In 1863, America was tearing itself apart.

Cannons thundered across battlefields. Towns changed hands. Families argued about loyalty, liberty, and what the nation was willing to become.

image

But far from the noise of war, another conflict had been unfolding for generations—quiet, systematic, and designed to leave as little proof as possible.

On a Louisiana plantation, an enslaved American man named Gordon lived inside that hidden war.

He was born into a world that never planned to remember him.

No verified record of his childhood survives.

No official document tells us who his parents were, what day he was born, or what he might have hoped for when he was young.

That blank space was not a mistake.

Enslaved people were not expected to have personal histories that mattered to the public record. They were expected to produce profit, follow orders, and vanish when their bodies could no longer endure the workload.

Gordon existed in ledgers as labor.

And in daily life, he existed inside a system that turned human beings into property and made suffering feel ordinary by repeating it until everyone stopped reacting.

The plantation itself ran on structure.

Fields were divided and measured.

Work was timed and supervised.

Rules were enforced with rituals that were meant to teach fear as efficiently as any classroom taught reading.

What Gordon endured was not random cruelty. It was policy, reinforced by routine.

It was a method designed to keep thousands of people in place—not only by controlling their bodies, but by controlling their belief in what was possible.

By the time the Civil War reached its third year, the sound of change drifted even into places that tried to shut it out.

Rumors traveled the way rumors always do: quietly, person to person, through brief exchanges and careful whispers.

On paper, freedom had been declared in parts of the country.

In reality, on plantations like Gordon’s, the daily machinery continued.

Overseers still watched.

Work still began before the sun had fully settled into the sky.

Punishment still existed as a warning, not only to the person targeted, but to everyone made to witness it.

The system functioned as if history could be kept outside the gates.

For Gordon, staying meant the same thing it meant for so many others: being gradually erased.

Leaving meant risk—capture, severe retaliation, or death.

Escape from a Louisiana plantation was not a cinematic act. It was a decision made under pressure, usually in silence, often without help.

The land itself could destroy you if you moved carelessly.

Swamps swallowed footprints and sometimes swallowed people.

Patrols searched roads and tree lines.

Dogs were trained to follow scent, turning forests into traps.

Hunger and exhaustion could make a person collapse long before they reached safety.

Most who attempted to leave did not succeed.

Gordon ran anyway.

He moved through water and darkness, guided not by certainty but by stubborn resolve.

Each step forward carried danger.

Each unexpected sound could change everything.

But behind him was a life designed to grind his identity down into nothing—day after day—until he stopped imagining himself as a person with choices.

Forward, at least, offered a possibility that slavery worked hard to eliminate: the chance to be seen as human.

When Gordon reached Union lines, he did not arrive as a symbol.

He arrived as a man—exhausted, injured, and alive.

To the soldiers who encountered him, he was one of many people fleeing plantations as the war shifted power across the South. They had seen hunger. They had seen fear. They had seen bodies worn thin by forced labor.

