On a winter morning in Alaska nearly a century ago, the world felt very far away from the small town of Nome. Snow stretched endlessly across the frozen landscape, and the silence of the Arctic seemed unbreakable. Yet beneath that stillness, a quiet race against time was unfolding. It would involve ordinary people, determined sled dogs, and a husky named Balto whose story would later grow into legend.

Today, Balto is remembered not just as a dog, but as a symbol of perseverance, teamwork, and trust between humans and animals. His journey has been retold in books, classrooms, statues, and films. But where does history end and mythology begin? And what can science and historical records tell us about what truly happened during the famous Nome Serum Run of 1925?

The Remote World of Nome, Alaska

In the early 20th century, Nome was one of the most isolated communities in the United States. Located on the southern coast of Alaska’s Seward Peninsula, it was cut off from the rest of the country for much of the year. During winter, sea routes froze solid and roads were nonexistent. Travel depended almost entirely on dog sled teams following established trails across snow and ice.

At the same time, medical resources in remote regions were extremely limited. Treatments that were common in larger cities could take weeks or months to arrive, if they arrived at all. This reality set the stage for one of the most remarkable cooperative efforts in American history.

A Public Health Emergency in the Arctic

In January 1925, Nome faced a serious public health crisis caused by diphtheria, a bacterial illness that was widespread in the early 1900s. Before modern vaccination programs, diphtheria posed a significant risk, particularly to children. Although an antitoxin existed, Nome’s supply had expired, and the nearest fresh doses were hundreds of miles away.

The closest rail connection was in Nenana, nearly 700 miles from Nome. Under normal conditions, a dog sled journey of that distance could take close to a month. Given the urgency of the situation and the extreme winter weather, waiting was not an option.

Local officials, doctors, and experienced mushers agreed on a bold plan. Instead of one team making the entire journey, multiple teams would relay the medicine across Alaska in carefully planned stages. This strategy would dramatically reduce travel time and improve the chances of success.

The Great Serum Run of 1925

The plan that emerged became known as the Great Serum Run, sometimes called the Great Race of Mercy. It involved more than 20 mushers and approximately 150 sled dogs, each responsible for a specific section of the trail. These routes followed parts of what is now known as the Iditarod Trail, historically used for mail delivery and trade.

On January 27, 1925, the first musher departed from Nenana with a carefully protected container holding the antitoxin. Wrapped in insulating materials and sealed in a metal cylinder, the medicine was passed from team to team under challenging weather conditions that included strong winds, heavy snowfall, and extremely low temperatures.

Each musher relied entirely on their dogs, not only for strength and endurance, but also for navigation. In whiteout conditions, experienced lead dogs were often the only guides capable of sensing the trail beneath the snow.

Balto’s Early Life and Role

Balto was a Siberian Husky born around 1919 in Nome. He was bred by Leonhard Seppala, a highly respected musher whose dogs were known for speed and resilience. Early accounts suggest that Balto was not initially viewed as a standout leader. He was sometimes described as an average working dog, reliable but unremarkable.

However, sled dog teams depend on more than reputation. Endurance, calm behavior, and responsiveness under pressure are essential traits, especially in unfamiliar or difficult conditions. As the serum relay progressed, these qualities would become increasingly important.

Seppala himself handled one of the longest and most demanding sections of the run, guided by his experienced lead dog Togo. After completing his leg, the antitoxin was transferred to other mushers, eventually reaching Gunnar Kaasen for the final stretch toward Nome.

The Final Stretch to Nome

The last leg of the relay covered roughly 50 miles. By this point, conditions had worsened, with strong winds and near-zero visibility reported in historical records. Kaasen selected Balto as the lead dog for this portion of the journey.

According to later accounts, Balto maintained direction even when landmarks were obscured by snow. While it is difficult to verify every detail, historians generally agree that the team successfully navigated the final stretch without major setbacks.

On February 2, 1925, the sled team arrived in Nome with the antitoxin intact. The medicine was immediately distributed under medical supervision, marking the successful conclusion of the relay.

How Media Turned Balto Into a Legend

News of the serum run spread quickly beyond Alaska. Newspapers across the United States reported on the effort, often focusing on the dramatic elements of the story. Balto, as the lead dog of the final team to arrive, became the most visible symbol of the mission.

