The box was heavier than it looked.

Dr. James Mitchell noticed that first—not with his hands, but with his instinct. Years in archives had given him a strange kind of intuition: the weight of paper often hinted at the weight of what it carried. Some boxes held invoices and church newsletters. Others held echoes.

This one was labeled in fading ink: Atlantic Collections, 1890–1900.

Outside the window of Emory University’s archives, Atlanta simmered in late-summer humidity. Inside, the air was cold, precise, controlled. History preferred it that way—kept stable, unemotional, preserved. James slipped on cotton gloves and lifted the lid.

Photographs. Dozens of them. Cabinet cards, cartes de visite, studio portraits—Black families dressed in their best, staring back across more than a century. He had devoted twelve years to these images. He knew how much resolve it took, in the post-Reconstruction South, for a Black family to commission a photograph at all. Photography cost money. It required planning. It was a statement made without speaking: We are here. We exist.

He moved methodically. Image after image. Weddings. Church groups. Graduation portraits. Then—halfway down the box—his fingers paused.

Something about the tissue paper felt… intentional.

He peeled it back slowly.

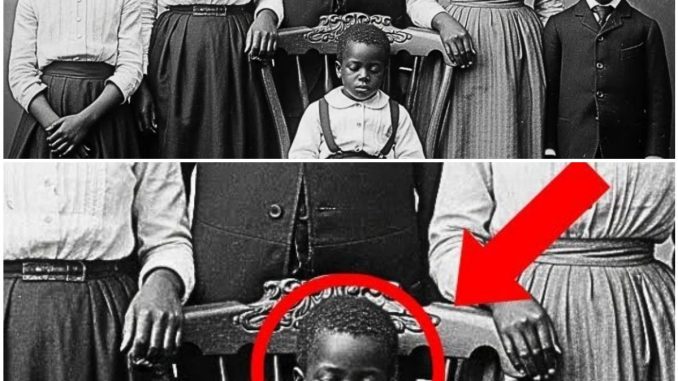

The photograph beneath showed a family of six.

A father and mother stood behind four children arranged by height. Formal clothing. Clean lines. The kind of dignity Black families insisted on even when the world refused to grant it. The father’s hand rested on the mother’s shoulder. Protective. Anchoring. Her expression was composed—but strained, as if she were holding something behind her eyes.

James leaned closer.

