Bumpy Johnson’s Grandmother, a Small-Town Incident, and the Night Greenwood Changed Forever

Thursday, July 18th, 1946. Greenwood, South Carolina. 2:15 p.m.

Margaret “Maggie” Johnson was seventy-three years old when she walked down Main Street with a small bag of groceries from Miller’s General Store. She moved slowly, leaning on an old wooden cane that had belonged to her late husband. In a town like Greenwood, her pace was unremarkable—an elderly woman doing what elderly women did: getting what she needed, keeping her head down, and trying to make it home before the heat pressed too hard against her lungs.

Maggie had lived in Greenwood her entire life. Born in 1873, she had seen the world change in loud ways and stay the same in quiet ones. She had outlived Reconstruction, outlived the Depression, outlived two wars, and outlived most of the people who once knew her as a young mother with a house full of children. Widowed since 1929, she lived in a small home on Cedar Street, a place that carried decades of family history in its walls.

She was not known as an organizer. Not known as an agitator. She wasn’t someone who stood on street corners or attended public meetings. In 1946 South Carolina, being visible could be dangerous—especially if you were Black. Maggie had learned the old rule that so many people learned: survive by staying small.

But Maggie had one connection that made her anything but small.

She was the grandmother of Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson—already feared in Harlem, already spoken about in whispers, already connected to power that reached beyond city blocks and state lines. In Greenwood, some people knew. Many didn’t. Maggie herself rarely spoke about it in public, except on rare occasions when pride slipped out the way it does when you’ve raised someone with your own hands.

After her daughter—Bumpy’s mother—died in 1916, Maggie helped raise the boy. She watched him grow from bright and restless into someone the world would later describe with darker words. Whatever he became, she loved him. And he, in return, treated her as sacred.

To him, she wasn’t a chapter in a biography. She was home.

That was why what happened at 2:23 p.m. mattered more than anyone on Main Street could have understood.

As Maggie passed near the Greenwood Women’s Social Club, she accidentally bumped into Eleanor Pritchard, a white woman in her early fifties—well-known, well-connected, and married to a deputy sheriff. The collision was minor, the kind that happens in crowded places when someone turns at the same moment another person steps forward.

Maggie immediately apologized. She did it with the careful tone that older Black Southerners had learned could sometimes protect them. She kept her eyes low. She used polite words. She tried to move on.

But Eleanor Pritchard didn’t accept the apology.

Instead, she raised her voice—loud enough for people to stop and look, loud enough to turn a small mistake into a public scene. The point wasn’t the bump. The point was the reminder. The point was power.

Within seconds, three other women stepped in. Not strangers—women tied to important families in town, women who moved through Greenwood with confidence and assumption, the kind that came from knowing how the local system worked and who it worked for.

They surrounded Maggie.

In another era, in another place, a group of adults surrounding an elderly woman would have drawn immediate intervention. But Greenwood was not that kind of place in 1946. People looked, then looked away. They recognized the danger of being the person who “got involved.”

What happened next unfolded quickly, partly because it didn’t need planning. It ran on something older than planning.

The women dragged Maggie away from open view and into a side alley, where Main Street noise dulled into distance. Maggie cried. She tried to explain. She tried to appeal to basic decency.

But decency wasn’t what the moment was built on.

Minutes passed. A commotion carried through the alley, and a Black worker named Thomas Washington—on a break behind a hardware store—heard it and stepped toward the sound. When he saw what was happening, instinct pulled him forward, the way it does when you see someone vulnerable being harmed.

Then a voice snapped at him, sharp and threatening, warning him to stay back.

Thomas froze.

He later described it like being trapped in a rule he hadn’t written but had always known. In that moment, he wasn’t just weighing his own safety. He was thinking about the price other people could be forced to pay because of what he did. In places like Greenwood at that time, consequences didn’t stop with one person.

So he did the hardest thing: he didn’t move.

Not because he didn’t care, but because fear had been engineered into the air.

When it was over, the alley fell into a silence that didn’t feel peaceful. It felt emptied. What was left behind was grief, shock, and a sense of something irreversible—because in that era, an elderly Black woman could be harmed and the town’s official machinery could treat it as background noise.

