In the early 1970s, renovation work at an old courthouse site in central Virginia led to an unexpected discovery. Hidden behind a collapsed interior wall was a sealed metal strongbox containing handwritten notes, correspondence, and early photographs. At first glance, the materials looked like fragments of private record-keeping rather than official government documents. Yet, taken together, they pointed to a pattern that historians had long suspected but rarely been able to document in such detail: the systematic abuse of enslaved women and the legal silence that surrounded it.

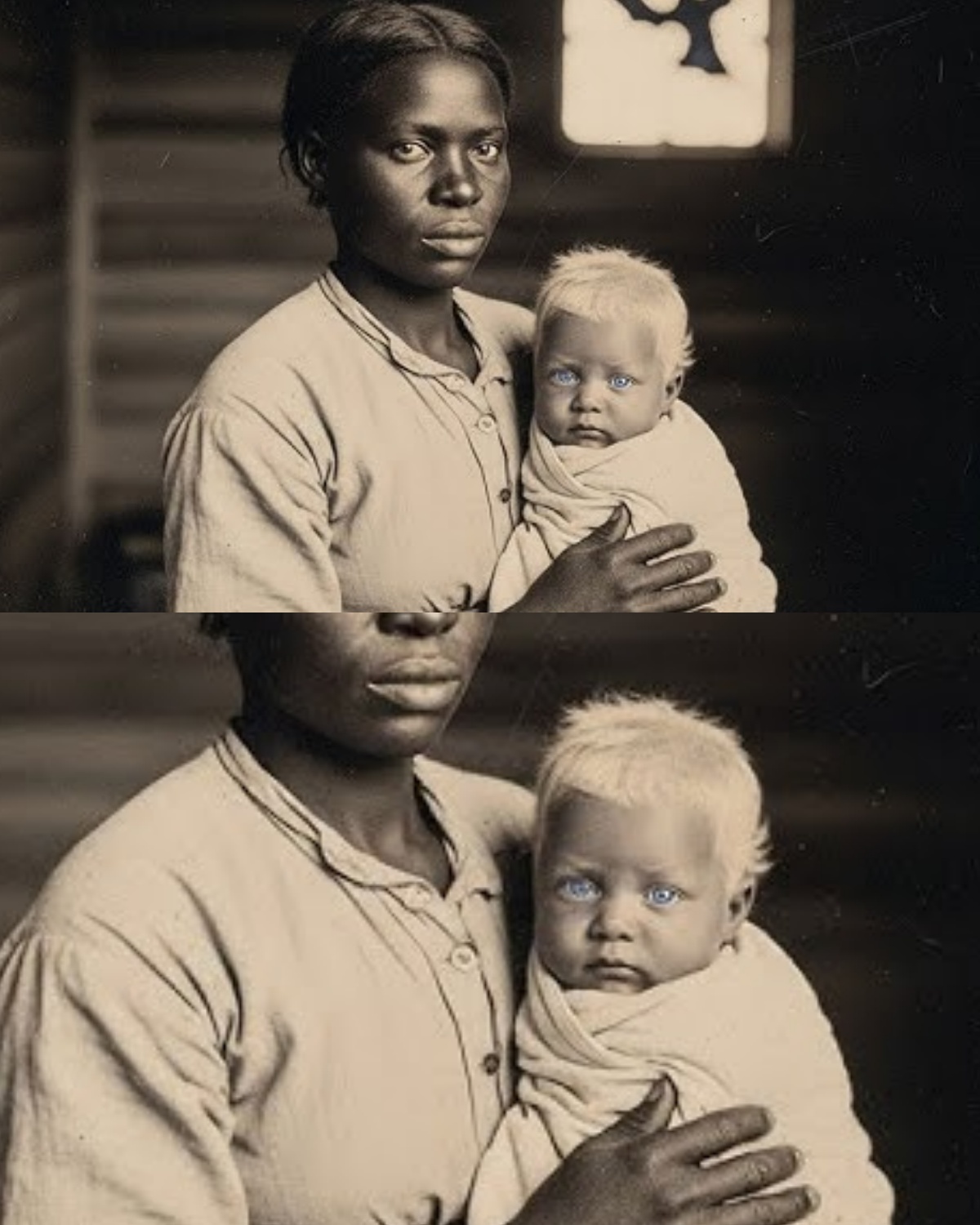

The papers, later studied by scholars at the University of Virginia, focused on a series of births that occurred between 1839 and 1844 in parts of central Virginia. Multiple children were born to enslaved mothers on different plantations, yet contemporaries noted their strikingly similar physical features. These similarities raised questions that plantation society at the time was unwilling—and legally unable—to confront.

