just the workshed. Nothing of interest to a lady.”

“Of course. My apologies.”

Elellanena moved toward the door, forcing herself to walk slowly, to maintain the dignity expected of her station. As she passed Cole, she felt his eyes on her like a physical touch—measuring, calculating, storing.

She did not look back at Elijah.

But that night, lying in her bed while her husband slept in his separate chamber, Elellanena stared at the ceiling and felt the echo of Elijah’s hand in hers.

She understood now what she had done—what they had done together.

They had crossed a line that could never be uncrossed.

They had felt something that made them both vulnerable in ways that could get them both destroyed.

And she knew—with the clarity that comes from standing on the edge of an abyss—that she could not stop, would not stop; that whatever this was—love, madness, the desperate rebellion of two caged souls—it had become more necessary than safety, more vital than survival.

In the quarters, Elijah lay on his pallet and touched his palm where her hand had been, trying to memorize the feeling before the world took it away.

He knew what was coming. He had always known. Men like him did not get happy endings. They got punishment. They got erased. They got turned into warnings.

But for a moment in that workshed, he had been fully alive. He had been seen. He had mattered.

And if that was all he ever got, he thought maybe that was enough to risk everything for.

Mama Saraphene, unable to sleep, sat by her window and watched the main house. She had seen this story before generations ago when she was young—a white woman and a Black man forgetting what the world demanded of them.

It had ended in suffering then.

It would end in suffering now.

She began to pray, though she wasn’t sure what she was praying for—salvation or mercy, justice or endurance, forgiveness, or simply the strength to survive what was coming.

Because something was coming.

She could feel it in the air, thick and heavy as the August heat rolling toward Louisiana like an army.

The storm was gathering, and when it broke, it would consume them all.

August turned the Bowmont estate into a furnace. The heat was so oppressive that even the wealthy retreated into lethargy, moving slowly through their days, fanning themselves with expensive imports, while the workers labored in fields that shimmered like mirages. The cotton was ready for harvest, which meant eighteen-hour days under a sun that seemed determined to bleach the world bare.

Elijah worked until his hands split and his back screamed, until exhaustion became a kind of mercy that let him stop thinking about the impossibility of what he felt. But even exhaustion could not erase Elellanena from his mind. She was there in every moment—in the way the light fell through the trees, in the sound of wind through magnolia, in the ache in his chest that had nothing to do with labor.

Elellanena, for her part, had become someone she barely recognized. The proper governor’s wife, who had moved through life like a wound-up doll, had been replaced by a woman who lived only for stolen moments—for the brief encounters in the garden before dawn, for the seconds when she could see Elijah from a window and know he was alive, was real, was still in the world.

They could not speak anymore. Not after Cole’s interruption in the workshed. The overseer had begun watching them both with the focused attention of a hunter who had found a trail. He appeared wherever Elellanena walked, his presence a constant reminder of surveillance and threat. He assigned Elijah to the farthest fields, the hardest labor, the positions where he would be most visible and most controlled.

It was a kind of torture—to be so close and yet impossibly separate, to see each other across distances that might as well have been oceans.

Elellanena felt it like physical pain, a constant pressure in her chest that no amount of laudanum or prayer could ease.

So she did something reckless.

She began to write letters.

They started as a way to ease the pressure building inside her—thoughts and feelings she had no one else to share with. Confessions she could not speak aloud.

She wrote late at night in her private sitting room by candlelight, her hand moving across paper in loops and curves that felt like prayers or spells or the mapping of forbidden territory.

She wrote about her childhood—about the girl she had been before her father traded her future for political advantage. She wrote about her marriage, about the slow death of living without intimacy or understanding. She wrote about meeting Elijah, about the way something dormant inside her had awakened, about the terror and exhilaration of feeling alive for the first time.

She did not intend to send them at first.

But after two weeks of silence—of seeing him only from afar—of the crushing loneliness that came from touching something real and having it torn away—she could not bear it anymore.

She found a way.

There was a girl named Dinina, sixteen years old, who worked in the main house as a chambermaid.

She was small and quiet, clever in the way people had to be clever to survive—attentive without seeming to pay attention, present without being noticed, sharp enough to understand the danger of powerful people’s secrets.

Elellanena approached her one evening when the rest of the household was at dinner.

“Dinina,” she said quietly. “I need your help with something.”

The girl’s eyes went wide with fear. Requests from the powerful often meant danger—either for the one being asked, or for someone they loved.

“Yes, ma’am,” Dinina said carefully.

Elellanena handed her a folded piece of paper sealed with wax. “I need you to give this to Elijah, the man who works in the fields. Do you know who I mean?”

Dinina’s expression shifted to something close to terror. “Ma’am, I—”

“Please.” Elellanena’s voice cracked with urgency. “I know what I’m asking. I know the danger. But I have no one else. And I…” She stopped, trying to find words that conveyed urgency without saying too much. “I need him to know something. Something important.”

“Mrs. Bowmont, if they catch me—”

“They won’t.” The words came out before Elellanena could stop them, and she heard the ugliness in their truth. “You can move through spaces I can’t. They don’t watch you the way they watch me. I’m sorry. That wasn’t— I just mean you can reach him when I can’t. Please, Dinina. Please.”