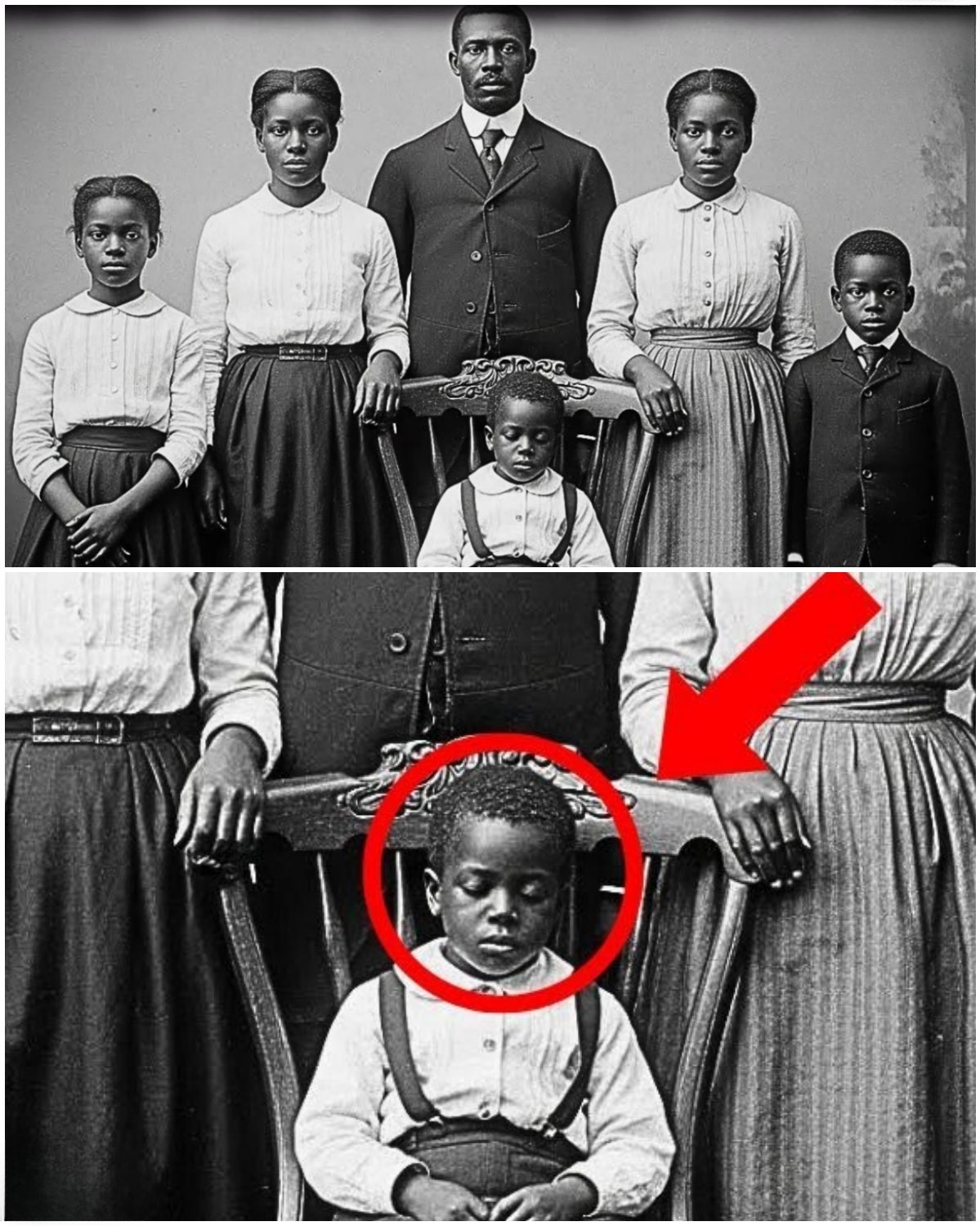

Three of the children stared straight ahead, faces solemn in the way Victorian photography demanded. But the youngest boy, seated in front, was different.

His eyes were closed.

Not squinting. Not mid-blink.

Closed.

James felt the familiar tightening in his chest—the sensation he had learned not to dismiss.

“Don’t jump,” he whispered to himself. “Observe.”

He scanned the photograph at high resolution. Pixel by pixel, the image revealed small betrayals. The boy’s hands were folded too perfectly. His posture looked unnaturally rigid. There was a faint shadow beneath the eyes that didn’t match the lighting.

James exhaled slowly.

This wasn’t a living child simply holding still.

This was a child who was no longer alive.

Memorial photography existed in the 19th century, especially for children. Illness moved quickly back then. Families recorded farewells as a final act of love. But those images were usually clear about what they were—flowers, symbolic arrangements, the quiet honesty of closed eyelids.

This photograph was different.

It was disguising the truth.

Someone had staged a final image and dared the future to notice.

James leaned back, heart thudding. Why hide a memorial inside what looked like an ordinary family portrait? Why blur the boundary between the living and the lost?

He turned the photograph over.

In faded pencil: Family, 1897.

No names. No studio stamp. No location.

That absence was its own kind of alarm.

Estate records led him to a quiet West End neighborhood. A house that had stayed in the same family’s hands for generations. The last resident, Dorothy Freeman, had died at ninety-six. No children. No public attention. But in her will, she made one request:

Donate the papers. All of them.

James requested the rest of the materials from her estate. Boxes of letters. Church programs. Receipts. The rhythm of a life preserved in fragments.

On the second day, he found the letter.

September 1897.

Dear Sister Eliza,

We received word of your terrible loss. We understand why you cannot speak of it openly. The photograph you described—showing him with the family as if he still lived—is both heartbreaking and wise. They cannot erase him if his image remains.

James read it again. And again.

“They.”

Erase.

This wasn’t only grief. This was fear.

He dug deeper.

Another letter mentioned Robert’s strength. The girls growing taller. A boy’s name appeared once, then vanished from later correspondence.

Samuel.

Church records confirmed it.

Samuel Freeman. Age eight. Died September 12, 1897.

Cause of death: not listed.

And then, in different ink, a line added later:

The Lord knows.

James felt his stomach tighten.

He knew Atlanta’s history. He knew how newspapers used coded phrases. He knew how easily a life could be reduced to a sentence and then buried beneath advertisements and weather reports.

