When Rome Won, Women Became “Spoils”: The Part of Conquest Textbooks Avoid

Rome had prevailed, and the legions returned as they always did—disciplined, gleaming, unstoppable.

If you stood along a dust-choked road two thousand years ago, you might have seen banners snapping in the wind, armor flashing beneath the sun, soldiers marching in perfect formation toward the city gates. You would have heard the crowds before you saw them. Victory had a sound in Rome: cheers, drums, chanting, the roar of a population trained to treat conquest as proof of destiny.

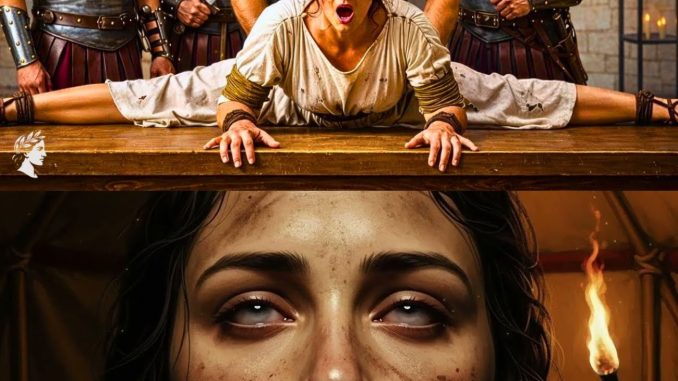

But woven into that pageantry was another procession—one far less celebrated and far more revealing.

Captives.

Not simply prisoners in the modern sense, but human beings transformed by war into property. Women, in particular, were dragged behind the triumphal narrative like a shadow Rome never liked to name out loud. They appeared in the margins of official accounts and in the cold language of administration: “distribution,” “allocation,” “transfer.”

Words that sounded orderly—until you asked what they meant in a world where the defeated had no legal personhood.

Modern culture often prefers a cleaner Rome. We praise aqueducts, roads, and law. We admire the Republic’s ideals and the Empire’s engineering. We watch films where battles end with heroic speeches and clear moral lines.

But Rome’s expansion was not a series of isolated conflicts. It was a machine that ran on war as routine. And where war is routine, what happens to captives is not an accident of chaos. It becomes a system.

Conquest Was a Process, Not a Moment

When a city fell in the ancient world, the violence didn’t end when the gates broke. The fall was only the beginning of a procedure.

Roman campaigns commonly moved through stages that were as practical as they were ruthless. Fighting-age men were treated as immediate threats. Some were executed. Some were kept for labor. Some were sold. The elderly and the very young could be treated as burdens—people who required food, water, transport, supervision—resources armies never considered unlimited.

Then came the women.

Here, the cruelty is not best understood through graphic description. It is better understood through the logic of the empire. Women were not only labor. They were also symbols—of a defeated community’s vulnerability, of a conquered people’s future being placed under Roman control.

And Rome understood symbolism with terrifying clarity.

Captives were displayed in public because the display was the point. It wasn’t only revenge. It was instruction. It told every province watching, and every rival calculating, that resistance would cost more than land. It would cost dignity.

In modern terms, it was psychological warfare—executed with the confidence of a state that believed victory granted moral license.

The Empire Turned People Into Inventory

Rome’s slave system was not a side effect. It was a foundation.

Conquest created captives. Captives became slaves. Slaves fueled farms, mines, workshops, construction projects, and elite households. That labor created wealth. Wealth paid for more legions. More legions created more conquest.

It was a loop so efficient it could masquerade as civilization.

Once Roman control was secured, captives were processed like supply. They were gathered, restrained, divided into groups, and transported toward markets. In the sources that survive—inscriptions, contracts, estate manuals, letters—people appear as entries rather than lives. Origin becomes a label. Age becomes a price modifier. Health becomes a risk assessment.

The most chilling feature of the system is not how chaotic it was.

It’s how organized it could be.

Rome taxed commerce. Rome regulated trade. Rome kept records. And in many places, the trade in enslaved people sat within that bureaucracy as if it were simply another category of goods moving through ports.

That normalization tells you more than any sensational anecdote. When a society can treat human ownership as routine paperwork, it has crossed a moral line so completely that it no longer recognizes the line existed.

What “Spoils” Really Meant

In Roman culture, war had an economic logic and a social logic. Captives were “spoils,” and spoils were rewards. That framing mattered because it reshaped how ordinary people interpreted what happened after victory.

If prisoners were “spoils,” then their suffering could be justified as entitlement.

If they were “property,” then their humanity became irrelevant to the legal order.

If they were “foreign,” then empathy could be framed as weakness.