Dinina looked at the letter like it was a snake—something that could strike and poison and ruin everything.

But she also saw something in Elellanena’s face that maybe reminded her that even privilege could become a kind of cage—that pain could exist behind silk.

“If I do this,” Dinina said slowly, “you got to promise me something. When this blow up—and it will, ma’am, it always do—you remember I was just following orders. That I didn’t have no choice. That I was scared and you was the governor’s wife and I couldn’t say no.”

The words hit like a cold bucket of reality.

Elellanena understood what Dinina was really saying: when this ends badly, I need you to protect me. I need you to lie for me. I need you to remember I have no power here.

“I promise,” Elellanena said. “I’ll protect you, no matter what happens.”

Dinina took the letter and tucked it into her apron, already planning how to reach Elijah without being seen, calculating risk like a general planning a campaign.

Because that was what survival looked like for people with no rights, no protection, no margin for error.

That night, during the brief window between dinner service and bed—when the house workers had a few minutes that almost resembled their own—Dinina slipped out to the quarters where the field hands slept.

She found Elijah sitting outside his cabin, too hot to sleep inside, staring at nothing with the exhausted thousand-yard gaze of someone who had spent the day being worked like machinery.

“Got something for you,” Dinina whispered, pressing the letter into his hand. “From the big house. From—”

She didn’t say Elellanena’s name. Names had power. Names could become testimony.

Elijah looked at the sealed paper in his hand like it was both treasure and trap.

“Who else know about this?”

“Just me,” Dinina said. “And I’m trying real hard to forget I know.”

“Smart girl.”

“No such thing as a smart enslaved girl,” Dinina replied with bitter wisdom beyond her years. “Just lucky ones and dead ones. Try to stay lucky.”

She disappeared back toward the main house, leaving Elijah alone with the letter and the knowledge that opening it would change everything.

He waited until everyone else was asleep. Then, by the light of a carefully shielded candle, he broke the wax seal and read Elellanena’s handwriting for the first time.

Elijah,

I do not know if this will reach you. I do not know if you will want to read it if it does, but I have to try because the silence is unbearable and I need you to know things I cannot say aloud.

I was empty before I met you. I know that sounds dramatic, but it is true. I moved through my life like a ghost, performing a role, saying lines someone else had written, existing entirely for other people’s benefit. I had forgotten what it felt like to want something, to need something, to feel anything beyond obligation and fear.

And then I saw you, and something woke up inside me that I didn’t even know had been sleeping.

I know this is impossible. I know what the world says about people like us reaching for each other. I know the danger. God, I know the danger. Every moment I think about you is a moment I risk your safety. And that knowledge is a weight I carry like stones in my pockets.

But I cannot stop. I have tried. I have prayed for discipline and wisdom and the strength to let go of this madness. But all I feel is more desperate, more hollow, more aware that if I cannot see you, cannot speak to you, cannot know that you exist and think of me sometimes—then I am back to being empty, and I cannot bear it.

You said in the workshed that some things are worth the hurt. I think about those words constantly. I think about what it means to choose pain over numbness, danger over safety, feeling over mere endurance. And I realized maybe that is what being alive actually means.

I don’t know what I am asking from you. I have no right to ask anything. You owe me nothing. I am part of the system that has stolen everything from you, and no amount of feeling can change that injustice.

But if there is any part of you that feels what I feel, that sees what I see when I look at you—if there is any possibility of something real between us, even if it can only exist in letters and shadows and stolen moments—please write back.

Please let me know I’m not alone in this madness. Please let me know I matter to you the way you matter to me.

Yours in ways I have no right to be,

Elellanena

Elijah read the letter three times, his hands shaking, his throat tight with emotions he had no safe way to show. She had put into words everything he felt but could never say, had named the impossible thing growing between them with a clarity that was both beautiful and terrifying.

Writing back was reckless.

It created evidence. It made the invisible visible. It handed enemies what they would need to destroy them both.

He should burn the letter. He should protect himself the way he had learned to protect himself since the moment he understood he was considered property.

But he didn’t burn it.

Instead, he found a stub of pencil and a scrap of paper, and in handwriting careful and cramped from years of secretly teaching himself to read and write—skills illegal for him to possess—he wrote back.

Elellanena,

You talk about being empty before you met me. I understand that more than you know.

I been hollow inside since I was eight years old and first understood my life wasn’t never going to be mine. Hollow since they sold my wife. Hollow since I held my daughter for the last time and knew I couldn’t save her. Hollow in all the ways that matter, except my body still moving, still doing what it told to do.

Then you walked into that stable and looked at me like I was a man instead of a thing. And something I thought was gone forever started breathing again.

I’m scared, Elellanena. More scared than I ever been. And I been scared plenty. Because hope is dangerous for people like me. Wanting things is dangerous. Feeling things is dangerous.

They teach us from children the only way to survive is to bury everything inside that makes us human. To become machines that work and obey and never complain. But you making me remember I got a heart. And hearts can break. And breaking going to hurt worse than anything Cole ever done to me.

I think about you all the time. In the fields when the sun so hot I can barely see straight. In the night when I can’t sleep. In the moments between moments when I let myself forget what I am and just feel what I feel.