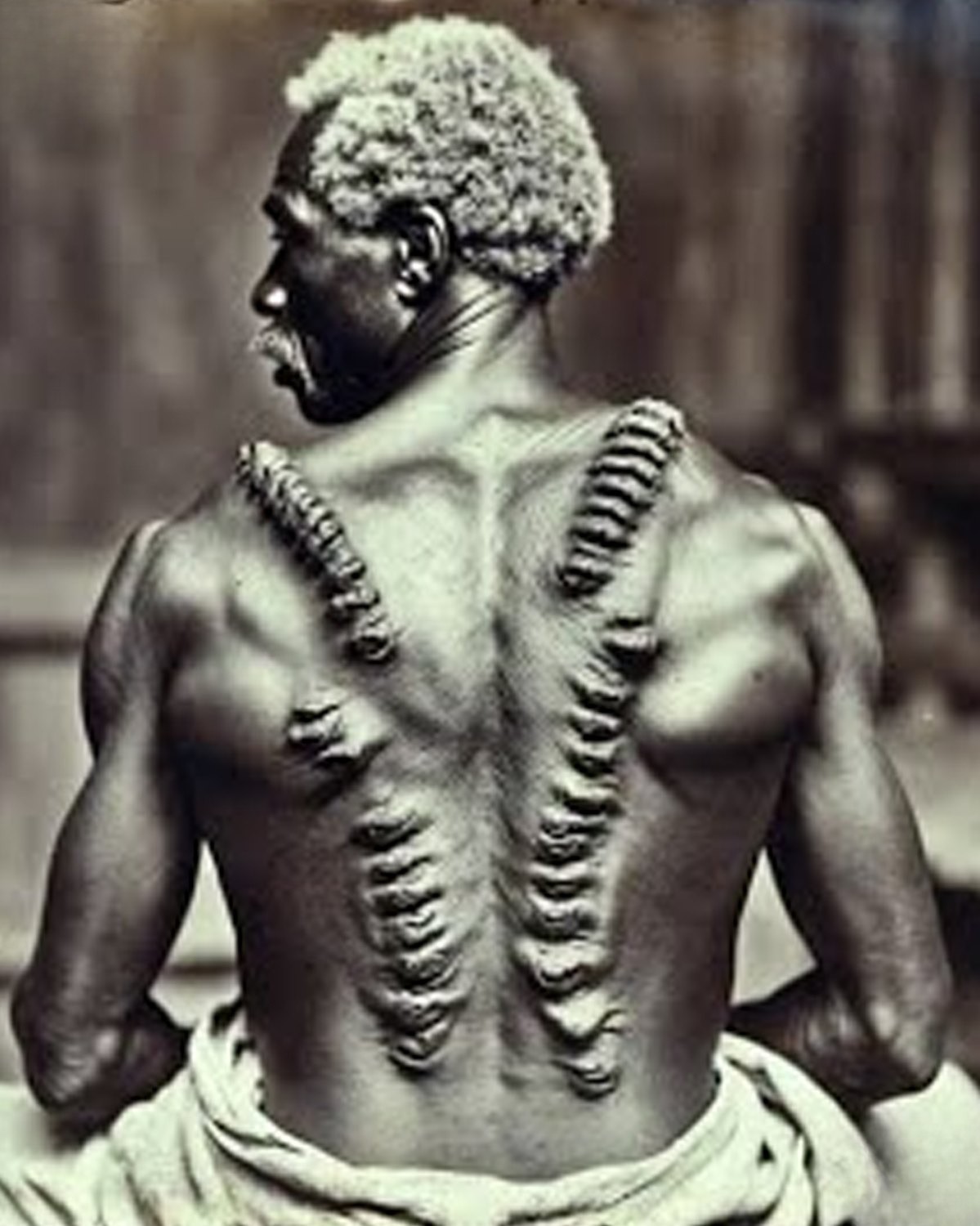

But when medical staff examined Gordon, they went quiet.

His back carried evidence.

Not the kind of evidence that could be debated in speeches or softened into polite language, but the kind that sat in plain sight and refused to be explained away.

It was not a single mark or a fresh injury that could be dismissed as an incident.

It suggested repetition.

It suggested a pattern.

It suggested years of discipline enforced through force—administered under authority, accepted as normal, and sustained by a society that insisted this was all “managed” and “orderly.”

Someone decided to document what they saw.

The photograph that followed was simple and devastating.

No dramatic pose.

No props.

No staged scene meant to tell viewers what to think.

Just Gordon, seated, his back turned toward the camera.

The image didn’t argue.

It didn’t editorialize.

It presented proof.

And that was exactly why it landed with such impact.

When the photograph circulated in the North, it disrupted the comfortable distance many people had maintained.

Slavery had been debated for decades as an institution, a political compromise, an economic necessity, a “regional issue.”

Politicians argued with speeches.

Newspapers filled pages with justification and denial.

Owners and their allies defended the system with polished language, insisting it was stable, controlled, even humane.