The women returned to their day as if nothing meaningful had happened.

And that is the detail that would later sit like a stone in the stomach of everyone who heard the story: the ease. The normalcy afterward.

At 3:15 p.m., Thomas Washington did something brave.

He walked to a Black-owned barbershop and used a phone to make a long-distance call to New York City. He did not know Bumpy Johnson personally. He did not know what this would unleash. But he knew one thing clearly: whatever Greenwood’s systems did next, they would not bring comfort or accountability. If anything happened at all, it would have to come from outside.

The call took time—operators, transfers, the slow mechanical patience of 1940s long-distance lines. Eventually, Thomas reached a man connected to Harlem’s underworld: Marcus Webb, a trusted figure in Bumpy’s circle.

Thomas spoke quickly and carefully. He shared what he knew: the names, the relationships, the public standing of the women involved, and the fact that they moved through town without fear. He spoke as if every second mattered—because he believed it did.

Marcus Webb’s voice, Thomas later recalled, was calm in a way that didn’t feel reassuring. It felt controlled.

He told Thomas to stay near the phone and say nothing else to anyone.

Then he hung up.

By the time Marcus called Bumpy, Harlem was still running on its usual rhythm—street corners, club doors, late-afternoon heat rising off pavement. Bumpy, at that hour, was reportedly at home. A normal moment, until the phone turned it into something else.

When Marcus delivered the news, Bumpy didn’t speak right away.

People who knew him described that kind of silence as dangerous—not because it was loud, but because it meant the decision had already been made internally. The emotion had already been compressed into something hard.

Bumpy asked for names.

He wrote them down.

Then he gave an instruction that wasn’t about a courtroom, or a sheriff, or a legal process. It was about consequences—swift ones, the kind that Jim Crow society had long reserved for Black families, but rarely feared in reverse.

What followed that night was not public in the way official history likes stories to be. It was not printed in polite newspapers with full details. It moved through the town as rumor first—whispers that something had happened, that something had shifted, that power had reached Greenwood in a form the town hadn’t expected.

By morning, Greenwood woke to a scene that unsettled people not only because of what it implied, but because it shattered a long-standing assumption: that violence could be one-directional and remain safe for the people who practiced it.

Law enforcement arrived, then hesitated.

Not every hesitation comes from kindness. Sometimes hesitation comes from calculation. When the people involved are connected to influence, and when the consequences are larger than a single arrest, institutions become careful. They choose what not to see. They choose what not to name out loud.

And Greenwood’s white establishment, so confident the day before, began to feel something unfamiliar—uncertainty.

In Black neighborhoods, the emotions were different and complicated. There was grief. There was fear. There was also the exhausting recognition that even when something looks like “balance,” it still doesn’t restore what was taken. Nothing restored Maggie Johnson.

Nothing gave her years back.

Nothing reversed the moment when an old woman carrying groceries became a symbol—first of cruelty, then of escalation.

In the days that followed, the story traveled far beyond Greenwood. It moved the way warnings move: not as a moral lesson, but as a practical one. In towns across the region, people began speaking more carefully about what it meant to target someone who had connections to money and influence beyond the county line.

It was the kind of shift that doesn’t make official archives, but changes behavior anyway.