And what I feel is something I got no words for. Something I got no right to feel. Something that might ruin us both. But yes—you matter to me. More than anything has mattered in longer than I can remember.

And if that makes me a fool, if that seals my fate, if that brings down everything—at least I got to feel it. At least I got to be alive, truly alive for a little while.

Write to me again, please. Even if it dangerous, even if it wrong, even if we both know how this probably going to end—let me be alive a little longer.

Elijah

The letters continued through August and into September. Dinina became their unlikely courier, moving between the worlds of house and field with messages hidden in her apron, her sleeves, once even in the lining of a laundry basket.

She did it partly because she had no real choice, partly because she was paid in small favors Elellanena could grant, but mostly because she understood something the powerful rarely did:

People held in bondage still had hearts. Still had lives. Still had desperate reaches for happiness in a world designed to deny them joy. Dinina had seen the way Elellanena and Elijah looked at each other in the workshed, and it reminded her of the way her own parents had looked before they were sold to different owners—before love became just another thing that could be taken.

So she carried the letters even though it terrified her, even though she knew it could get her beaten, sold, or worse.

She carried them because sometimes you had to do something dangerous just to remember you were human.

The letters grew longer, more intimate, more honest. Elellanena wrote about her childhood, about her mother who had died when she was twelve, about the suffocating expectations of southern womanhood.

Elijah wrote about his life before slavery, the fragments of memory from a childhood that seemed to belong to someone else entirely. They wrote about books Elellanena had read and how Elijah wished he could read openly. They wrote about dreams they had—futures they could never inhabit—worlds where they might simply be two people who cared for each other without law or custom or threat standing between them.

They wrote about love, though they rarely used the word. It felt too dangerous, too final, too much like a confession that could be held up in judgment.

But it was there in every line:

I see you. I know you. You matter.

And then, in late September, everything changed.

Governor Charles Bowmont found the letters.

He had not been searching for them specifically. He had been searching Elellanena’s private chambers for something else—her jewelry box key—because he needed to “borrow” a valuable necklace as a gift for a political ally’s wife.

Elellanena was out calling on neighbors, and he had taken the opportunity to enter her rooms, something he rarely did. They maintained separate lives, separate spaces—a marriage of display rather than tenderness.

But when he opened the drawer of her writing desk, he found instead a folded piece of paper.

Curious—because Elellanena was usually meticulous—he opened it and read the first letter Elijah had written back.

For a long moment, Charles Bowmont stood absolutely still, the letter in his hand, his face showing nothing. He had built his career on controlling expression, on never revealing thought or emotion until it served him.

But behind the carefully maintained mask, something cold began to unfold.

He read the letter again.

Then he systematically searched Elellanena’s desk until he found the others—eight in total—hidden in drawers and compartments: a secret correspondence that had been happening under his roof between his wife and a man the law said he owned.

He read them all.

Every word. Every confession. Every expression of feeling that should not exist, could not be tolerated—because it represented a violation so fundamental it shook the very order he had spent his life defending.

When he finished, Charles Bowmont carefully folded the letters, placed them in his coat pocket, and left his wife’s chambers.

He walked downstairs through the grand foyer with its marble floors and crystal chandelier, out onto the veranda where he could see the fields stretching into the distance.

He stood there for a long time, smoking a cigar, thinking.

Some men would have acted immediately in fury.

But Charles Bowmont was not most men.

He was a politician. A strategist. A man who understood that revenge was most effective when served with patience and precision.

He would not rush. He would not be impulsive.

He would plan.

Because this was not just about a wife’s betrayal or an enslaved man’s “presumption.”

This was about order. Power. The principle that some people owned other people. That some lives mattered and others did not. That the hierarchy must hold.

And Elellanena and Elijah had dared—through ink and longing—to suggest the hierarchy was a lie.

Not intimacy. There had been plenty of exploitation across racial lines in the South, and it was tolerated as long as it was one-directional and backed by power.

But this—this mutual recognition, this insistence on each other’s humanity—threatened the structure itself.

Charles Bowmont would destroy everything before he let that stand.

He finished his cigar, crushed it under his boot, and went inside to plan.

Elellanena knew something was wrong the moment she returned home that evening.

There was a quality to the silence that felt charged—dangerous—like the air before lightning. The servants moved through the house with unusual speed, eyes averted, faces carefully blank in the way that meant they knew something terrible but could not speak of it.

Dinina found her in the upstairs hallway, her young face tight with fear.

“Ma’am,” she whispered urgently. “The governor been in your chambers. He—”

She couldn’t finish, but she didn’t need to.

Elellanena understood immediately.

The letters.

Her blood turned to ice.

She went to her chambers first, moving fast, heart hammering. The drawer where she had hidden the letters was open—empty. The other hiding places, too. Nothing. All gone.

For a moment she could not breathe. The room tilted, reality turning into something unreal.

This was the end.

And her first thought was not for herself.

Elijah.

She had to warn him. Had to get word to him before Charles acted—because she understood her husband well enough to know where the worst consequences would fall.

White women could be explained away, cast as fragile, misguided, “unwell.”

But a Black man who had dared to write, dared to claim feeling, dared to be seen as equal—

There would be no mercy.

She found Dinina again.

