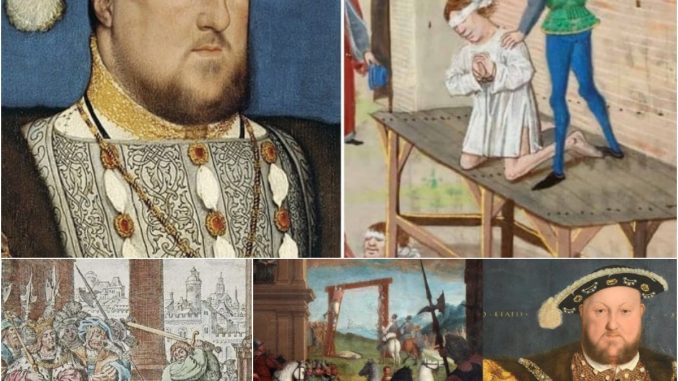

History often remembers the Tudor court through portraits and pageantry: velvet gowns, towering palaces, confident monarchs shaping the destiny of England. What it remembers less comfortably is how fragile human life became when proximity to power turned personal history into a political threat. Few stories illustrate that danger more starkly than the fate of Francis Dereham, a minor gentleman whose earlier relationship with a future queen placed him at the center of one of the most unforgiving moments of Henry VIII’s reign.

Francis Dereham was born around 1513 into a modest gentry family in Norfolk. Like many young men of his background, his future depended not on inheritance alone but on service. The Tudor world functioned through households, patronage, and proximity. Advancement came from being useful, loyal, and discreet. Dereham found employment in the household of Agnes Tilney, Dowager Duchess of Norfolk, one of the most powerful matriarchs in England and a central figure in the Howard family network.

That household was large, crowded, and loosely supervised, especially when it came to young wards. Among them was a teenage girl named Catherine Howard, a relative of the Howards whose upbringing lacked the strict oversight expected of someone destined for prominence. In that environment, youthful familiarity flourished. Boundaries that would later be enforced with severity were, at the time, informal and poorly guarded.

Dereham and Catherine developed a close relationship while both were young. Contemporary accounts describe a level of intimacy that went beyond casual flirtation. They referred to each other using marital language, exchanged small personal gifts, and behaved with a familiarity that drew comment even within a household known for relaxed discipline. Under the religious law of the period, such conduct carried weight. Informal promises, if interpreted as mutual consent to marriage, could be considered binding, even without ceremony.

This relationship ended when Dereham left the Duchess’s household, reportedly traveling to Ireland. Life moved on, as it often did in a society accustomed to abrupt separations. Catherine’s path, however, shifted dramatically. In 1540, she was selected as the fifth wife of Henry VIII. Barely out of adolescence, she was elevated from relative obscurity to queenship almost overnight.

With that elevation came scrutiny. Henry’s court was not simply a political arena; it was a place of relentless observation. Reputation was currency, and rumor could be lethal. The king himself, aging and increasingly anxious about betrayal, had grown intolerant of anything that threatened his authority or dignity. His earlier marriages had ended in public failure, and his patience for perceived disloyalty was gone.

In 1541, whispers about Catherine’s past began to circulate more widely. They reached Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, who faced a dangerous dilemma. To conceal information that might undermine the queen could be interpreted as treason. To reveal it risked unleashing the king’s fury. Cranmer chose disclosure, presenting Henry with allegations that Catherine had been involved with men before her marriage.

In a modern context, such revelations might provoke embarrassment or political negotiation. In Tudor England, they provoked investigation framed as a matter of state security. The question was no longer about youthful behavior. It was about whether the king had been deceived, whether his marriage was invalid, and whether his authority had been compromised.

Francis Dereham was arrested in November 1541. By then, he had returned to court life in a minor role connected to the queen’s household, a decision that would later be interpreted as reckless. He admitted to having had a relationship with Catherine years earlier but denied any improper conduct during her queenship. In another time, that distinction might have mattered. In Henry VIII’s England, it did not.

The legal framework governing the case was expansive and unforgiving. The Treason Act allowed for broad interpretation of any act that could be construed as undermining the crown. Past intimacy, especially if framed as a pre-contract of marriage, could be reclassified as a threat to royal legitimacy. Once the charge moved from moral failing to treason, the outcome became almost predetermined.

Dereham’s social status offered him little protection. He was neither noble enough to warrant leniency nor obscure enough to be ignored. His proximity to the queen made him useful as an example. Alongside another courtier, Thomas Culpeper, Dereham was tried and convicted. The distinction in their sentences reflected the rigid hierarchy of the time. Culpeper, of higher rank and closer royal favor, was granted a less severe punishment. Dereham was not.

On December 10, 1541, Dereham was executed at Tyburn, the traditional site for carrying out sentences imposed on men convicted of treason. Contemporary chroniclers recorded the event as an assertion of royal justice. Modern historians see something different: a demonstration of power intended to erase scandal through fear.

What matters most is not the physical nature of the punishment, which need not be detailed to be understood as severe by the standards of the time. What matters is its purpose. Dereham’s death was meant to restore order, to signal that any perceived challenge to the king’s marriage or masculinity would be met without mercy. It was not simply the end of a life. It was a warning.

Catherine Howard’s fate followed soon after. Stripped of her title and isolated from allies, she was held under guard and later executed in early 1542. She was still a teenager. Her downfall revealed the same brutal logic that consumed Dereham: when royal image was at stake, youth and vulnerability offered no protection.

Together, their stories expose the perilous nature of Tudor court life. Advancement brought visibility. Visibility invited scrutiny. Scrutiny, once it turned hostile, rarely ended in survival. The legal system did not function as a neutral arbiter but as an extension of royal will, shaped by fear, pride, and the need to project absolute authority.

Henry VIII’s reign is often discussed in terms of religious reform and political transformation. Yet beneath those large movements were human lives caught in machinery that had little tolerance for ambiguity. Dereham was not accused of rebellion. He did not plot against the king. He did not seek power. He was a man whose past intersected inconveniently with a woman who later became queen.

That intersection was enough.

Modern examination of Dereham’s case invites reflection rather than spectacle. It forces us to confront how easily law becomes a tool of punishment when unchecked by proportionality or fairness. It highlights how personal relationships, reinterpreted through the lens of power, can be transformed into crimes against the state. And it reminds us that systems built on fear often demand sacrifice not because it is just, but because it is effective.

The Tudor period produced remarkable cultural and political legacies. It also produced victims whose stories challenge romanticized visions of monarchy. Remembering Francis Dereham is not about reliving cruelty. It is about recognizing the human cost of absolute rule and the fragility of life within systems that prize authority over truth.

History does not ask us to judge the past solely by modern standards. It asks us to learn from it. When power becomes personal, when law serves reputation rather than justice, and when individuals are reduced to symbols in a larger narrative, injustice ceases to be an accident.

It becomes inevitable.