Willowre Plantation had perfected the art of looking harmless.

By day, it was a picture designed to calm the nervous and impress the curious: white columns rinsed bright by sun and rain, magnolias hanging heavy with perfume, cotton fields rolling outward in neat, obedient lines. Travelers along the Burke County road would have seen prosperity, order, “civilization.” What they would not see—what no one ever understood until it was far too late—were the silences that lived between the trees, and the careful way fear could be trained to hide behind beauty.

On the evening of October 22, 1857, the plantation dressed itself for celebration. Lamps warmed the great hall. Polished floors caught the light like water. Crystal glasses clicked in tidy rhythms. Cigars burned slow and sweet. Six white men laughed loudly enough to smother memory, congratulating one another on another profitable season, another successful purchase, another reminder that the world still bent in their favor.

No one noticed the woman leaving the quarters just before dusk.

Manurva Hall moved without urgency, because urgency drew eyes. She walked the way a person walks when the world has decided they do not count. Shoulders slightly rounded. Head lowered. The posture of a woman who had learned the math of survival: when to disappear, when to be small, when to look exactly like what grief was “supposed” to produce—quiet, obedient, finished.

But grief had not finished Manurva.

It had sharpened her.

Eight months earlier, something inside her had split open—not as a dramatic collapse, not as a single moment of breaking, but like stone giving way to a river that had been pressing against it for years. When her daughter Patience was taken, when the wagon wheels turned and did not return, Manurva did not scream herself into ruin the way some people expected. She did not plead loudly to a God she had already lost somewhere between Calabar and Charleston, somewhere on a coastline that no longer felt like memory but like a wound that never healed.

Instead, she remembered.

She remembered the forests of her childhood. She remembered her mother’s voice, low and steady, teaching her how to stand so that the wild things would not mistake trembling for invitation. She remembered the lesson repeated more than any prayer: nothing alive rules alone. The strong depend on something. Even the strongest need a world that agrees to hold them up.

The woods beyond Willowre still remembered that truth.

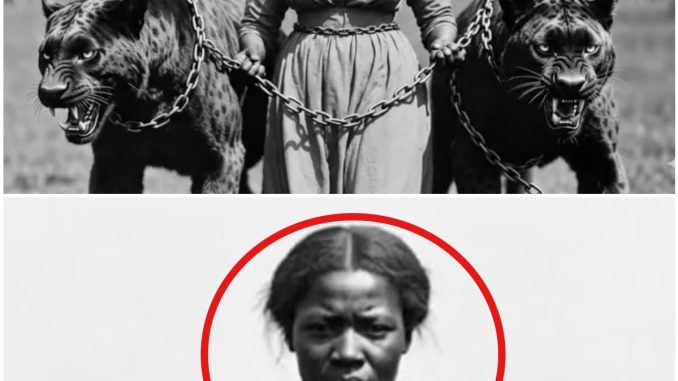

Manurva reached the ravine as the sky drained from blue into black. The cages waited where she had left them, half-hidden beneath vines and shadow. Six of them, reinforced with wood and iron gathered slowly, patiently, over months of labor no one ever bothered to notice. She built them with hands scarred by years in the fields—hands the world believed capable only of breaking, never building.

Inside the darkness, something shifted.

Low breathing. The soft scrape of claws against earth. The sound of muscle tightening, not in chaos, but in readiness.

Manurva stopped at the edge of the clearing and closed her eyes.

This was the first test.

Her mother had taught her that animals sensed intention before sound. If her mind shook now, if doubt crept in, the forest would turn its face away. She breathed in damp pine and soil, let it settle into her bones, and thought of Patience—not as she was taken, but as she once laughed, barefoot in dirt, humming songs that carried pieces of a language older than chains.

The sound that left Manurva’s throat was not a word.

It was a signal.

One by one, the cages answered.

But not the way she expected.

The first big cat—the young male who had once left a mark on her shoulder—paced the length of his enclosure, restless as if the night itself had changed. The lynx did not move at all, staring at her with unsettling clarity. And somewhere to her left, one of the cougars released a sound that was not hunger and not obedience.

It was warning.

Manurva felt it immediately.

Something was wrong.

Her training had been careful. Painfully careful. Night after night, she had tested the tones and timing, making sure the animals recognized her presence, her rhythm, her calm. These creatures knew her. They had tolerated her. Some part of her had believed that was the same as choosing her.

But standing in that clearing, she felt resistance—not defiance, but hesitation, as if the forest itself was asking a question she had not prepared to answer.

She stepped closer, lowering her voice into the cadence her mother reserved for danger.

That was when she smelled it.

Human.

Not the stale, familiar scent of the plantation that clung to everything within reach, but fresh and recent, sharp in a way that did not belong here.

Her pulse slowed instead of racing. Panic would have been a mistake. Panic was for people who believed they had many paths to choose from. Manurva had lived long enough to understand that sometimes there is only one path, and the only choice is whether you walk it steady or shaking.

She moved silently, circling the clearing, listening.

A branch snapped.

Just once.

Her hand tightened around the small knife at her waist—more habit than hope. Steel would not solve what was coming. If someone had followed her—if Silas Crowe, or one of the drivers, or one of the men in the great hall had grown curious—then everything she had built for eight months balanced on the thinnest edge.

“Come out,” she said softly, in English.

