On the night of October 23, 1856, in Halifax County, Virginia, something that felt impossible to the people who witnessed it began to unfold.

For fifteen years, a man had been treated like a spectacle—paraded for profit, measured for “research,” and worked until his body became a machine. His life was managed with iron, routines, and rules designed to make him forget he was human.

That night, the routine broke.

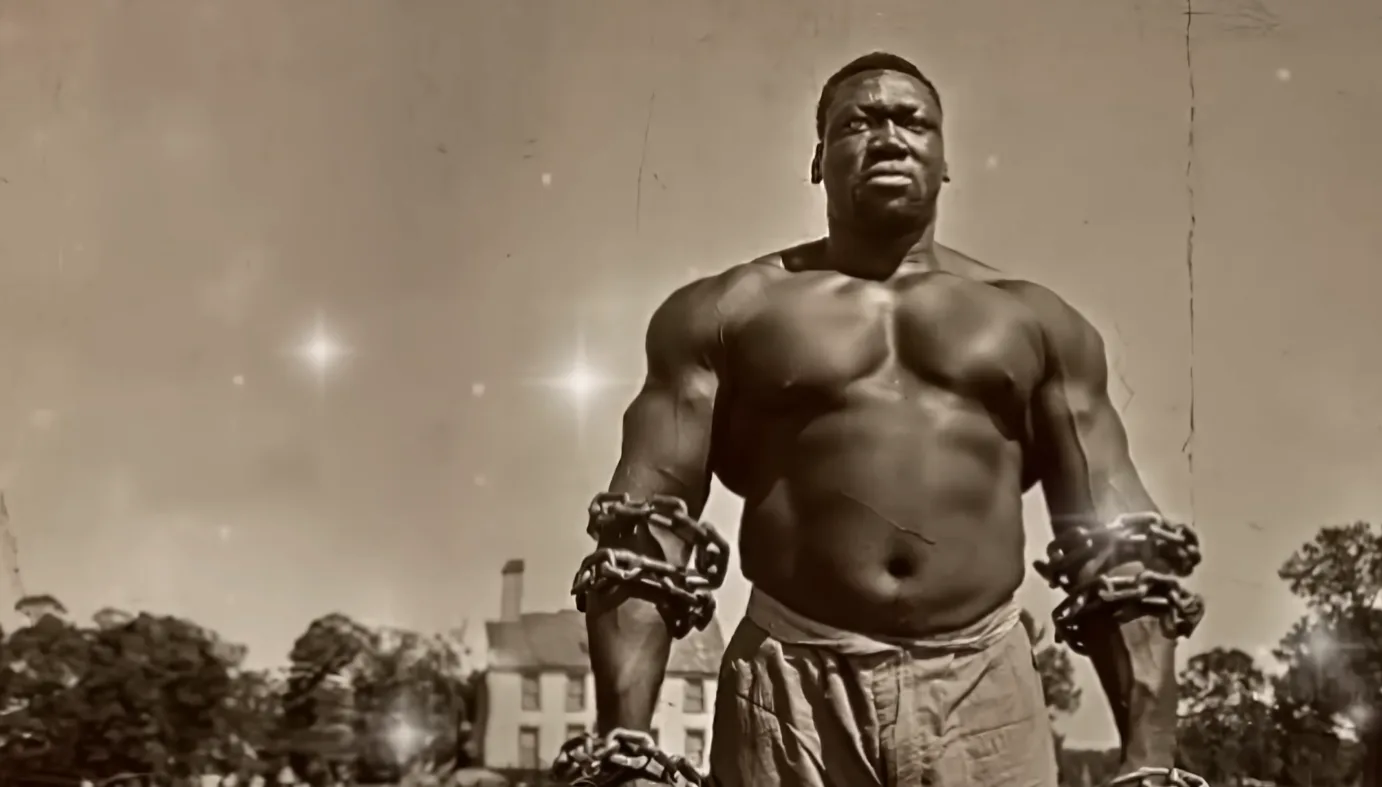

They called him Goliath. Seven feet six. A frame so large it made doorways feel too small and grown men feel suddenly unsure of themselves. For years, he had carried loads that should have taken teams. For years, he had endured humiliations meant to turn him into a warning: look, this is what happens when power owns you.