“You have to warn him,” Elellanena said, gripping the girl’s thin shoulders. “You have to tell Elijah to run tonight. Now.”

Dinina’s face crumpled. “Ma’am,” she sobbed, “it too late. Cole and three other men already went to get him. The governor sent them an hour ago.”

Elellanena felt the floor drop out from under her.

No.

She ran down the stairs, through the house, out into the humid September evening, her dress tangling around her legs, her hair coming loose, propriety abandoned entirely.

She ran toward the quarters—toward the place they would take him—toward whatever nightmare was already unfolding.

She saw them before she reached the buildings: a cluster of men near the overseer’s house, torchlight cutting through darkness, shadows thrown tall and sharp against the ground.

Cole stood in the center, and next to him—hands bound, face already marked by rough handling—was Elijah.

“Stop!” Elellanena screamed, her voice raw. “Stop this now!”

The men turned, surprise and discomfort crossing their faces. A white woman running into the quarters at night, hair disordered, dress torn—an unthinkable breach of every code of southern femininity.

Cole’s expression shifted to something satisfied.

“Mrs. Bowmont,” he said. “You should return to the house. This ain’t business for a lady to witness.”

“I said stop.”

Elellanena reached the circle of men, chest heaving, eyes locked on Elijah’s.

He looked at her with an expression that broke her—sad inevitability, as if he had always known this was how it would end, and was almost relieved that the waiting was over.

“Ellanena,” he said quietly. “Go back. Don’t make this worse.”

“Worse?” She let out a sound that was half laugh, half sob. “How could this possibly be worse?”

“That’s enough.”

Charles Bowmont’s voice cut through the chaos like a blade.

He approached from the direction of the main house, walking slowly, deliberately, his face composed into cold fury.

“Eleanor. Return to the house. Immediately.”

“No.”

The word hung in the air like an explosion.

Wives did not refuse husbands in this world. Women did not defy men in public—especially not before the enslaved people who might learn that defiance was possible.

Charles moved closer, voice dropping into something low and dangerous.

“You will return to the house, or I will have you carried there. Do not test me.”

“Then have me carried,” Elellanena said, shaking, voice steady. “Because I am not leaving him.”

For a moment something flickered across Charles’s face—shock, perhaps, or the realization that his wife had become someone he did not recognize.

“Do you understand what you’ve done?” Charles asked. “Do you comprehend the scandal, the humiliation, the destruction of everything I’ve built?”

“I understand that I have come to care for a man who is more honest than you will ever be,” Elellanena said.

And once the words were out, she felt a strange lightness, as if speaking truth was its own kind of freedom.

“I understand that I spent fifteen years being your decoration, your proof of ‘civilization,’ your pretty possession. And I understand that for the first time, I have felt like a human being instead of an ornament.”

Charles’s hand moved so fast she barely saw it. The strike knocked her sideways, stars flaring behind her eyes, her mouth tasting metallic.

She heard Elijah make a sound of fury and saw him surge forward before three men seized him, holding him back with practiced brutality.

“Don’t you touch her!” Elijah shouted, fighting against their grip.

And for a moment the mask of careful submission fell away, revealing the man underneath—the one forced to hide intelligence, strength, and every human feeling the system tried to strip away.

“You see,” Charles said to the men, voice carrying a terrible satisfaction. “You see the audacity. This man thinks he has the right to defend a white woman. Thinks he has the right to feel anything but gratitude for his station. This is what happens when they are allowed to forget their place.”

“He has done nothing wrong,” Elellanena said, forcing herself upright. “We wrote letters. We spoke. We—”

She stopped, realizing any explanation would only tighten the snare.

There was no defense that could save him. No argument that could reach the fortress of wounded pride and power.

“You wrote letters,” Charles repeated, pulling folded papers from his pocket. “Yes. I read them. Every word. Letters between my wife and a man I own. Between a woman of the highest standing and a field worker who is not even permitted to be taught to read and write.”

He turned to Elijah. “Though apparently you taught yourself. Another offense. Another example of why discipline must be absolute.”

“If you harm him,” Elellanena said, voice shaking, “I will never forgive you. I will leave you. I will make sure every person of consequence from here to New Orleans knows exactly what kind of man you are.”

Charles laughed—genuinely amused.

“Leave me with what resources? What money? What protection? You are my wife, Elellanena. Legally, you are bound to me. You can threaten all you like, but you have no power here. You never did. You only had my permission to pretend.”

The truth hit like another blow.

In the eyes of law and society, she had no independent existence. She was Mrs. Charles Bowmont—an extension of her husband, a possession transferred from father to husband.

She could not own property. Could not sign contracts. Could not walk away without consequence or permission.

She had always known it, in theory.

Facing it now—seeing the trap close completely—was devastation.

“So here is what will happen,” Charles continued, voice taking on the tone of a judge. “You will be sent to your sister’s house in Charleston. Six months. We will tell people you had a nervous collapse and require rest. They will believe it because it is comfortable to believe.”

He turned to Elijah.

“And you—teaching yourself to read, corresponding with my wife, pretending you can be what you can never be—your punishment will be fitting.”

Elellanena’s stomach dropped. The way he said fitting meant something designed to break, not simply to end.