Silence.

Then, from behind a stand of young pines, a voice she did not expect spoke her name.

“Manurva.”

Marcus.

The younger driver stepped into view with his hands raised. In the dim light, his face looked pale, almost boyish. He did not look like the man who had once swung a stick to secure his small share of favor. Here, without the plantation’s performance around him, he looked like what he was.

Another trapped thing.

“I didn’t mean to follow,” he said quickly. “I swear. I just… I saw you coming here. Night after night. I knew you weren’t hunting.”

Manurva said nothing. She watched him the way predators watch prey that might still be useful.

Marcus swallowed hard. “They’re talking in the quarters,” he said. “That something’s coming. The dogs won’t settle. The birds go quiet when you pass. People notice.”

That was the first twist of the blade.

She had been careful. Careful enough that even Silas had grown bored of watching her. But fear traveled faster than proof, and enslaved people survived by reading storms before thunder showed itself.

Marcus took a step closer—and froze.

The cougar growled again, low and unmistakable, vibrating through the clearing like a warning bell.

Marcus’s eyes widened. “You brought them,” he whispered, finally understanding. “You brought… trouble.”

Manurva tilted her head slightly. “You helped take my daughter,” she said, her voice calm enough to be frightening. “Why should you walk away from this night?”

Marcus’s mouth opened, then closed. His eyes flicked toward the trees, calculating distance, speed, hope. He would not make it far.

“I didn’t know,” he said. “I swear I didn’t know what they were going to do. They never tell us everything.”

Manurva’s stare didn’t soften. “That’s what you tell yourself,” she replied. “So you can keep breathing.”

She raised her hand, preparing the command she had practiced a hundred times.

And then the lynx did something unexpected.

It turned its head—not toward Marcus, but toward the direction of the plantation.

Its ears flattened.

Another scent had reached the clearing, carried by wind.

Not just humans. Not just the plantation’s ordinary noise.

Something sharper. Torches. Metal. The faint bite of smoke in the air.

And then, distant but clear enough, voices.

A group moving together.

A searching party.

Manurva’s chest tightened for the first time that night.

Someone else knew.

She did not have time to wonder how.

Lights flared through the trees in the distance—torches, more than one, bobbing and spreading like a net being thrown.

Silas Crowe’s suspicion had returned, and suspicion on a plantation was a weapon all its own.

The forest, which had been her ally, now became a maze of consequences. If she released the animals too soon, they might scatter and expose everything. If she held them, she risked being trapped with the cages and the proof. If she turned on Marcus, she lost precious seconds. If she trusted him, she risked something worse than being caught.

She made a decision that would follow her like a shadow.

“Run,” she told him.

Marcus stared at her as if he hadn’t heard correctly. “What?”

“Run,” she repeated, her voice flat. “And if you speak about what you saw here, I promise you won’t have time to wish you hadn’t.”

He didn’t ask why she spared him. People rarely question mercy when it arrives like lightning. He turned and disappeared into the trees, footsteps swallowed by the growing noise.

Manurva moved fast.

She opened three cages—no more.

The panther pair slid out like midnight poured onto earth, vanishing toward the plantation’s edge. The lynx followed, silent as breath. She forced herself to leave the others locked, trusting that even half a plan could still cut deep.

Torches broke through the tree line moments later.

Silas Crowe’s voice rang out, loud with authority and adrenaline. “There! I knew it. I told you something was wrong with that woman.”

Manurva did not wait to be seen.

She slipped into the forest, circling wide, mind working like a blade. The night had changed. The plan was broken. Which meant she had to become something else entirely—no longer a woman with a single path, but a shadow that could turn any path into a weapon.

By the time Silas reached the clearing, the cages were empty—or worse, partially empty, their doors hanging open like questions no one wanted to answer.

“What in God’s name…” he muttered.

A scream cut him off.

Not close.

Inside the plantation.

Raw, panicked, the kind of sound that comes when people realize the world they built is not listening to them anymore.

Silas spun toward the glow of the big house as another shout rose, then another, confusion stacking into fear. Men hesitated. Dogs barked, then changed their tone, then went silent in a way that chilled the bones.

Silas ran.

He would never understand that he had been offered a kind of mercy too—just not the kind that left him comfortable.

Manurva reached the edge of the property as chaos bloomed behind her. She did not look back. She didn’t need to. The forest carried the sounds to her: boots on boards, voices breaking, a gunshot fired into darkness, the crash of something heavy overturned.

But something else carried through the night as well.

A name.

Her name.

Shouted in terror.

Shouted in disbelief.

Shouted as if saying it might restore order, might explain what could not be explained.

Manurva kept moving.

Because vengeance, she was learning, was never clean. It never stayed inside the shape you drew for it. It grew a will of its own. It demanded sacrifices you didn’t plan for. It left witnesses who would tell the story in ways you could not control.

And somewhere, far from Willowre, in Savannah, a fourteen-year-old girl still breathed.

That knowledge cut deeper than anything the plantation had ever done, because it reminded Manurva of what was still unfinished. Of what she was still chasing. Of how a mother’s love could survive even when everything else was designed to crush it.

The forest closed behind Manurva Hall, swallowing her path, her scent, her future. Willowre Plantation burned bright with torchlight and panic, but the night was far from finished.

It had only just begun.