And then, on one October night, Halifax County learned a different kind of lesson—one about what happens when a person decides they will not be reduced any further, no matter the cost.

To understand how the plantation descended into that night, you have to understand how Cornelius Blackwood made a human being into an “investment,” and how that investment eventually turned into a reckoning.

The auction block in Richmond, Virginia. September 1841.

Cornelius Blackwood arrived looking for field hands—strong backs for tobacco in Halifax County. What he found, instead, was something he had never seen in decades of buying and selling people.

A boy, maybe fifteen, already towering. But it wasn’t just height. It was proportion: arms that fell long, hands that looked oversized even from a distance, shoulders that seemed built for carrying the impossible. The auctioneer’s voice grew theatrical as he spoke, as if introducing a rare animal.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “a specimen unlike any you’ll see again.”

Cornelius pushed closer. Up close, the boy’s eyes were what unsettled him most—steady, intelligent, taking in every face. Not the empty stare Cornelius preferred. Not the look of someone already broken.

“Can he work?” Cornelius called.

The answer was delivered like a sales pitch: claims of strength, endurance, and usefulness. The price rose fast. Astronomical. Cornelius still bid. He didn’t see a boy. He saw profit.

“Sold,” the auctioneer declared, and Cornelius Blackwood left Richmond with the most expensive purchase of his life—and the certainty that he’d just bought more than labor.

When the boy arrived at Blackwood Plantation, he spoke almost no English. His African name did not fit easily into Cornelius’s mouth, and Cornelius treated that as an inconvenience rather than a loss. So he gave him a new name—one delivered as a joke at the dinner table, to laughter from wife and sons.

“You’re Goliath now,” Cornelius announced. “A giant. Fitting.”

The boy stood silent in the corner of the dining room, nearly touching the ceiling, absorbing the sound of laughter as if it were a language he could understand without translation.

Cornelius’s youngest son, Jacob, tested the boundaries early. A piece of bread tossed at the giant’s feet. A command said with cruelty, not curiosity. The boy didn’t move.

When Jacob raised a hand to “teach” him, Cornelius intervened—not out of mercy, but calculation.

“This one cost me,” he warned. “You damage him, you pay for it.”

That night, chained in a cellar with a ceiling high enough for him to stand, Goliath touched the fresh marks on his skin and remembered Jacob’s sudden hesitation—the small flash of fear that appeared when the giant’s eyes turned toward him.

They should be afraid, he thought, in the language of his childhood. They should be.

Within a month, Cornelius turned his “investment” into a local attraction.

After church on Sundays, men came to Blackwood Plantation like visitors to a show. Cornelius charged admission. He cleared a barn, arranged benches in a semicircle, and built a stage out of humiliation.

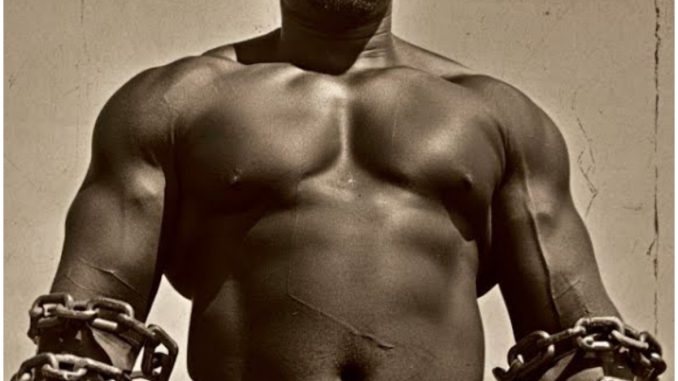

Goliath was brought out in heavy restraints. The audience didn’t see a person. They saw a story they could tell later. Cornelius gave commands and pointed to objects meant to impress: bales, barrels, timber. Goliath lifted what others couldn’t.

The crowd reacted the way crowds do—gasping, laughing, applauding—pretending amazement erased the cruelty that made the moment possible.

Then came the contests.

Cornelius would call for volunteers—overseers, rich sons hungry for attention, men eager to prove something. Three against one. The rules were simple: hands only, surrender ends it. If the three men “won,” they took money. If Goliath “won,” he received a bigger portion of food for the week—as if survival could be used like a prize.