“I am selling you,” Charles said, watching Elijah’s face. “Tomorrow morning. To a cotton operation in Mississippi. You’ve heard of it.”

Even in torchlight, Elellanena saw Elijah’s face drain of color.

Everyone had heard of that place. It was a death sentence disguised as commerce—an environment designed to grind people down until there was nothing left.

“You cannot,” Elellanena whispered. “Charles, please.”

“I can. And I will.” His voice was flat. “He will be worked until he has nothing left. And you will spend the rest of your life knowing your choices led to this.”

Elellanena lunged toward Charles, but Cole seized her arms.

“You are a monster,” she said, voice shaking with fury. “He is innocent. We did nothing but write. Nothing but feel.”

“Innocence and guilt are not measured by your feelings,” Charles said coldly. “They are measured by order—by the laws of God and man that separate the master from the enslaved. That order must be restored.”

He gestured to Cole. “Take him to the holding cell. Make sure he is ready for transport at dawn.”

Then he looked at Elellanena, expression almost gentle—almost.

“Take her to her chambers. Lock the door. Post guards. She speaks to no one until her carriage leaves tomorrow.”

“I hate you,” Elellanena said. The words were quiet, absolute. “For as long as I breathe, I will hate you.”

“I can live with that,” Charles replied, “as long as you do so quietly and without further scandal.”

They dragged Elijah away, and he did not fight. Fighting would only add more punishment to a sentence already carved into stone.

As they pulled him past Elellanena, their eyes met one last time.

“I’m sorry,” she mouthed, tears pouring down her face.

He shook his head slightly—as if to say there was nothing to apologize for. As if he would do it again. As if being seen, even briefly, had been worth the price.

Then he was gone, swallowed by darkness.

Elellanena was dragged back toward the mansion, her sobs echoing through the humid night.

Locked in her chamber, guarded, she collapsed to the floor and wept until she had no tears left.

She had destroyed him. Her longing, her refusal to accept the prison of her life—she had set the trap that would crush him.

Around midnight she heard commotion outside—movement, shouting, the chaos of something happening.

She ran to the window.

Flames.

Not the main buildings, but smaller structures—storage sheds, the holding cell where Elijah had been taken. Fire climbed into the night, painting everything orange and terrible.

Elellanena pressed her hands to the glass, understanding instantly: someone had decided that escape through fire was better than slow ruin in Mississippi.

Whether it was Elijah, or others who risked everything to help him, she would never know.

But she prayed—prayed with a force that surprised her—that he had made it out, that he was running into darkness toward something better, that he would survive.

Within an hour, the fire was contained. The main house was never in danger.

But in the smoke and confusion, one truth emerged:

Elijah was gone.

The holding cell stood open, the lock broken from the outside.

No trace.

Dogs were sent out, patrols organized, rewards posted.

But rain began to fall just after midnight, washing away the trail.

Charles was furious, but an escape was a financial loss, not an unheard-of one. And he had larger concerns: protecting his political future, shaping the story, ensuring his wife’s disgrace did not stain everything he had built.

Elellanena was sent to Charleston the next day, as planned.

She went quietly, numb, feeling like all life had been drained out of her.

The letters were destroyed. The story rewritten into something easier to swallow: a wife who had suffered a breakdown, a man who had “taken advantage,” a husband who handled it discreetly.

Society accepted the explanation because it wanted to.

Because the alternative—that a white woman and a Black man had genuinely cared for each other, had dared to see each other as human—was too threatening to name.

But Elellanena knew the truth.

And in Charleston, sitting in her sister’s drawing room, surrounded by pity and condescension, she made a decision.

She would survive the exile. She would return. She would play the role expected of her.

But she would never forgive.

And she would never stop searching for signs that Elijah had survived—that he had made it north—that somewhere in this vast country he was alive and free, and remembered her.

It was a small hope.

But it was all she had.

And in the swamps and forests, moving by night, guided by the stars, drinking from streams, eating what he could find or steal, Elijah kept moving.

His body was weakened from the beating Cole had given him before the fire. His hands were raw from forcing the lock. But he was alive.

And for the first time in his life, he was moving toward something that belonged to him.

Every night before he slept in whatever hiding place he found, he thought of Elellanena—her face, her voice, her letters, the brief impossible thing they had shared.

Some loves, he thought, are worth risking everything for.

And this one—maybe—was worth living for.

So he kept moving north, carrying her memory like a light in the dark.

Six months became a year. Then two.

Elellanena returned from Charleston in the spring of 1848—thinner than when she left, quieter, her beauty dimmed by something that looked like grief but moved like rage.

She played her role with mechanical precision: the penitent wife, the recovered invalid, the woman who had learned her lesson.

Charles accepted her because separation would have been more scandal than reconciliation.

They resumed their separate lives under the same roof, barely speaking, meeting only when obligation demanded a performance of marriage.

At night, Elellanena stared at the ceiling, feeling like a ghost haunting her own life.

There was no word of Elijah. He had not been captured, which meant either he had made it north—or he had disappeared somewhere along the way, his body never found.

Elellanena chose to believe the former.

She had to.

Because the alternative would have crushed her.

The estate continued as it always had. Cotton planted and harvested. People worked, suffered, died, and were replaced. Charles’s career advanced. The world turned according to its cruel logic.

