The White House and the Labor History America Long Overlooked

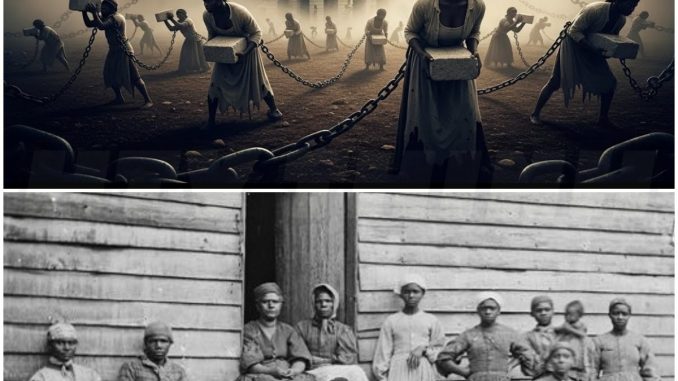

Between 1792 and 1800, a building rose from marshy land along the Potomac River that would become one of the most recognizable symbols in the world: the White House. It is often described as a triumph of early American architecture, vision, and ambition. Yet for generations, one essential part of that story remained incomplete.

The White House was constructed in significant part by enslaved labor.

This fact is no longer disputed by historians. Payroll records, correspondence, and government documents confirm that hundreds of enslaved men—and some women—were hired out by their owners to work on the president’s house and other federal buildings in the new capital. What has taken far longer to acknowledge is what that work truly meant: the conditions, the human cost, and the deliberate absence of these workers from the nation’s early historical narrative.

A Capital Built on Unfinished Ideals

In 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, establishing a new federal district carved from land ceded by Maryland and Virginia. President George Washington personally selected the site in 1791. The location that would become Washington, D.C. was far from pristine. It consisted of swampy terrain, dense woods, and farmland long worked by enslaved people.

The young republic faced a serious problem: it lacked money. The federal government was burdened by Revolutionary War debt and had limited resources to build monumental structures. To solve this, officials turned to a practice already common in the region—renting enslaved laborers from local plantation owners.

Owners were paid a monthly fee. The laborers themselves received no wages and had no choice in the matter.

Who Built the President’s House?

Government payment ledgers from the 1790s list dozens of enslaved workers hired from nearby counties in Maryland and Virginia. The records name plantation owners in detail, while the laborers are often identified only by first name, age, or generic labels such as “laborer” or “boy.”

These workers performed some of the hardest and most dangerous tasks:

- Clearing forests and draining swamp land

- Excavating foundations

- Quarrying and transporting sandstone from Aquia Creek

- Brickmaking and heavy lifting

- Carpentry and interior finishing

Skilled enslaved craftsmen—stonecutters, carpenters, and masons—were especially valuable to the project. Their expertise was essential, yet their identities were rarely preserved in official documents.

Conditions on the Construction Site

The environment was harsh. Summers in the Potomac lowlands were hot, humid, and filled with insects. Winters were cold and muddy. Temporary housing offered little protection from the elements, and food provisions were basic and minimal.

Surviving correspondence between project commissioners frequently refers to “sickness among the laborers,” but almost always in relation to construction delays rather than human suffering. When enslaved workers became too ill to work, they were often sent back to their owners and replaced. What happened afterward was usually not recorded.

Medical care existed, but it was limited and uneven. Records show that physicians were compensated differently depending on whether they treated free or enslaved workers, reflecting broader inequalities of the time.

Disappearing Names and Silent Records

One of the most troubling patterns in the documents is the sudden disappearance of individuals from payment lists. A name might appear for months or years, then vanish without explanation. In some cases, the owner continued receiving payment for other workers, suggesting replacement rather than recovery.

Historians caution against drawing conclusions without definitive proof. Record-keeping in the 18th century was inconsistent, and not every absence indicates death. However, the frequency of unexplained substitutions and the volume of replacement requests—especially during periods of extreme weather—strongly suggest that serious illness and fatal accidents occurred.

What is clear is that no comprehensive effort was made to document the outcomes for enslaved laborers who could no longer work.

The Question of Unmarked Burials

Over the years, stories circulated within Washington’s Black communities about workers who died during construction and were buried without markers. These accounts were passed down orally, generation to generation, long before scholars began examining archival evidence.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, renovations to the White House reportedly uncovered human remains near foundation areas. Contemporary supervisors chose to handle such findings quietly, prioritizing continuity of work and institutional stability. No formal investigations followed, and no public acknowledgment was made at the time.

Modern historians urge caution. Without archaeological excavation and forensic study, it is impossible to determine identity, cause of death, or connection to White House construction. What these discoveries do demonstrate is how consistently uncomfortable findings were set aside rather than explored.

Names Carved Where History Could Not Erase Them

During renovations in the early 1900s, workers removing interior plaster reportedly noticed carved markings on stone blocks—initials and names turned inward during original construction. These markings were consistent with practices seen at other historic building sites, where laborers left personal marks on materials they shaped.

At the time, supervisors ordered the stones covered again. No official record was filed.

Today, historians interpret these carvings as acts of quiet resistance and self-recognition. In a system that denied enslaved people legal identity, carving a name into stone was a way of asserting existence: I was here. I built this.

Official History and Strategic Silence

When the White House was completed in 1800 and first occupied by John Adams, official reports praised architectural design, cost management, and leadership. Enslaved labor was barely mentioned.

When Thomas Jefferson moved in the following year, he brought enslaved workers from Monticello to serve in the household. At the time, this was viewed as normal rather than contradictory, even as Jefferson wrote extensively about liberty and self-government.

Throughout the 19th century, guidebooks and public histories described the White House as the product of skilled labor and enlightened planning. When enslaved workers were acknowledged at all, they were described with vague, euphemistic language that softened the reality of coercion.

This was not accidental. It reflected a broader national tendency to celebrate founding ideals while minimizing the systems that contradicted them.

What Modern Scholarship Confirms

Today, institutions including the White House Historical Association and the National Park Service openly acknowledge the role of enslaved labor in constructing the executive mansion and other federal buildings.

What remains debated is the precise human cost. Estimates of deaths vary, and responsible historians emphasize evidence over speculation. What is beyond dispute is that:

- Enslaved labor was essential to construction

- Working conditions were physically demanding and hazardous

- Record-keeping prioritized property and budgets over people

- Many individual stories were lost by design, not accident

Why This History Matters Now

Recognizing this history does not diminish the White House as a national symbol. It deepens its meaning.

The building stands not only as a seat of government, but also as a reminder of the contradictions embedded in America’s founding: liberty alongside bondage, ideals alongside exclusion. Understanding who built the White House—and under what conditions—forces a more honest reckoning with the past.

The men and women whose labor shaped its walls were not anonymous hands. They were people with names, families, skills, and hopes. Some left marks in stone. Others left only gaps in the records.

History did not forget them by chance. It forgot them through silence.

Telling this story now is not about assigning modern judgment to the past. It is about completing the record—and finally acknowledging those who were there all along.