Goliath rarely lost. Not because he enjoyed it, but because he refused to give them the satisfaction of seeing him defeated. He learned patience. He learned timing. He learned how to endure noise and pain without giving the crowd the moment it wanted.

Cornelius would beam afterward, accepting congratulations as if he’d trained a valuable animal.

“Magnificent creature,” he’d say.

Creature. Never man.

But Sunday was only the performance. Monday through Saturday was the grind.

Halifax County tobacco in summer was relentless. Heat that stole breath. Soil that clung to feet. Overseer Thornton watched the fields with a whip and a habit of reminding everyone who controlled time itself.

While others carried what a body could reasonably carry, Goliath carried what a body was never meant to carry. When others paused for water, his break was shorter. When others returned to quarters, he worked longer. At night, he was locked away separately, restraints engineered like a custom-made statement: you are too large to be allowed even the illusion of trust.

For a while, he ate like a machine—because survival required it. Then he began to understand more English, and the words he understood hardened something inside him.

Not just commands. Conversations.

How Cornelius spoke of him like equipment. How the sons spoke of him like a tool. How visitors joked about him as if he were not standing within hearing distance.

Uncle Moses, an older man who had been enslaved for most of his life, watched Goliath the way people watch storms on the horizon.

“That one’s dangerous,” Moses whispered one night. “Not because he’s big. Because he’s quiet.”

Year four brought Dr. Artemis Whitmore.

Whitmore was a physician from Richmond with theories he wanted to “prove,” and he used measurements and examinations to dress prejudice in the clothing of science. When Cornelius mentioned his “giant” at a club, Whitmore insisted on seeing him.

They negotiated a fee.

Whitmore arrived monthly with instruments, notebooks, and the certainty that his curiosity mattered more than another person’s dignity. He measured. He prodded. He recorded. The process was presented as “non-damaging,” but Goliath understood the truth: being treated like a subject instead of a human leaves marks that don’t always show.

Still, he refused to give them the satisfaction of begging.

Behind his flat, steady eyes, pressure built—slow, constant, patient.

Year seven brought Naomi.

She arrived among house servants from an estate sale, small and quick-handed, useful to the big house. The first time Goliath saw her, she was hanging laundry behind the house, humming a tune so familiar it made his chest ache.

A song from home. A song he thought the ocean had swallowed.

He took an unnecessary route past the laundry lines. Close enough to be seen. Naomi paused, looked up, and for a moment the plantation disappeared.

“You know that song,” he said, voice rough from disuse.

She nodded. “My grandmother taught me. Said it came from the homeland.”

“It does,” he answered, and in that brief exchange, something returned to him that had been absent for years: not softness, exactly—something sharper. Meaning.

They met when they could. In quiet corners. In minutes stolen from chores. Naomi helped him with English—not just words, but understanding. The kind that let him hear what people said when they assumed no one “like him” truly comprehended it.

In return, he told her about the homeland: names of things, the way the sky looked, the stories that kept a person human when everything around them insisted otherwise.

One evening, Naomi asked, amazed, “You remember it all?”

“I remember every second,” he said. “I hold the memories like weapons.”

In 1853, Cornelius agreed to let them live together in a small cabin behind the quarters. It wasn’t kindness. It was calculation—another way to increase “value.” Still, for the first time in twelve years, Goliath slept without restraints, Naomi pressed against him, and the cabin felt like the closest thing to freedom he had ever touched.

He should have known it couldn’t last.

In 1856, Naomi became pregnant. For a short while they kept it quiet, but secrets rarely survive under a house that treats people like inventory. When the news reached Cornelius, his smile was not one of joy. It was the smile of someone imagining profit.

Then Marcus Doyle arrived—a trader who specialized in “specialty merchandise,” the kind of phrase that turns people into objects with price tags.

Over cigars and whiskey, Doyle explained the market for pregnant women, the way buyers in far-off cities paid extra for “curiosities,” the way a pregnancy could be treated like an experiment.

Cornelius listened, weighed numbers, and decided.

That night he found Goliath working in the barn.

“I’ve sold your wife,” Cornelius said, as casually as if he were discussing tobacco.