Nothing changed—except Elellanena now understood exactly how much she despised that world and everything it represented.

She began doing small things—acts of quiet defiance that could pass as ordinary.

She taught several house servants to read in secret, hiding books in her rooms, holding lessons behind locked doors. She arranged for extra food to be sent to the quarters. For medicine when illness struck. For small kindnesses that could not undo the injustice, but could ease individual suffering.

Dinina became her ally. The girl who had carried the letters grew into a woman—sharper, more cautious, but still willing to risk herself for small moments of resistance.

“You think he made it north?” Dinina asked one day in late 1849 as they sorted Elellanena’s wardrobe, pretending to organize while really stealing a moment to speak.

“I have to believe he did,” Elellanena said. “I have to believe it meant something.”

“Maybe it did,” Dinina replied quietly. “Maybe just trying was the something. Maybe feeling human for a minute was worth it, even if it ended bad.”

Elellanena studied the young woman—still trapped, still finding ways to survive with intelligence and fierce dignity.

“You’re wise beyond your years,” she said.

“Ain’t about wisdom,” Dinina answered. “It’s about what you got to tell yourself to get through the day.”

The years passed: 1850, 1851.

The country strained under the contradictions of slavery. People spoke of compromise, of stability, but tension lived in every conversation. As more people fled north, as abolitionist voices grew louder, as the economic machine built on human bondage showed cracks, Charles grew increasingly paranoid—about rebellion, about “outside influence,” about maintaining control through harsher discipline.

Cole was given freer rein.

Punishments became more severe. Fear became constant.

Elellanena watched with horror and helplessness. She had no formal power to stop it. Her small kindnesses were drops in an ocean.

The guilt ate at her, but so did the anger.

And beneath both, a question kept rising:

What would Elijah want her to do?

If he was alive, if he was free, if he thought of her at all—what would he want her legacy to be?

In the winter of 1852, Elellanena made a decision.

She began documenting everything—writing down names, stories, family ties, the injustices people suffered. She recorded Cole’s cruelty in careful detail. She noted Charles’s dealings, his corruption, the ways he maintained power through fear.

She did not know what she would do with it.

But she gathered it, organized it, hid it in places no one would think to search.

It was dangerous work. If Charles discovered it, she could be removed, silenced, declared unwell—cut off from the only ways she could help.

But she did it anyway, because it was the only resistance available to her, the only way to honor what she and Elijah had been, the only path toward making her life mean more than decorative suffering.

Mama Saraphene noticed the change. Older now, bent by decades of labor, she still saw everything.

“You walking a dangerous road, Miss Ellanena,” she said one day in the kitchen garden.

“I know.”

“You think words on paper going to change what this is?”

“I think,” Elellanena said slowly, “someone needs to bear witness. Someone needs to say this happened. These people existed. These crimes were committed. Even if nobody ever reads it—someone needs to write it down.”

Saraphene studied her for a long moment. Then she nodded once.

“My grandbaby,” she said softly, “the one they sold off last year—her name was Ruth. She was twelve. She could sing like an angel. I want you to write that down. I want somebody to remember she existed.”

“I will,” Elellanena promised. “I’ll write about Ruth. About everyone.”

It became a kind of mission.

People began coming to Elellanena with their stories—the names of children taken, spouses sold, parents lost. She wrote it all down, building a record that was both memorial and indictment.

They risked themselves by trusting her. She risked herself by listening.

But the need to be remembered—to have one’s existence acknowledged—was stronger than fear.

Then, in the spring of 1853, something arrived that changed everything.

A letter.

Not through normal channels. Not officially addressed to Elellanena. It was slipped to Dinina by a traveling peddler—a free Black man from Pennsylvania—part of a network that moved information and, sometimes, people.

Dinina brought it to Elellanena, hands shaking.

Elellanena opened it with trembling fingers.

The handwriting was different—more confident, more practiced.

But she knew immediately.

Elellanena,

I’m alive. I made it north. It took two years of hiding and running and near-death more times than I can count. But I’m in Canada now. I’m free.

I shouldn’t write to you. I know the danger. But I had to let you know I survived—that what we had wasn’t just ruined, that something good came from all that pain.

I learned to read better here. Learned to write proper. Got work as a carpenter. Got a small room that belongs to me and nobody can take it away.

I wake up every morning and remember I’m not property anymore.

And I think about you every day.

I know you probably still married. I know you probably can’t leave. I’m not asking you to. I just wanted you to know the risk we took wasn’t for nothing.

You gave me something to live for when I had forgotten how to want to live. You made me remember I was human. And now I’m free.

And being free—being whole—being able to choose my own path—that’s partly because you saw me when nobody else did.

Thank you for seeing me. For valuing me. For caring when the world said it was impossible.

Yours always,

Elijah

Elellanena read it three times, tears streaming down her face, her whole body shaking with relief and grief and something that felt like purpose crystallizing into action.

She found Dinina.

“I need you to help me do something reckless,” she said.

Dinina didn’t look shocked.

She looked like she’d been waiting.

“I’ve been wondering when you was going to decide,” Dinina said quietly. “Been watching you get thinner, sadder, meaner at the world every year. Figured eventually you’d have to choose between fading here or living somewhere else.”

