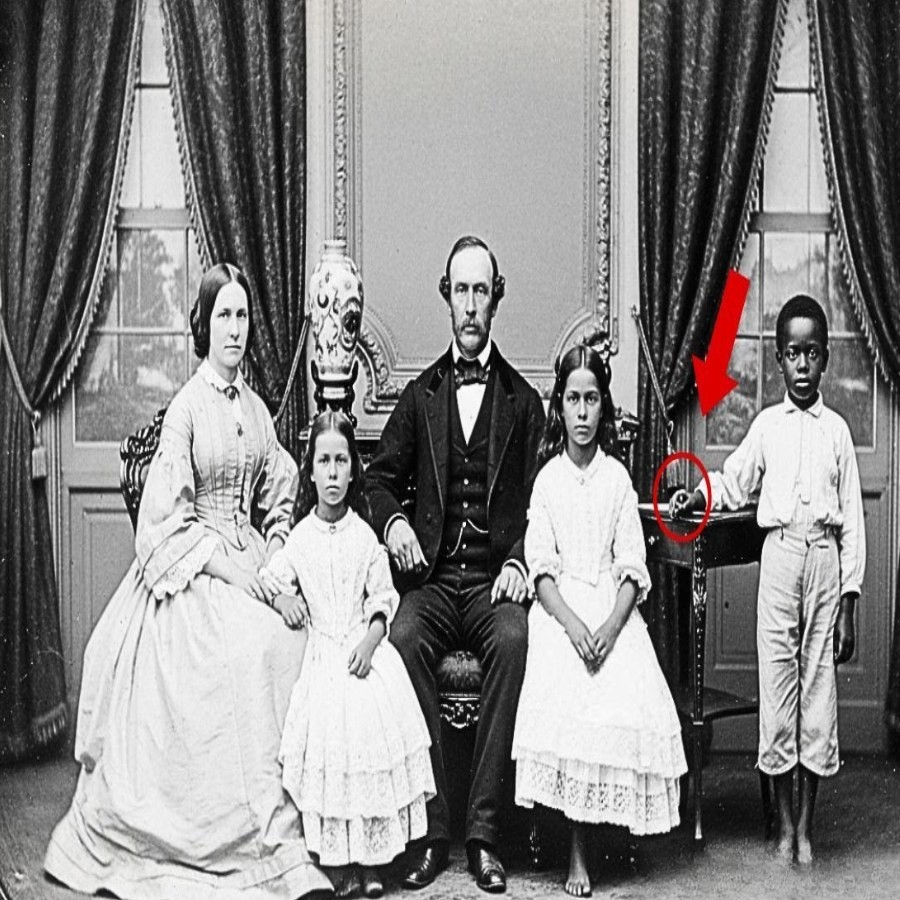

A Portrait That Seemed Ordinary at First Glance

In early 2024, while cataloging nineteenth-century photographic collections, a historian encountered an image that initially appeared unremarkable. The photograph dated to 1856, a formal family portrait from Richmond, Virginia, captured in the stiff, carefully arranged style typical of early photography.

The setting was refined and deliberate. A white family stood at the center, dressed in formal clothing that signaled wealth and social standing. Heavy curtains, polished furniture, and ornate décor framed the scene. To the side stood a young Black child, barefoot and dressed simply, positioned as part of the household rather than as a family member.

At first glance, the photograph reflected a familiar and unsettling reality of the antebellum South: enslaved children presented as symbols of status. But closer inspection revealed something unexpected—something that transformed the image from a record of power into a quiet testimony of resistance.

A Detail Hidden in Plain Sight

High-resolution scanning revealed extraordinary clarity. When the historian enlarged the image, focusing on the child’s hands, a small object emerged—nearly invisible in the original print. Between the boy’s fingers was a narrow piece of metal, deliberately concealed yet firmly held.

The object was a key.

Not decorative. Not symbolic in a modern sense. A real key, consistent in size and shape with those used for locks and restraints in the mid-nineteenth century. The discovery raised immediate questions. Why would a seven-year-old child be holding such an object during a formal portrait? How had it escaped notice by the adults arranging the scene?

The photograph, once silent, now demanded interpretation.

Identifying the Child

Archival records associated with the image identified the child as Benjamin, an enslaved boy listed as a household servant. Ledgers described him with the same detached language applied to furniture or livestock, offering age and function but no narrative.

Further research revealed that Benjamin’s father had died two years earlier under circumstances vaguely described as “disciplinary.” His mother remained enslaved in the same household, working as a cook.

Personal correspondence from the family mentioned concerns about Benjamin’s “defiant temperament” following his father’s death. Such language, common in records of the time, often signaled grief, resistance, or fear—emotions enslaved children were never permitted to express openly.