The words didn’t land like words. They landed like a door slamming shut.

Overseer Thornton brought the heavy restraints again—not because Cornelius feared violence as a moral problem, but because he feared damage to his property.

Naomi was allowed a brief goodbye. In the barn, she pressed a scrap of cloth into Goliath’s hand, the only thing she could give that belonged to her.

“Remember me,” she whispered.

When she was taken away, the barn felt too quiet. Goliath stood there holding that cloth, and something inside him—something bent for years—finally broke.

A week later, he returned to the fields. Outwardly obedient. Inwardly awake.

For the first time, he saw the plantation as a map. The blacksmith shop. The tools. The routines. The habits of men who believed power made them untouchable. He remembered the kitchen door that stayed open late. He noticed the creaking floorboards. He learned who slept where, who drank too much, who grew careless.

He wasn’t imagining survival anymore.

He was planning justice.

He built trust quietly. Uncle Moses confirmed who could be relied on. Josiah the blacksmith hid items that could become weapons. Ruth the midwife gathered herbs with knowledge older than any rule. Rebecca, trusted inside the house, listened to secrets the masters spoke as if servants were furniture.

Goliath made one thing clear: this wasn’t simply an escape.

This was a settling of accounts with the people who had treated Naomi’s life like a transaction.

They chose October 23, the harvest celebration, because the house would be distracted and careless.

But fate moved first.

Marcus Doyle returned early—October 21. And with him came “news.”

Goliath positioned himself close enough to hear through open windows.

Doyle spoke about Naomi and the baby in the same tone he used for business. The words landed, and the world narrowed. Whatever hope Goliath had forced himself to carry—whatever future he’d dared to imagine—collapsed into a single, unbearable truth.

Overseer Thornton ordered him back to work.

Goliath turned, and Thornton saw the change in his eyes. Not wildness. Not confusion.

Clarity.

What happened next moved quickly, too quickly for anyone to stop. The plantation erupted in shouting. Doors slammed. People ran. The big house became a storm of panic. The men who had always relied on control discovered, all at once, how fragile control really is when the people beneath it stop obeying.

By morning, eight people were gone. The Blackwood household, as it had existed, was finished. The plantation—built on the idea that human lives could be owned—had collapsed into its own consequences.

The enslaved people did not wait for permission to breathe.

They left.

Under cover of night, dozens fled north toward the Blue Ridge, guided by Moses’s knowledge of roads and safe places. They traveled hard, hiding by day, moving by night, carrying little but the will to keep going.

They lost some along the way. Fear and hunger do that. Patrols do that. The world is not gentle to people running for their lives.

But many made it.

In the mountains, they found others—communities built in hidden places where freedom existed not as a law, but as a daily act of defiance. And there, Goliath lived not as a spectacle, not as a “creature,” but as a man among people who knew his name was not a joke.

Stories spread, as stories always do. Each retelling made him larger, made the night more dramatic, made the numbers climb. Goliath didn’t correct anyone. Legends have a purpose. They travel farther than facts.

And the legend carried a message the South could not erase: the system depended on obedience, and obedience was not guaranteed.

Years later, armed men finally found the mountain community.

They expected surrender. They expected fear. They expected a quiet ending they could use as a warning.

What they met was resistance—people who had already decided that living without dignity was not living.

Goliath walked out to meet them because he understood something simple: if they were going to chase freedom, someone had to buy time.

When it was over, they displayed his body as proof. They wanted his story to shrink into a lesson about punishment.

Instead, it became a lesson about cost.

Because the people who heard what happened did not only hear “he died.” They heard “he refused.” They heard “he stood.” They heard “chains can break.”

Halifax County, in official records, called it an “incident” and listed “property damage” as if human beings had ever been property at all. But in Black communities, the story survived the way truth often survives—through voices, through memory, through songs that don’t require paper to last.

And that is why his name endured.

They called him Goliath, meaning the giant who falls.

But the part of him that mattered never fell—not really.

Because even now, long after the tobacco fields and the auction blocks, the story still carries the same message into new ears:

You can cage the body.

You cannot chain the soul.

And the moment a soul decides it will be free—truly, completely free—there is no power on earth that can make that decision harmless.