This media attention helped shape public perception. Balto was celebrated as a hero, while the broader effort involving many mushers and dogs received less recognition. This imbalance later sparked debate among historians and participants.

Leonhard Seppala, in particular, emphasized that Togo and other dogs had covered far greater distances and faced equally demanding conditions. His perspective highlights an important distinction between symbolic recognition and logistical contribution.

Science, Teamwork, and Canine Ability

From a scientific standpoint, the success of the serum run can be attributed to careful planning, biological adaptation, and teamwork. Sled dogs like Siberian Huskies are uniquely suited to cold environments due to their thick fur, efficient metabolism, and strong cardiovascular systems.

Lead dogs play a critical cognitive role. Studies on canine behavior suggest that experienced lead dogs are capable of independent decision-making, including route selection and hazard avoidance. These abilities are especially valuable in low-visibility conditions.

The relay system itself reflects principles still used in modern logistics. Breaking long routes into shorter segments reduces fatigue, allows for redundancy, and improves overall reliability. In this sense, the serum run was not just an act of bravery, but an early example of efficient emergency response planning.

Balto’s Legacy in Culture and Memory

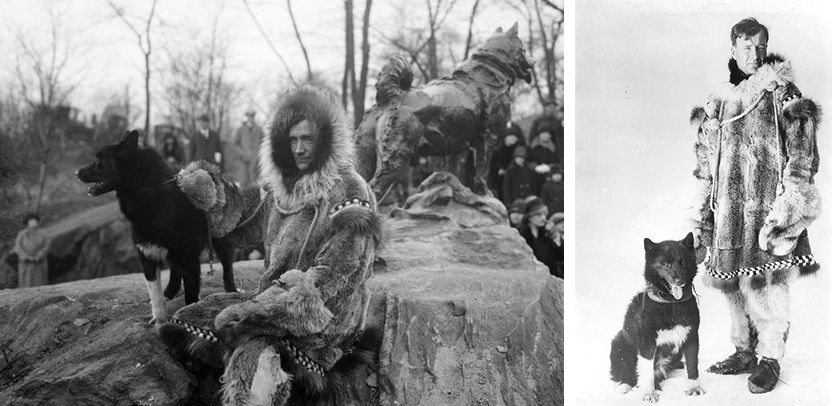

Later in 1925, Balto was honored with a statue in New York City’s Central Park. The monument remains today, bearing an inscription dedicated to the spirit of sled dogs who carried medicine across Alaska.

Balto’s fame continued to grow throughout the 20th century. His story inspired books, educational materials, and animated films that introduced new generations to the idea of animal heroism. These portrayals often simplified the narrative, focusing on Balto as a lone hero rather than part of a coordinated effort.

Balto lived out his later years away from the spotlight. After changing hands several times, he eventually found a permanent home at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where his preserved body remains on display as an artifact of American history.

History, Myth, and Why the Story Endures

The story of Balto endures because it operates on multiple levels. Historically, it represents a successful public health response under extreme conditions. Culturally, it reflects humanity’s long-standing admiration for loyalty and cooperation between species.

At the same time, the story invites reflection. Legends often emerge not because they are perfectly accurate, but because they capture shared values. Balto’s rise to fame illustrates how societies simplify complex events into memorable symbols.

Recognizing this does not diminish the achievement. Instead, it allows a fuller appreciation of everyone involved, from the doctors and planners to the mushers and dozens of sled dogs who worked together toward a common goal.

A Reflection on Human Curiosity and Storytelling

Stories like Balto’s continue to fascinate because they sit at the intersection of fact and imagination. Humans are naturally drawn to narratives that highlight resilience, cooperation, and hope in difficult circumstances.

As historical research deepens and scientific understanding grows, these stories evolve. They become less about singular heroes and more about collective effort. In that evolution, curiosity plays a central role, encouraging us to revisit the past with greater nuance and respect.

Balto’s journey, whether viewed through history, science, or cultural memory, reminds us that meaningful achievements are rarely the work of one individual alone. They are the result of many small actions, aligned by purpose, and remembered through the stories we choose to tell.

Sources

All That’s Interesting. “The True Story of Balto, the Husky That Helped Save an Entire Alaskan Town.”

National Park Service. “The Serum Run of 1925.”

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Diphtheria History and Overview.”

Cleveland Museum of Natural History. “Balto Collection.”

Smithsonian Magazine. “The Real Story of the 1925 Serum Run to Nome.”