He found a small article on microfilm. Short. Cold. Anonymous.

A young negro dealt with appropriately in West End.

No name. No age.

But the date matched.

James didn’t sleep that night.

Friendship Baptist Church stood like it always had—brick, stubborn, alive. Inside, the air smelled of old wood and memory. Mrs. Claudia Washington greeted him at the door with a look that suggested she already knew why he had come.

“You’re here about the photograph,” she said. Not a question.

Deacon Marcus Howard joined them. Silver-haired. Calm in a way that came from carrying too many stories too long.

When James showed them the image, the deacon closed his eyes.

“I wondered when someone outside the family would finally see it,” he said quietly.

The truth surfaced slowly.

Samuel Freeman had been walking home from school. A small moment. A greeting. A misunderstanding—or a lie—told by someone who wanted protection and knew exactly where to aim it.

By nightfall, men came to the Freeman house.

They took the boy.

They made the parents witness what no parent should ever be forced to witness.

The child did not pass quickly.

James’s fists tightened until his nails bit his palms. He had studied racial terror in documents. He had read testimony and reports. But hearing it spoken aloud, hearing it named as a family’s memory, carried a different weight.

“They left him as a warning,” Mrs. Washington said, voice low. “And the family understood the message.”

Report it, and you won’t be safe either.

So Robert and Eliza buried their son quietly. And then they did something brave.

They documented him.

Dr. Nicole Freeman—Dorothy’s grand-niece—held the photograph later with trembling hands.

“There he is,” she whispered. “They told me about him. But they never showed me this.”

Dorothy had been the keeper. The last guardian before the archive. Inside a wooden box passed down through the women of the family were relics: a child’s shoe. A pressed flower. Letters folded and refolded until the creases became permanent.

And then—another turn.

A list.

Forty-three names.

Eliza Freeman’s handwriting.

Dates. Ages. Causes written in restrained language, as if she was determined to be exact even while her heart was breaking.

Samuel Freeman, age 8 — killed after speaking to a white child.

James sat very still as he read it.

Because the photograph wasn’t an isolated act.

It was part of a system.

Eliza had been building an archive of the lost—an underground record of deaths the city refused to acknowledge, a ledger of pain written carefully so no one could pretend it never happened.

Then came another discovery.

Tucked among the letters was a note James hadn’t noticed at first—addressed not to family, but to someone else.

Mr. Davis,

If you believe as we do that memory is resistance, then you will understand why this matters.

William Davis. Black photographer. Auburn Avenue.

His ledger confirmed it.

September 15, 1897. Freeman family memorial portrait. No charge.

Underlined twice.

James felt something shift in his chest.

This wasn’t just a photograph.

It was a deliberate act of refusal.

A collaboration.

A quiet agreement between a grieving mother and a photographer who understood that images could outlive threats, that paper could be safer than speech, that history could be stored where power might not think to look.

As James began preparing his findings for publication, the pressure arrived quietly at first.

An email questioning his “interpretation.”

A phone call suggesting “restraint.”

A donor expressing discomfort.

Then a file went missing.

Then another.

Someone, even now, seemed unsettled by what Eliza Freeman had recorded.

Nicole noticed it too.

“They erased her once,” she said. “They won’t do it again.”

The exhibition opened on September 12, 2019.

One hundred and twenty-two years to the day.

People stood in silence in front of Samuel’s face. Some cried without sound. Some turned away too quickly, as if looking too long might make them responsible for remembering. Others stayed, reading every label, tracing the handwriting on the list like it was a map.

One visitor lingered.

A man who didn’t sign the guestbook.

A man who asked about Eliza’s list.

And when James returned to the archives the next morning, he found something new inside the Freeman box.

A letter he was certain had not been there before.

Undated. Unsigned.

Written in Eliza’s hand.

If you are reading this, it means they failed.

James stared at the page, pulse rising.

Because tucked inside the fold was a second list.

Shorter.

Names that did not appear in any church ledger. Names not printed in any newspaper. Names that had never been documented anywhere else.

And at the bottom—unfinished.

As if Eliza had been interrupted.

As if the record was still incomplete.

James sat back, the cold archive air suddenly feeling too thin.

Because he understood then: the photograph hadn’t finished speaking.

And neither had the past.

Some stories wait to be uncovered.

Others wait to be continued.