This is where women’s experience of captivity often carried a distinct dimension. Women were frequently valued not only for labor but for the ways power could be exercised over them. That power was not always expressed in the same form, but the underlying principle was consistent: captivity meant loss of autonomy—of movement, name, family, body, future.

Even when sources avoid explicit detail—and many do, because elite writers often preferred euphemism—they still reveal the structure: women were absorbed into households, brothels, farms, and temples; they were bought and sold; they were separated from their communities; they were reduced to roles assigned by owners.

And the point was always the same: Rome didn’t simply defeat an enemy’s army. It rearranged an enemy’s society.

The Auction Block and the Death of a Name

The slave market was where the empire’s logic became visible. Here, the victorious converted war into profit in full view of the public.

People were inspected like livestock. Their bodies were treated as evidence of value, not evidence of personhood. Buyers looked for strength, compliance, youth, health—traits that translated into productivity or prestige.

What gets lost in that transaction is the most human detail of all: names.

A captive might be renamed by an owner, reduced to an origin (“the Gaul,” “the Syrian,” “the Briton”), or given a label that served the household rather than the person. The renaming was not cosmetic. It was a psychological tool. It told the captive: you are not who you were. You are what we say you are now.

Rome understood that domination was easier when identity was erased.

“Civilization” That Ran on Dehumanization

Roman writers loved to contrast Rome with “barbarians.” Rome, they argued, brought law where there was chaos. Roads where there were forests. Baths where there was dirt. Language where there was noise.

But conquest exposes the contradiction.

Rome’s “order” relied on the organized stripping away of rights from anyone outside the circle of citizens. The empire could build a legal system admired for centuries while simultaneously allowing vast categories of humans to exist as legal non-persons.

This is not unusual in history. It is almost the rule.

States are often most elegant in their paperwork when they are least moral in their outcomes.

When you read Roman estate manuals discussing “management,” when you see contracts itemizing bodies, when you find inscriptions celebrating victories that included mass enslavement, you begin to understand why textbooks often compress this into one sanitized sentence: “captives were enslaved.”

Because the full meaning of that sentence is uncomfortable.

The Long Shadow: Trauma Without a Record

Another reason the story feels incomplete is that the victims rarely left written testimony in sources we can easily access. Most captives did not write in Latin. Most had no materials. Many lived and died far from anyone who would preserve their words.

So what remains is often an archive created by conquerors: accounts by generals, senators, landowners, officials, and historians whose sympathies were shaped by empire.

That imbalance matters. It means we often see captivity through the eyes of people who had every incentive to describe it as normal.

Yet even within that biased archive, you can detect the cracks. You find moments where a letter hints at shame, where a moralist complains about public cruelty, where a philosopher’s “detached” observation reveals an everyday brutality, where a law’s cold efficiency exposes the harm it enabled.

And you find something else—silence.

Silence, not as evidence that nothing happened, but as evidence that the powerful didn’t consider the suffering worth documenting in human terms.

Why This History Still Matters

It is tempting to place this story safely in the past. To tell ourselves Rome was ancient, and ancient people were different.

But war has always created displaced populations, and displacement has always made the vulnerable more vulnerable. The language changes—“refugees,” “migrants,” “detainees,” “rescued persons,” “relocation”—but the core risk remains: when people lose protection under law, they can be treated as means rather than ends.

Rome’s example matters not because it was uniquely evil, but because it was brutally efficient. It shows how quickly a society can normalize the unthinkable when it is profitable, popular, and wrapped in patriotic myth.

That is the uncomfortable lesson.

Not that Rome was monstrous.

But that Rome was functional.

What We Choose to Remember

We build monuments inspired by Roman columns. We borrow Roman legal language. We admire Roman strategy. We tell children stories about Roman greatness.

And then we skip the parts that complicate admiration.

We avoid discussing what victory meant for the conquered—especially for those whose suffering doesn’t fit neatly into heroic narratives. We call it “enslavement” and move on. We treat the victims as background noise behind the empire’s achievements.

But civilization is not only what a society builds. It is what a society is willing to do to human beings—and still call itself civilized.

Rome’s roads are real. So is Rome’s brutality.

The question is whether we can hold both truths at once.

Because when we refuse to look at the full record, we don’t merely misunderstand the past. We train ourselves to miss the warning signs in the present: the bureaucratic language, the euphemisms, the conversion of people into “problems,” the quiet acceptance of harm as “necessary.”

Rome did not become eternal by accident. It became eternal by organizing power—military, economic, legal, cultural—so effectively that even its cruelties could be filed away under order.

Two thousand years later, the ruins still stand.

So does the lesson.