Gordon ended that rhetorical shelter without speaking a single word.

People who had never stepped onto a plantation could no longer pretend they were only debating theory.

The photograph bypassed abstraction and struck conscience directly.

It forced viewers to confront consequences, not concepts.

It suggested that slavery was not a minor flaw in an otherwise civilized society.

It was a structure that depended on coercion and sustained harm to function.

The reaction was immediate.

Abolitionists shared the image as undeniable evidence.

Ministers referenced it from pulpits, not as sensational material, but as moral testimony.

Homes that had treated slavery as distant politics suddenly fell silent before the photograph.

For some, it hardened resolve to push the war toward a decisive end.

For others, it produced an uncomfortable recognition: neutrality was not an innocent position when the truth was this visible.

In the South, where the photograph appeared at all, the response was defensive.

Some dismissed it as propaganda.

Some claimed it reflected “discipline” that was supposedly deserved.

Others tried to narrow the story into an exception—one harsh incident that did not represent the whole system.

But those reactions revealed something important.

If Gordon’s suffering was acknowledged as unjust, then the moral foundation of slavery collapsed.

So the image was attacked—not only to protect reputations, but to protect the lie itself.

Meanwhile, Gordon did not remain frozen in the moment of documentation.

After reaching safety, he joined the United States Colored Troops.

That decision matters.

The same nation that had allowed him to be enslaved now handed him a uniform.

And that uniform did not erase injustice. Black soldiers faced discrimination, unequal treatment, and dangerous assignments. Freedom did not arrive cleanly or generously.

But service offered something slavery refused to allow: agency.

Gordon was no longer only a person who had survived what was done to him.

He became someone who chose his next step.

That transformation threatened the entire logic of slavery.

Gordon was no longer only evidence of cruelty.

He was evidence of capability.

He contradicted another lie—that enslaved people were inferior, dependent, or unable to live freely.

His very presence in a uniform challenged the story the system had built to justify itself.

Yet as his photograph traveled, something else happened—something quieter, but equally revealing.

The image endured.

The man faded.

Gordon became known primarily as “the man with the scarred back.”

His individuality slowly dissolved into symbolism.

Textbooks reproduced the photograph.

Lectures referenced it.

Newspapers recalled it in passing.

The nation remembered the evidence while forgetting the complexity of the person.

This was not accidental.

Symbols are easier than people.

A symbol can be displayed without changing anything.

A symbol can be honored while systems remain intact.

A person demands recognition, context, and responsibility.

America preserved Gordon’s suffering as proof of a past wrong while often neglecting the life he tried to build afterward.

After the war, slavery ended in law but not in structure.

Reconstruction promised transformation and delivered fragility.

New systems emerged to keep control in place—through economics, biased enforcement, intimidation, and laws written to limit who could truly participate in freedom.

Gordon’s photograph remained in archives while the urgency it once created began to fade.

Exposure disrupted a lie.

But exposure alone did not dismantle the machinery that depended on it.

Over time, the image grew familiar.

What once shocked began to instruct.

Gordon’s back was taught as a lesson about how slavery was wrong—yet often framed as if the problem was finished, sealed in the past, resolved by legislation and victory.

The photograph became a punctuation mark in history rather than a challenge to the present.

And still, it never lost its power entirely.

Each generation that encounters it faces the same quiet test.

What does it mean to see undeniable evidence of injustice?

Is recognition enough?

Is remembering enough?

Or does memory require action—then and now?

Gordon never wrote a memoir, at least none that survived.

He did not control how his story was told.

But in one moment in 1863, his presence cracked America’s greatest lie—that slavery was gentle, benign, or necessary.

His body exposed not just cruelty, but deception.

It revealed how deeply the nation had invested in pretending suffering could be managed into invisibility.

And once that truth was seen, it could not be unseen.

Gordon asked for freedom.

What he gave the country instead was something that injustice fears even more than anger.

He gave proof.

And proof, once revealed, never truly disappears.