“I can’t just leave,” Elellanena said, even as her mind tried to build the path.

“No,” Dinina interrupted, “but you got jewelry. Things you can sell. And you got me. And I got connections to people who help folks go north.”

Elellanena stared. “You’re part of the network.”

“Not officially,” Dinina said. “But I know people who know people. And if you serious—if you ready to give up everything you got here, even though it ain’t much—I can get you connected.”

“What about you?” Elellanena asked. “If I leave and Charles finds out you helped—he’ll destroy you.”

“Yeah,” Dinina said matter-of-fact. “Probably. But I’m tired, Miss Ellanena. Tired of being scared. Tired of watching people I love get sold or beaten or worked into the ground. Tired of surviving instead of living. So maybe this my chance too. Maybe I go north with you. Maybe we both get free.”

Hope—small, bright, terrifying—stirred in Elellanena’s chest.

They began planning in secret. It would take months: resources, routes, cover stories, contacts.

Elellanena sold jewelry piece by piece, claiming repairs. She gathered clothing suited to travel. She prepared to take her records—evidence of what she had witnessed—and she wrote back to Elijah through the same network.

Elijah, I’m coming. I don’t know when or exactly how, but I’m coming north. I refuse to spend the rest of my life as a ghost in this house, married to a man I despise, trapped inside a system that destroys everything human.

You gave me courage. Wait for me. However long it takes—wait for me.

I love you. I have always loved you, and I’m done pretending I don’t.

Elellanena

The letter was sent in August 1853.

Elellanena began finalizing everything.

But in September, disaster struck.

Charles discovered her documentation.

Not by chance. He had been watching her, suspicious of her meetings with Dinina, her questions about travel and routes north. He found the pages—names, dates, testimony, careful notes about cruelty and corruption.

Evidence that could ruin him.

His rage was cold, methodical.

He did not confront her immediately.

He planned—just as he had planned years earlier.

But this time he would not settle for exile or silence.

This time he would ensure she could never threaten him again.

On the night of October 15th, 1853, Charles Bowmont set his plan in motion.

Fire.

It began after midnight in the east wing—dry furniture, draperies, the kindling of wealth.

By the time the house workers realized what was happening, flames had climbed the walls and raced through corridors like something hungry.

Elellanena woke to smoke and shouting. Disoriented, she reached for the door—and found it locked from the outside.

Terror poured through her.

She pounded, screamed, but the roar swallowed her voice.

Smoke seeped under the door—thin gray promises of suffocation.

Charles had locked her in.

It wasn’t accident.

It was murder arranged to look like tragedy.

She forced herself to think.

A window.

She ran to it—found it fastened shut.

He had sealed everything, likely earlier that day.

But Elellanena Bowmont had not survived the last years by surrendering.

She grabbed a heavy candlestick and smashed the glass.

It shattered, raining down in glittering shards to the ground below.

Not a survivable jump.

But better than waiting.

She was clearing the frame when the door crashed open.

She spun—expecting Charles.

Instead: Dinina, face streaked with soot, eyes wild with determination. Behind her, Mama Saraphene and two other women.

“Come on!” Dinina shouted. “No time!”

They ran through corridors filling with smoke. Flames consumed the east wing, advancing fast. The heat was overwhelming, turning breath into pain. Above them, timbers groaned.

They reached the main staircase just as the chandelier fell—crystal exploding across marble like a deadly hail.

Out the front door onto the lawn—into chaos: servants and enslaved people forming water lines, dragging belongings, shouting, coughing, trying to make sense of disaster.

But Elellanena did not see Charles.

“Where’s the governor?” she asked, voice loud over the roar.

Dinina shook her head. “Ain’t seen him since it started.”

Elellanena scanned the crowd again.

No Charles. No Cole either.

“He’s inside,” Elellanena said suddenly, certain. “He started this, but something went wrong. He got trapped.”

“Good,” Dinina said flatly. “Let him go.”

Elellanena looked at her and understood that Dinina had earned the right to that coldness. They all had.

But Elellanena found she could not stand there and do nothing. Fifteen years beside a monster did not create love, but it created history—the tangled, bitter familiarity of a shared life.

She wanted justice. She wanted him held accountable.

But she could not watch him die like this.

“I have to try,” she said.

Dinina grabbed her arm. “Ma’am, you can’t—”

But Elellanena was already running back toward the mansion, robe over her mouth, plunging into smoke and heat.

Inside was a nightmare. Flames climbed walls. Visibility collapsed. Heat pressed in like a weight.

“Charles!” she screamed. “Charles, where are you?”

She found him in his study—pinned under a fallen beam, face ashen with pain.

When he saw her, surprise crossed his expression.

“You,” he rasped. “You came back.”

“I’m foolish,” Elellanena replied, assessing the beam. Solid oak. Immovable. “Why did you do this? Why try to kill me? I was going to leave anyway.”

“Evidence,” he gasped. “Your records. If you took them north, everything I built would be destroyed.”

“So you decided to destroy me instead.”

“You forced my hand,” he coughed. “You been forcing my hand since the day you looked at that man like he was human.”

“This is your fault,” he said weakly. “All of it.”