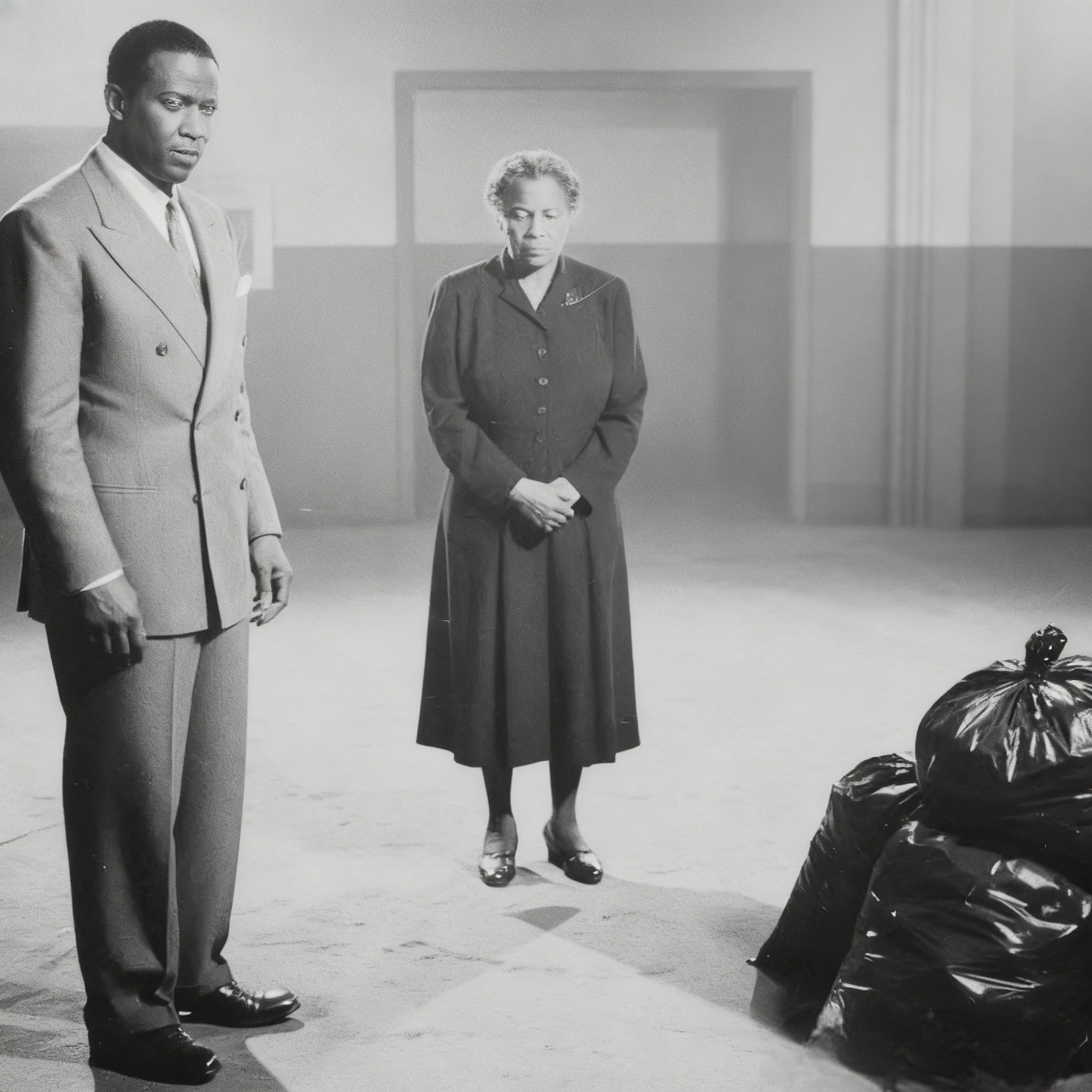

Later, those close to Bumpy would describe his grief as private and steady. He did not turn the loss into speeches. He did not turn it into public performance. He attended the burial and stood quietly, dressed in black, watching a casket lowered into Southern soil that had never been gentle to families like his.

If anyone expected him to look satisfied, they didn’t understand the nature of loss.

When you lose the person who raised you, “winning” is not part of the vocabulary.

The only thing left is a promise: that the world will not treat their name as disposable.

Greenwood never fully forgot that week. Not because it became a celebrated legend, but because it became an unspoken boundary. It reminded people that power doesn’t always wear the same uniform—and that consequences can come from places the local order doesn’t control.

And for those who heard Maggie Johnson’s story, the lasting question wasn’t only about what happened that night.

It was about what happened before it.

How a small collision could become a threat. How a town could watch an elderly woman get pulled into an alley and decide safety meant silence. How a system could exist where an old woman’s dignity could be treated as optional.

Maggie Johnson was seventy-three years old. She wasn’t an activist. She wasn’t a fighter in the public way people like to romanticize later. She was a grandmother. A widow. A woman trying to get home with groceries.

And yet, in death, she became a marker of something the country still wrestles with: the cost of living in a place where dignity depends on someone else’s permission—and what happens when that permission is denied.