This article presents a historical analysis, not a sensational narrative. It examines what the documents show, why the events were possible under antebellum law, and how later historians interpreted the evidence.

The Historical Setting

The events described in the records took place in what is now Henrico County and neighboring areas during the height of the antebellum plantation economy. At the time, Virginia law defined enslaved people as property rather than legal persons. As a result:

-

Enslaved women had no legal standing in court.

-

Testimony from enslaved individuals against white citizens was generally inadmissible.

-

Children inherited the legal status of their mothers, regardless of paternity.

This legal framework created conditions in which abuse could occur without formal consequences, even when patterns were widely suspected.

A Pattern That Could Not Be Publicly Named

According to the recovered documents, at least twenty children were born over a five-year period on several plantations within a relatively small geographic area. Observers at the time noted that these children shared distinctive features not typical of their mothers or the enslaved community around them.

The records did not frame this as a criminal matter—because under the law, it could not be one. Instead, the author of the notes, a white landowner troubled by what he observed, attempted to document dates, locations, and movements of individuals who had access across multiple plantations.

What makes the material historically significant is not the claim of abuse alone—historians already acknowledge that sexual exploitation was widespread under slavery—but the systematic documentation of repeated incidents connected to one individual with social and legal protection.

Why the Law Offered No Remedy

From a modern perspective, it can be difficult to understand why such evidence did not lead to prosecution. The reason lies in how antebellum law defined rights and harm.

Under Virginia statutes of the 1840s:

-

Harm was recognized primarily as damage to property.

-

Sexual exploitation of enslaved women was not legally categorized as a crime against the victim.

-

Plantation owners could pursue civil complaints only if they believed their “property” had been damaged by another owner, not if the owner himself was responsible.

As one later governor reportedly acknowledged when shown similar evidence, the law was “functioning as designed.” It protected the existing social order rather than individual dignity.

Attempts to Preserve a Record

The individual who compiled the strongbox materials appears to have understood that no immediate justice was possible. Instead, his goal was preservation. The documents include dated notes, summaries of conversations, and early photographic images—then a relatively new technology—suggesting an awareness that future generations might judge the events differently.

Decades later, after the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery, these records remained hidden. They were passed down privately and never entered official archives, likely because they implicated prominent families and challenged long-standing narratives about plantation life.

Scholarly Review in the Twentieth Century

When the materials resurfaced in the 1970s, historians undertook a careful verification process. Plantation ledgers, census data, and land records were cross-checked against the notes in the strongbox. While some details could not be independently confirmed, the overall pattern aligned with what is known from broader scholarship on slavery and coercion.

An academic article published in the mid-1970s presented the findings cautiously, emphasizing that the case illustrated structural abuse, not an isolated anomaly. Reactions were mixed. Some scholars praised the work for grounding discussions of exploitation in primary sources. Others warned against drawing broad conclusions from a single documented pattern.

What Happened to the Children

Tracing the later lives of the children mentioned in the records proved difficult. Sale documents suggest that many were transferred to other regions as they grew older, a common practice that fragmented families and erased personal histories. In a few cases, descendants were identified generations later through genealogical research.

For those families, learning the documented history was complex. Some expressed relief that long-held family stories now had context. Others felt ambivalence about reopening painful chapters of the past.

Why This History Matters Today

The significance of the “emerald-eyed children” records lies not in their uniqueness, but in their clarity. They demonstrate how:

-

Legal systems can normalize harm by refusing to recognize victims.

-

Power structures shape which truths are recorded and which are silenced.

-

Documentation, even when ignored for generations, can challenge inherited narratives.

Modern historians view the case as a reminder that slavery was sustained not only through forced labor but also through control over bodies, families, and reproduction.

Remembering Without Sensationalism

It is important to approach such histories with care. The goal is not to shock, but to understand how law, economics, and social hierarchy interacted to produce lasting trauma. The people involved—especially the women whose lives were constrained by the system—rarely left written records of their own. What survives comes filtered through observers who had the privilege to write and preserve documents.

Acknowledging that imbalance is part of responsible historical study.

Conclusion

The rediscovery of records detailing a group of children born under similar circumstances in antebellum Virginia does not reveal a hidden anomaly; it illuminates a known reality made visible through documentation. Slavery’s legal framework created conditions where exploitation could be repeated, observed, and yet officially denied.

By studying such cases today, historians and readers alike gain a clearer understanding of how injustice can be embedded in law—and why preserving evidence, even when it seems powerless at the time, can matter generations later.

Sources

Journal of Southern History – archival analysis of antebellum Virginia records

Library of Virginia – plantation and county documentation

University of Virginia historical research publications

Secondary scholarship on slavery and reproductive coercion in the American South