“I would rather have been alive in my soul than preserved in your prison,” Elellanena shot back, gripping the beam, straining uselessly. “At least I got to feel real things.”

She heard the house groaning. The floor tilted.

Time was running out.

“Go,” Charles said, voice urgent now. “You can’t save me.”

“I know,” she said, still trying. “But I have to try. Not for you. For me. So I don’t become like you.”

He let out something like a bitter laugh. “Idealistic. That was always your problem.”

“No,” she said. “My problem was marrying you at seventeen.”

The house gave another warning groan.

“Ellanena,” Charles said, frightened. “Go. Please.”

Then, as if deciding something, his voice softened.

“I don’t want you to die. Not truly. I was angry. I’m sorry—for what I did to you. For what I did to him. For all of it. Live.”

It was the first apology in fifteen years.

Too small. Too late.

But Elellanena still found herself saying, “I know.”

Then Dinina and Saraphene were there—appearing through smoke like ghosts, grabbing Elellanena’s arms.

“No!” Elellanena fought them. “We have to—”

“He done,” Saraphene said bluntly. “Even if we could move that beam, he not walking out. But you will.”

They dragged her through fire and smoke, and finally threw her out onto the lawn.

She hit the ground hard, wind knocked from her lungs.

Behind her, the center of the house collapsed with a sound like the world breaking.

Charles Bowmont died in the ruins of the mansion he had built on stolen lives.

Elellanena watched it burn through the night, sitting on the grass with Dinina beside her, neither speaking.

At dawn, gray light fell over ash and broken stone.

Elellanena realized the record she had built—the names, the testimony—was gone.

But the people were still here.

Alive.

Able to tell their stories—if anyone would listen.

“What happens now?” Dinina asked quietly.

“I don’t know,” Elellanena admitted. “Legally, the estate will pass to his brother. The plantation will continue. You’ll still be—”

“Owned,” Dinina finished. “Yeah. Nothing changed.”

Elellanena was silent for a long moment.

Then she said, “I’m still going north as soon as I can. And I’m taking anyone who wants to come.”

Dinina turned. “You serious?”

“Completely. His brother will take weeks to arrive. That’s our window.”

“They’ll chase us.”

“Probably. But some might make it. Better than nobody trying.”

Elellanena met Dinina’s eyes.

“I can’t undo what I was born into. But I can refuse to participate anymore. I can use what I have—money, connections, the fact that I’m white and can move in ways you can’t—to help people get out. It won’t be enough. But it will be something.”

Dinina studied her face.

Then she said, “Miss Elellanena, you finally growing a backbone. Took you long enough.”

Elellanena laughed—half sob, half real.

“Better late than never.”

Over the next three weeks, Elellanena orchestrated the largest escape the parish had ever seen. Using what jewelry remained and the chaos of transition, she arranged transportation for seventeen people along routes north. Some would reach Canada. Others would find safety in northern states. Some would be caught and punished harshly.

But all of them would have tried.

All of them would have chosen risk over certainty, hope over despair.

Elellanena and Dinina left together on a cold November morning, just as Charles’s brother arrived to claim what remained of the Bowmont fortune.

They moved through safe houses and sympathetic conductors, sometimes hidden under false wagon floors, sometimes walking forests at night—always north.

It took four months.

Elellanena found Elijah in a small town outside Toronto—working as a carpenter, living in a modest room that was his own, his eyes carrying less grief and more something like steady peace.

When she appeared at his door in March 1854—six and a half years after he escaped—he stared at her like she was impossible.

“Ellanena,” he whispered.

“I told you I was coming,” she said.

And then she was in his arms, both of them crying, holding each other with the desperate intensity of people who had crossed ruin to reach this moment.

They married three weeks later, startling even the free community that had sheltered him, building a home that defied the world they had fled.

Dinina found work as a seamstress. She later married a man who had also escaped bondage and spent the rest of her life helping new arrivals build steady lives in freedom.

Elellanena never returned south. She lived in Canada with Elijah for thirty-four years, raised three children who grew up free and educated, never knowing chains. She wrote accounts under a pseudonym—testimony from someone who had once benefited from the system and then chose to abandon it.

She died in 1888 at age seventy-three in a house she and Elijah built together, surrounded by children and grandchildren who carried the legacy of two people who refused the world’s definitions.

Elijah outlived her by four years.

In those years, he finished a project they had started: a memorial garden where they planted a magnolia tree for every person they had known who had died enslaved—every name Elellanena had written and lost, every life that mattered even when the world said it didn’t.

The memorial still stands today, maintained by their descendants—a place of remembrance for those who resisted, who ran, who dared to be free, who dared to care across boundaries designed to keep them apart.

Back in Louisiana, the ruins of the Bowmont mansion became a legend—a cautionary tale about pride and “transgression,” about what happens when people forget their place.

But for those who knew the real story, the ruins meant something else.

They were not a warning.

They were proof that humanity is deeper than hierarchy, that dignity outlasts the laws that deny it, and that some truths are worth risking everything to protect.

The Bowmont dynasty ended in fire and scandal as Charles had always feared.

But Elellanena and Elijah’s story—defiant, impossible, enduring—survived.

And in a world designed to crush them, that survival was victory enough.