Context Beyond the Image

Household inventories from the same year documented iron restraints stored on the property. Keys to these locks were controlled tightly, their absence considered a serious breach. The presence of a key in Benjamin’s hand, therefore, was not accidental or harmless.

Letters written shortly before the photograph referenced unrest within the household and anxiety over “outside influences” among enslaved workers. The language suggested fear—not of disorder, but of organized resistance.

The photograph had been taken during a period of heightened tension, and Benjamin’s act of concealment occurred within that fragile moment.

What the Key Represented

Additional documents uncovered the likely purpose of the key. It had been stolen from storage and used to unlock restraints intended for people attempting to flee enslavement. Records confirmed that two individuals escaped during that same period, though the details were deliberately obscured.

Benjamin’s role was never publicly acknowledged. Instead, within weeks of the photograph, records noted that he was removed from the household and sold to a distant plantation in Louisiana.

The punishment was severe and intentional. Selling enslaved children “south” was a known tactic used to destroy family bonds and discourage resistance. Separation was the enforcement mechanism of control.

Tracing Benjamin’s Fate

Plantation sale records from New Orleans confirmed the transfer. Benjamin was listed as healthy, young, and valuable—language that stripped his experience of any human context. Within months, however, he was sold again.

This second transaction was unusual. The buyer was a free woman of color, known through surviving correspondence to have quietly purchased enslaved children to protect them from harsher conditions. Letters between her and contacts in Virginia indicated that Benjamin’s mother had reached out through a network that connected free Black communities across state lines.

The network functioned through coded language, shared trust, and extraordinary risk.

Benjamin had not been abandoned.

Survival and Education

Records from New Orleans reveal that Benjamin remained in the woman’s household, receiving education and protection rather than plantation labor. He learned to read and write at a time when literacy among enslaved people was criminalized.

When Union forces reached New Orleans during the Civil War, Benjamin was formally emancipated, though he had effectively lived as free for years. Still a teenager, he began assisting in schools for formerly enslaved people, teaching basic literacy and arithmetic.

Education became his calling, not as abstraction, but as survival.

Reuniting Mother and Son

After the war, emancipation records show Benjamin’s mother actively searching for him through federal agencies created to reunite families separated by slavery. Letters confirm that they were reunited in 1865, nine years after their forced separation.

Their reunion was not quiet or private. Church records describe it as a moment of communal celebration, evidence that resistance had endured.

Mother and son worked together during Reconstruction, teaching literacy and vocational skills. Their names appear in meeting minutes of early civil rights organizations advocating voting rights and public education.

The Key as a Lifelong Symbol

Benjamin kept the key for the rest of his life.

Later accounts from students described him carrying it in a small box on his desk. He used it not as spectacle, but as lesson. The object reminded him—and those he taught—that freedom was not abstract. It was built through action, knowledge, and courage, even when the cost was unbearable.

He became a respected educator, author, and community leader, contributing to schools and public life well into the early twentieth century.

A Legacy Passed Down

Generations later, Benjamin’s descendants continued his work. Teachers, principals, and advocates traced their commitment to education back to the stories passed down within the family.

The key itself survived.

Preserved quietly for decades, it was eventually recognized for what it represented—not merely an artifact, but proof that resistance existed even in moments designed to erase it.

When historians matched the physical key to the photograph, the story came full circle.

Reinterpreting the Photograph

Displayed in modern exhibitions, the portrait now carries layered meaning. What once appeared to be an image of control has become evidence of defiance. The child’s rigid posture, once assumed to reflect submission, now reads as discipline under pressure.

The key, barely visible, reframes the entire composition.

It reveals that the photograph did not capture a moment of stillness, but one of immense risk. A child stood motionless for an extended exposure, concealing an object that symbolized freedom, knowing discovery could cost everything.

Why This Story Matters Now

This discovery has reshaped how historians approach similar images. Early photographs were often staged to present slavery as orderly and unchallenged. But when examined closely, they sometimes contain subtle traces of resistance—objects held, clothing worn, postures assumed.

Benjamin’s story encourages viewers to look again, not only at photographs, but at narratives long considered settled.

History is not only what was intended to be shown. It is also what people managed to hide in plain sight.

The Quiet Power of Resistance

Benjamin was seven years old.

He did not lead armies or write laws. He stole a key. He used it. He accepted the consequences. And he survived long enough to turn that act into a lifetime of teaching and community building.

The photograph from 1856 was meant to preserve the authority of those who enslaved him. Instead, it preserved his courage.

Today, the image stands as a reminder that even under systems designed to erase agency, people found ways to act. Sometimes resistance was loud. Sometimes it fit into the palm of a child’s hand.

And sometimes, it waited more than a century to be seen.